The startup using balloons to cool the planet

- Since the Industrial Revolution, released greenhouse gasses have increased Earth’s average temperature by trapping solar energy.

- One potential intervention, stratospheric aerosol injection, posits that we can reflect some solar energy into space using aerosols sprayed into the atmosphere.

- The idea has risks and controversies, but some entrepreneurs are already trying it.

This article is an installment of Future Explored, Freethink’s weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Saturday morning by subscribing above.

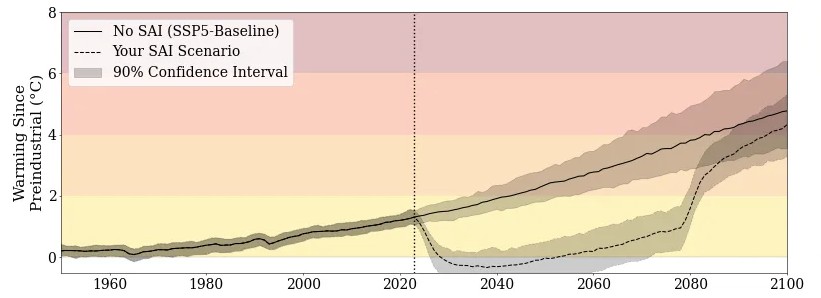

It’s 2050, and for the first time in 100 years, the average global temperature actually went down during the last decade. In this future, the abrupt reversal of global warming is due to a massive solar geoengineering initiative that’s making Earth’s atmosphere more reflective — buying us time to finish the transition to a fully carbon-neutral society.

Solar geoengineering

Earth’s atmosphere contains carbon dioxide, methane, and other “greenhouse gasses.” These trap some of the solar energy that reflects off Earth’s surface, preventing it from continuing on into space, which helps our planet maintain its temperature.

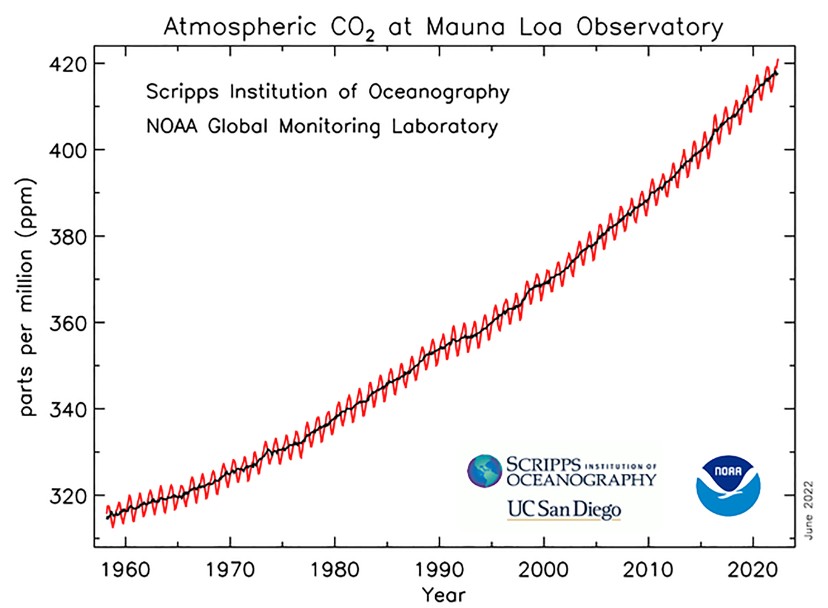

Human activity since the Industrial Revolution — accelerating in the latter half of the 20th century — has dramatically increased the amount of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere. That is trapping more solar energy than normal, which is leading to global warming.

The only long-term solution is to stabilize greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere, but transitioning away from fossil fuels is a slow and costly process, and countries are currently not close to being on track to prevent further significant warming. To cool the planet in the meantime, some people think we should try to reflect some solar energy back into space, using aerosols sprayed into the atmosphere.

