Here’s what being filthy rich in China looked like in 1, 1000, and 2000 AD

- China during the Han dynasty was a hierarchical society in which wealth was reserved for the nobility.

- The Song dynasty saw the rise of an upper-middle class that enjoyed social clubs and exotic food.

- Today’s China is one of the richest places in the world, but the Chinese Communist Party isn’t necessarily happy for people to flaunt it.

For most of human history, China has been one of the wealthiest countries in the world. When Marco Polo visited the Yuan dynasty in the late 13th century, he was impressed by its military strength, social structure, and — above all — its obscene wealth. Traveling down the Jinghang Waterway, which to this day remains the longest canal on Earth, he found no shortage of “very great merchants” that sold “silk beyond measure” and “the most beautiful vessels of porcelain large and small.”

Each city the Venetian merchant entered was more remarkable than the last. Fuzhou, in Fujian Province, was a “center of commerce in pearls and precious stones (…) so well provided with every amenity that it is a veritable marvel,” while nearby Quanzhou was “one of the two ports in the world with the biggest flow of merchandise.” His personal favorite was Hangzhou, which he labeled “the greatest city which may be found in this world.” At the time of Polo’s visit, it already counted 1.5 million inhabitants. His native Venice, by comparison, had only around 70,000.

Of course, the Chinese economy has had its downturns as well, especially in the last few centuries. Think of Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward. This cultural and financial campaign, which ran from 1958 to 1962, saw the Communist Party attempting to turn China’s largely agrarian society into a fully industrialized one capable of rivaling the nations of Western Europe and the United States. Farmers were collectivized and factories appeared from nowhere. But while the agricultural sector shrank, so did food supplies, causing shortages that killed tens of millions of Chinese citizens or possibly even more.

Recently, memories of the Great Leap Forward have been offset by the results of vastly different and more fruitful economic policies. Gradually opening the country up to private enterprise, Mao’s successors managed to strike a careful balance between communism and capitalism which resulted in sustained economic growth. Between 2010 and 2022, China’s GDP more than doubled, overtaking that of the U.S. With a change in GDP came a change in living standards. That said, modern China’s upper class lives completely differently from the upper class of Yuan China, just as it lived differently compared to the dynasties that came before.

1 AD: Han dynasty

China’s Han dynasty was founded in 206 BC by Liu Bang, a peasant who worked his way up to law enforcement officer in the Qin Dynasty and, once the Qin started crumbling, revolutionary. Despite its rocky start, the Han dynasty proved to be one of the longest and most stable in Chinese history, bringing population growth, urbanization, and scientific inventions like the seismograph — developments that were made possible by Han economic policy, which laid the foundation for the Silk Road and the opulence encountered by Marco Polo a millennium later.

