Doctors needed corpses for dissection. So two men murdered people to provide them

- In 19th-century Scotland, corpses were valuable commodities. They were worth more in winter because they decomposed slower.

- Anatomists like Robert Knox in Edinburgh faced a shortage of bodies for dissections and turned to purchasing corpses from criminal entrepreneurs who robbed graves.

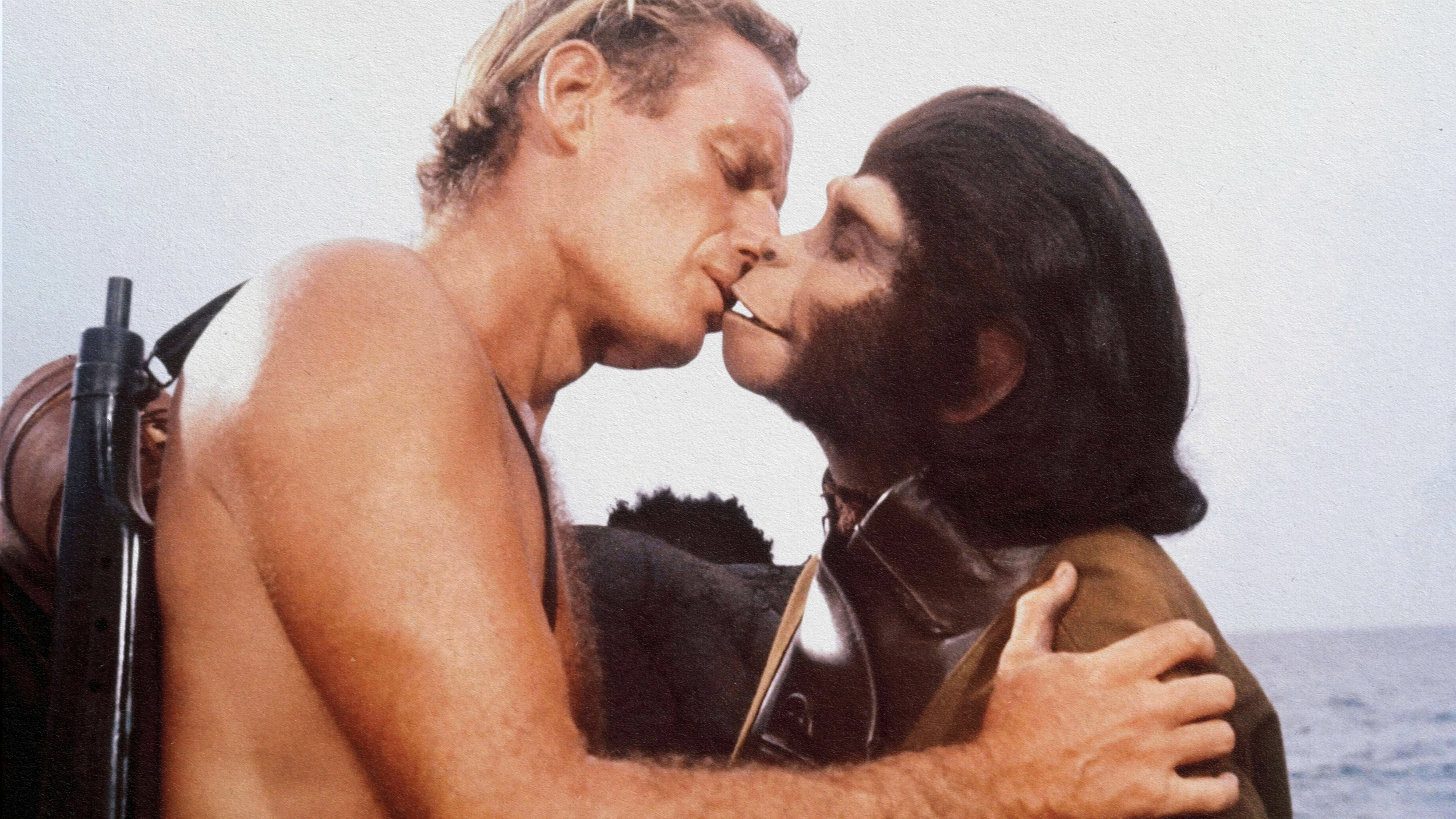

- William Burke and William Hare resorted to murdering people to supply fresh bodies to Knox, eventually leading to their arrest and Burke’s public dissection.