To find out whether this intervention, known as stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI), is a viable weapon in the battle against global warming, let’s take a look back at its history, the arguments that it would be a huge mistake, and the startup putting it into action right now.

Where we’ve been

Where we’re going (maybe)

In the more than 50 years since the White House’s Science Advisory Committee first floated the idea of combating the effects of climate change with solar radiation management (SRM), aka “solar geoengineering,” the problem of global warming has only gotten worse.

The 2010s were the hottest decade on record, and climate experts say we now need to not only radically reduce our emissions but also remove some of the carbon we’ve already released to avoid the worst predicted effects of climate change — and we’re not doing either quickly enough.

It was against this backdrop that entrepreneur Luke Iseman first came across the concept of SAI in a science-fiction book. Intrigued, he started reading everything he could find on the topic and talking to experts in the field, but his research just left him frustrated.

“I was like, ‘Why has no one done this? What am I missing here?’” he told Freethink. “No intellectually honest person debates whether climate change is real, yet we have this super powerful tool, and no one has even done a small research release of the particles.”

So he decided to be the one to do it: “I bought a couple hundred dollars of balloons on Amazon, a tank of helium, and some sulfur powder, and we were off to the races.”

Make Sunsets

Today, Iseman and fellow entrepreneur Andrew Song are the co-founders of Make Sunsets, a startup that is actually deploying reflective particles into Earth’s stratosphere in an effort to combat global warming.

It does this by filling biodegradable latex balloons with a mix of sulfur dioxide (SO2) and helium or hydrogen gas before releasing them. As the balloons rise, the decreasing air pressure causes them to expand until they burst, releasing their sunlight-reflecting payloads.

Make Sunsets attaches cameras and sensors to each balloon so that it can verify that it reached the stratosphere before bursting. That also allows them to locate the popped balloon for retrieval after landing, which usually happens about 3-5 hours after launch.

“I will always shout out Make Sunsets because they’ve gone out and tried the crazy thing.”