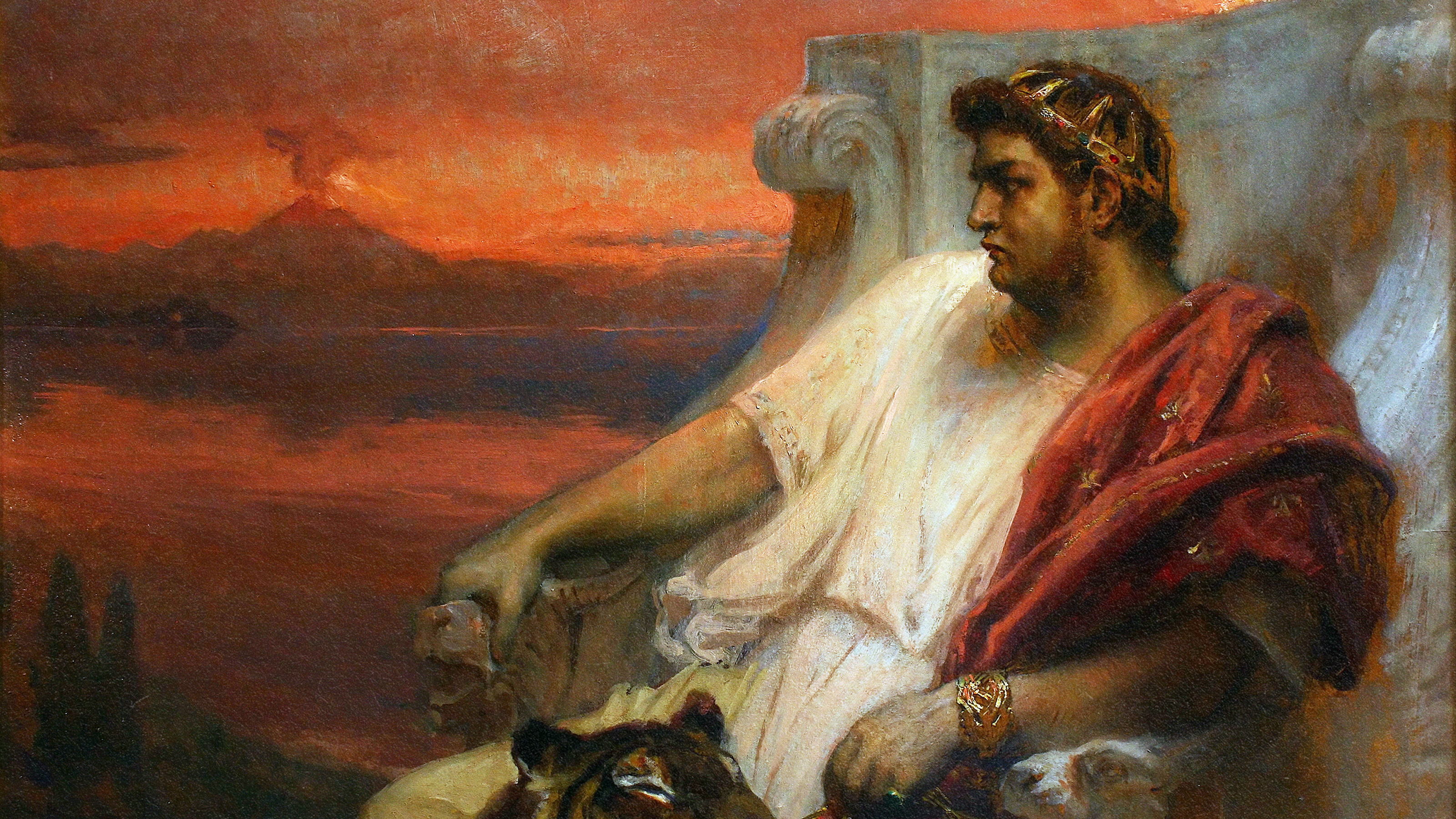

Han dynasty China was hierarchical, with the emperor presiding over affluent and influential families who in turn presided over a working class of free peasants who gave up parts of their harvest as taxes. It was a system the Han had inherited from the Qin, but which became more stratified under their rule. The nobility were given titles such as “hou,” comparable to the European “marquis.” They owned land, managed peasants, provided armies, and assisted the emperor in his many centralized responsibilities, including the coordination of Han China’s biggest markets: salt and silk.

While we don’t have many written sources from this period detailing the daily lives of people from different classes, artifacts offer a glimpse into what it was like to be rich under the Han. Elites owned a variety of finely crafted animal masks, which they used to decorate everything from doors to coffins. Belief in the afterlife was strong during the Han dynasty, and people of note were entombed with legions of terracotta soldiers and piles of jade. Jade, then more valuable than gold, was also fashioned into containers to store fermented grain and rice wines — delicacies that remain popular in China today.

Although the Han emperors held near-absolute power and personally controlled many aspects of society, their private lives — while relatively luxurious and comfortable — weren’t always as lavish as you might think. At least, this was the example set by Wen-di, the dynasty’s fifth ruler, who reigned from 180 BC until his death in 157 BC. Wen-di is thought to have worn robes of coarse silk that were designed in the same style as those of his consorts and continuously turned down proposals to enlarge the already imposing imperial palace. He reduced the size of the imperial retinue, insisted on being buried without precious metals, and was remembered for forgiving tax debts in times of need.