In 19th-century Scotland, a corpse is worth less in summer than in winter. It’s all to do with the rate of decomposition and the quality of the cadaver. If you’re a surgeon at the dawn of physiology, corpses matter. You need a specimen with flesh intact and organs mostly whole. So, in the heady heat of June, you would get $1200 for a body in today’s money. Fresh from the frozen graves of December, you would get closer to $1500. That’s good earning for a body; it would have been several months’ salary for a working man.

In the 1800s, Dr. Robert Knox was doing two public anatomical dissections a day for the people of Edinburgh. He was drawing sellout crowds and developing quite a reputation as well as a bloated bank account. But there was one morgue-sized problem: There weren’t enough bodies to use. Scottish law at the time limited medical dissection to criminals, suicides, or orphans. So, the wily and macabre criminal entrepreneurs of Midlothian would rob graves; they would dig up corpses and sell them on a very black market. For a while, this satisfied the anatomical appetites of unscrupulous surgeons.

By 1827, though, this was no longer so lucrative. First, the 1823 Judgment of Death Act substantially reduced the roll of executable offenses, resulting in fewer hanged bodies. Second, people were getting really annoyed that their dead relatives were being dug up, so the law came down heavily on grave robbing. Finally, people were making it harder. Corpses were locked in iron cages, and guards were placed at graveyard gates. You could even pay to have a huge, multi-ton stone put on your grave until enough time passed for the body to rot away its value.

Into this came William Burke and William Hare.

A spree of drunken murder

Burke and Hare were Irishmen who met while working a harvest outside of Edinburgh. They became notorious for being drunk, bolshy, and antisocial, but they were only ever petty criminals. Burke had a tenant, a man called Old Donald, who had the insolence to die before he could pay his rent. Old Donald owed Burke £4 in back rent, a hefty sum then. When the council delivered a coffin for Old Donald, Burke and his mate Hare cooked up a plan: They stuffed the coffin full of wood chips and hid Old Donald’s corpse under the bed. The councilmen took the coffin without a question, and Burke and Hare whisked their cadaver to Robert Knox. Knox’s assistant, who was not the one to ask questions, paid £8 for the body. As the two Irishmen were going, the assistant remarked that he “would be glad to see them again when they had another to dispose of.”

Old Donald had died from natural causes, but it didn’t take long for a criminal germ to grow into a homicidal business. Why wait for a body to die? Why not speed the process along a bit? Over the course of the next ten months, Burke and Hare murdered dozens of people. They almost always targeted the same kinds of people: drunks, beggars, prostitutes, and travelers who were unlucky enough to be boarding with either Burke or Hare. In other words, they were the forgettable underclass of Victorian Britain, where police wouldn’t bother to investigate. Burke and Hare’s modus operandi was largely the same for each murder. They would get their victim paralytically drunk with whisky and revelry. Then they would suffocate them. Suffocation was the best way to ensure the body remained fresh.

The unscrupulous clients

Every criminal transaction needs a buyer, and in this case, it was the surgeon, Robert Knox. Knox was an old surgeon from the Napoleonic battlefields, but his reputation played second best to that of another Edinburgh anatomist, Alexander Monro. Knox was desperate to prove himself, and his twice-a-day anatomy lessons needed topping up. So, when two Irishmen with remarkably fresh corpses arrived, he wasn’t one to ask questions. A common rhyme was sung at the time: “Burke’s the butcher, Hare’s the thief, and Knox the man who buys the beef.”