Casey Handmer

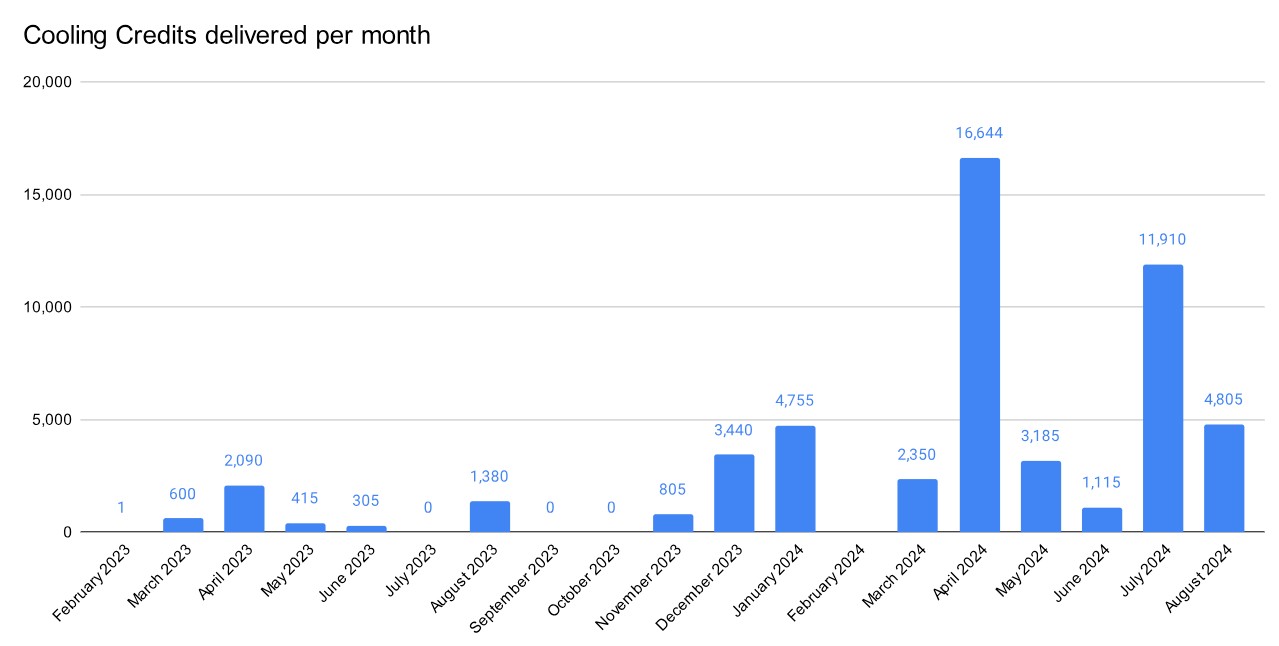

Make Sunsets is currently backed by venture capital, and the path to profitability centers on selling “Cooling Credits” to people or companies interested in offsetting the warming effect of their carbon emissions.

Each $10 credit pays for the release of 1 gram of SO2 into the stratosphere, which the startup calculates is enough to offset the warming effect of 1 ton of CO2 for 1 year (the average American generates about 16 tons of CO2 per year). The cost drops with a commitment to buy more credits.

At the time of writing, Make Sunsets has deployed 82 balloons, offsetting the warming caused by 53,800 tons of CO2 (the world emits about 37 billion tons of CO2 annually). It has more than 500 customers, including Casey Handmer, founder and CEO of Terraform Industries, a startup using tech to create natural gas from sunlight and air.

“I will always shout out Make Sunsets because they’ve gone out and tried the crazy thing and they’re doing it,” Handmer told Freethink. “I’m one of their earliest customers and one of their proudest customers.”

“I think that we should definitely be doing this at large scale,” he added. “I know I’m one of the more strident voices on this, but I will speak my truth.”

The controversy

While Handmer believes the world should be scaling up SAI to the level that it could have a significant impact on global temperatures, others worry that injecting enough particles into the stratosphere to cool Earth could have myriad negative consequences — it might deplete the ozone layer, for example, or alter precipitation patterns in ways that affect crop yields.

Any particles released into the stratosphere would only remain there for a year or two before falling back to Earth, too, which makes its cooling effect short-term while the side effects may be more persistent.

And that brings up another concern about SAI: Because the effect is temporary, stopping a major initiative could cause temperatures to rise quickly, aka “termination shock” (also the title of the Neal Stephenson sci-fi book that inspired Iseman to learn about SAI in the first place).

To avoid that, we would need to be extremely cautious if we wanted to attempt SAI on a large scale, with a plan in place to replenish the stratosphere’s aerosol levels indefinitely or at least until we figured out some other way to unwind it or prevent temperatures from suddenly rebounding.

The good news is that, from a monetary standpoint, continuous deployment is something we could probably do.

In 2018, Harvard researchers calculated that an SAI program designed to reduce global temperatures by 1.5 C within 15 years would cost $2-$2.5 billion per year. For context, the US federal government budgeted $12 billion just for clean energy innovation in 2023.

“Given the potential benefits of halving average projected temperature increases from a particular date onward, these numbers invoke the ‘incredible economics’ of solar geoengineering,” said Gernot Wagner, co-author of the Harvard study. “Dozens of countries could fund such a program, and the required technology is not particularly exotic.”

“Such dangerous planetary-scale interventions cannot be governed in a globally inclusive, fair, and effective manner.”

Open letter against solar geoengineering

Even if SAI were free, though, some people believe it’s unethical to even contemplate it given that it would affect the entire world, and there’s no chance we could ever get everyone to agree to it.

“Such dangerous planetary-scale interventions cannot be governed in a globally inclusive, fair, and effective manner and must be banned,” reads an open letter against SAI and other forms of solar geoengineering that has been signed by more than 500 scholars since 2022.