1000 AD: Song dynasty

The Song dynasty was founded by Zhao Kuangyin, a general who, according to legend, was so popular with his troops that they convinced him to overthrow the sitting emperor and claim the throne for himself. His new government, which remained in place from 960 AD to 1279 AD, reunited China’s Ten Kingdoms into a single entity. Reunification enabled economic reform, with the Song dynasty moving away from the top-down command economy of the preceding Tang period in favor of free markets. Under Song management, China grew three times richer than 12th-century Europe.

Chinese historians look back on the Tang-Song transition and the Song economic revolution as a defining moment in China’s past. Rice production in the Yangzi River Valley overtook conventional agriculture in the Central Plain to become the engine of the Chinese economy, while Confucianism returned to replace Buddhism as the official religion. Land ownership, state-controlled in the days of the Han, became privatized, and the Song adopted a progressive taxation system to balance out the rural poor and urban rich, allowing the former to acquire and invest capital of their own.

Emperor Shenzong, the dynasty’s sixth emperor, was the polar opposite of Wen-di. Ruling from 1067 until his death in 1085 AD, he was one of the wealthiest rulers of all time, giving the African king Mansa Musa a run for his money. With an estimated wealth equivalent to roughly $30 trillion, Shenzong’s lavish spending habits set the standard for China’s elite, who spent much of their free time at social clubs. One 1235 text mentions, among others, the West Lake Poetry Club, the Buddhist Tea Society, the Horse-Lover’s Club, and the Physical Fitness Club, and the Plants and Fruits Club.

This assortment in pastime was rivaled only by the variety of food and drink. Prior to the cultivation of the Yangzi River Valley, the Chinese mainly ate wheat and drank wine. Aside from rice and tea — Chinese staples that originated under the Song — the upper classes snacked on a variety of exotic dishes, including a 100-flavors soup, milk-steamed lamb, and oven-strewn hare. Previously scarce food items became so popular and readily available that Chinese chefs started serving “imitation dishes” for people who didn’t wish to eat a particular animal but still enjoyed the dishes that were made with them.

2000 AD: People’s Republic

The PRC’s economic boom, which reached its zenith between 1990 and 2004, when the Chinese economy grew at a record-breaking average of 10% per year, began on December 18, 1987, when followers of Chairman Deng Xiaoping decided to do something Mao would never have allowed. Announcing a series of reforms under the motto “Reform and Opening-up,” they reversed agricultural collectivization and transitioned — as the Song had done before — from a top-down command economy to a free market. (Well, not entirely free, but freer than it had been since the communists took over.)

In only a couple of decades, Chinese society changed beyond recognition. Household spending on food went down while spending on luxury goods increased, reviving the country’s long-lost tradition of frequent gift-giving. Urban workers left their government positions to try their luck at entrepreneurship. Studies show that, as people started running their own businesses and became responsible for their own financial successes and failures, productivity increased — a trend that continues to this day, with many middle- and upper-middle-class citizens working a so-called 996 schedule: 9:00 am to 9:00 pm, six days per week.

Because the Chinese government spent such a long time persecuting wealth and redistributing income, it should come as no surprise that the country’s contemporary elite want to enjoy and display their fortunes, just like their Western counterparts do. Walking through the best neighborhoods of Beijing and Shanghai, it’s no longer unthinkable to see people driving around in expensive cars, wearing Rolexes, or sending off their children to expensive foreign schools. China is now one of the biggest markets for private planes and yachts, with the number of docked luxury vessels rising from 1,000 in 2010 to 100,000 in 2020.

But while China’s workers are getting richer, the state remains communist. Economic success is a double-edged sword for Chairman Xi Jinping, making the country both more powerful and more difficult to control. In recent years, the Chinese Communist Party has cracked down — if not on wealth, at least on its public display. Censors target social media users posting pictures of expensive meals and clothes, advertisements of luxury products have been banned, and some companies have asked employees to stop flying business class — actions that have motivated many a Chinese billionaire to take up residence abroad.