The authors of that letter also argue that even talking about solar geoengineering as a viable weapon against climate change could be enough to disincentivize some from taking action to reduce emissions — something that would reduce the underlying driver of global warming.

“The speculative possibility of future solar geoengineering risks becoming a powerful argument for industry lobbyists, climate denialists, and some governments to delay decarbonization policies,” they write.

The big picture

So, SAI is a relatively affordable climate change intervention that evidence suggests would reduce global temperatures — but it could also mess with the ozone, affect food production, increase air pollution, and cause other unforeseen problems.

Oh, and to implement it, we would need to deliberately mess with the climates of likely billions of people without their permission, which is arguably unethical and could lead to more conflict.

It’s not hard to understand why the intervention is so controversial, but at the same time, we’re already seeing evidence of what the future will look like if we don’t stop global warming: worsening extreme weather, food insecurity, habitat loss, and economic instability.

So, yes, implementing SAI would be risky, but there could come a point soon when not implementing it is even riskier, and some governments are likely going to consider doing it — we need to be much better informed about the full range of costs and benefits in case that day comes, which is why many scientists are now calling for more research into solar geoengineering.

“AI-based climate modeling is an especially promising direction for answering many of the open questions [about SAI].”

Andrew Ng

The UK’s Advanced Research and Invention Agency recently announced $75 million in funding for climate cooling research, and in 2023, more than 100 climate scientists signed an open letter arguing for “a rigorous, rapid scientific assessment” into SAI and other forms of SRM, like marine cloud brightening and cirrus cloud thinning.

Machine learning pioneer Andrew Ng has also voiced his support for studying solar geoengineering.

“I think SAI is a promising technology, but we still need more research into it to better understand its impact, and AI-based climate modeling is an especially promising direction for answering many of the open questions,” he tweeted in June 2024.

To get more people thinking about SAI and inspire more AI research into it, Ng’s research team recently released a free AI-based climate emulator called Planet Parasol. The tool is basic, but anyone can use it to see how different SAI interventions might affect global temperatures.

“Despite its potential, research on SAI has been stigmatized largely due to fears surrounding other impacts of such an intervention,” co-developer Jeremy Irvin told Freethink. “However, we believe conducting research on SAI now is crucial to provide future decision-makers with more comprehensive information as they consider deploying SAI for short-term temperature reduction.”

While more lab research and better climate models might be able to improve our predictions of what’ll happen if we inject enough particles into the stratosphere to significantly cool Earth, there’s no arguing that, at some point, we will need to actually perform outdoor experiments, at least on a small scale.

“We will have to go outside eventually,” Matthew Watson, lead researcher on the University of Bristol’s canceled Stratospheric Particle Injection for Climate Engineering (SPICE) project, told the Guardian in 2014. “There are just some things you cannot do in the lab.”

Whether now is the right time is debatable, but Make Sunsets is doing it anyway, and, unfortunately, they are not climate scientists, nor are they equipped to do the kind of research that might allow us to optimize the cooling impact of SAI while minimizing the chances of unwanted effects.

“Startups fighting to be the lowest cost way to have a down button on the global thermostat is a hell of a lot better than doing nothing.”

Luke Iseman

Thankfully, the amount of SO2 Make Sunsets is injecting into the stratosphere right now is too little to raise concerns about triggering any of SAI’s potential side effects, and Iseman has said the startup will hire scientists if it scales up.

He is cautiously optimistic that Make Sunsets will reach profitability before the end of 2024, which he says will allow the startup to “keep going forever,” but he’s also hopeful that the private sector won’t be alone in actually getting out and “trying the crazy thing” for long.

“I hope that we don’t have to just rely on startups to do [SAI] — we’re not the ideal mode of delivering public goods, and dropping global temperatures is pretty much the definition of a large-scale public good,” Iseman told Freethink.

“That said, startups fighting to be the lowest cost way to have a down button on the global thermostat is a hell of a lot better than doing nothing,” he continued.

This article was originally published by our sister site, Freethink.