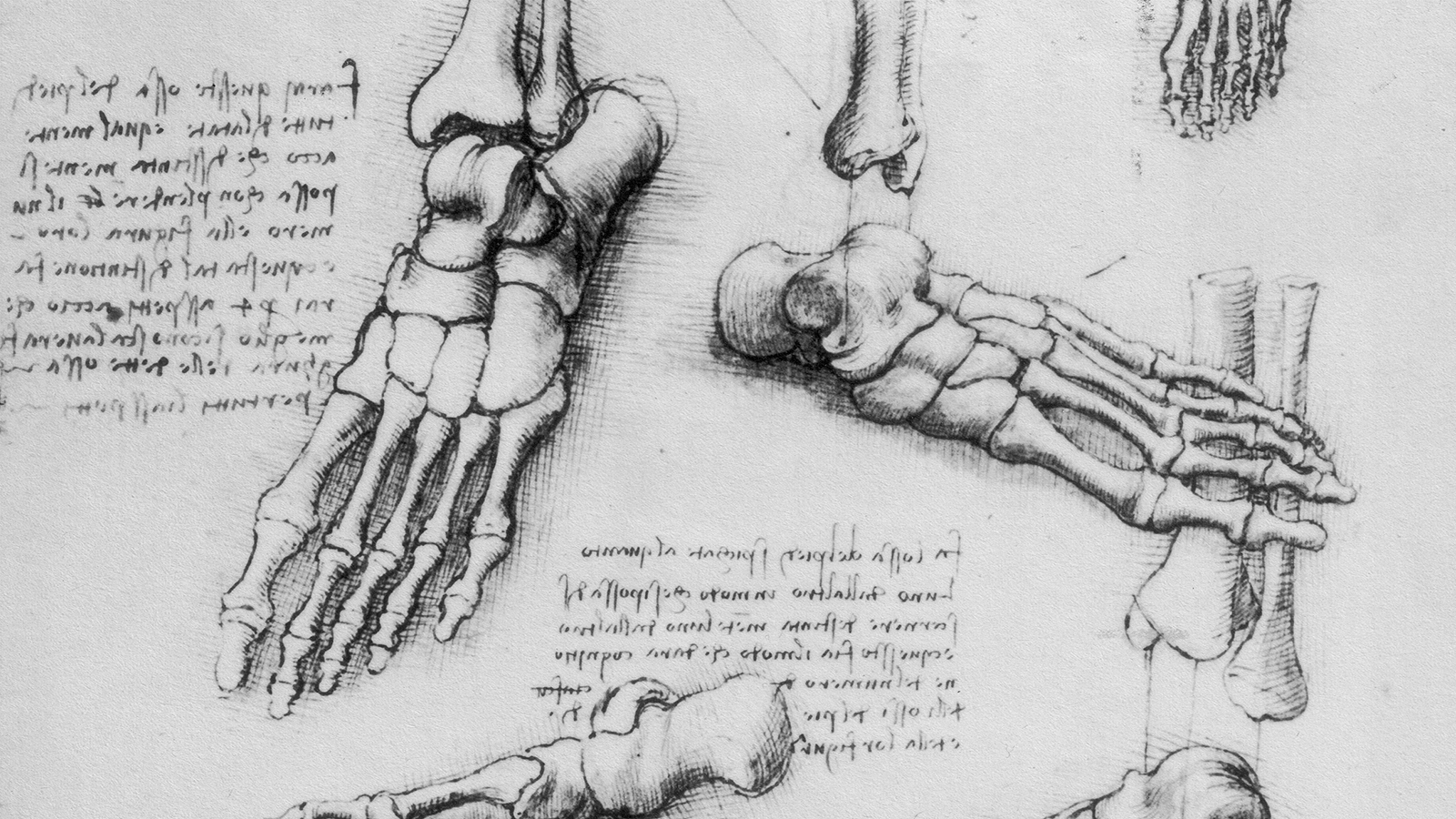

Knox was never arrested in the end, but he must have known. At one time, a grandmother and her grandson were jammed together into a herring barrel and delivered to Knox by a porter. Still, no questions were asked. Then, one victim, Mary Paterson, was still warm when she was delivered. Not only did Knox’s assistant not raise an alarm, he pickled the corpse in a whiskey barrel for three months to avoid suspicion. Finally, when Burke and Hare brought in the freshly murdered body of begging street performer James Wilson, some of Knox’s team recognized him. Wilson had deformed feet and a scarred face. Did Knox call the police? No, he decapitated Wilson’s body and removed his feet before that afternoon’s public dissection. Of course, Knox knew.

A corpse too far

The reason Burke and Hare’s story has appealed so far through the ages is the sheer audacity of the pair. Theirs is a story of classical hubris, where boldness and daring soon spill over into arrogant stupidity. Once, a police constable was walking home with a drunk lady. Burke offered to take her home. The police officer said yes (he must have been very green), and the pair murdered her. Once, Burke’s cousin-in-law came to visit, and they murdered her.

Eventually, their audacity was their undoing. They wanted to murder a new lodger called Margaret Docherty, but had an issue: Two other lodgers, James and Ann Grey, wouldn’t leave for them to get about it. So Burke and Hare paid for the Greys to temporarily move houses so they could kill Docherty. The Greys came back the next day and found the body of Docherty still in their room, buried in straw. Burke and Hare hadn’t even thought to hide the corpse.

The Greys went straight to the police, and the police went straight to Burke’s house. The pair were arrested, but the police found the case hard. All the bodies — and so, all the evidence — were now in the biomedical waste bins of Knox’s basement. So, they got Hare to “turn king’s evidence,” which means he and his wife were offered immunity if he confessed to all the crimes. He did, and Burke was sentenced to be hanged on January 28, 1829.

Gruesomely ever after

While Hare and his wife, as well as Burke’s wife, were not sentenced by the law, they were sentenced by the mob. Crowds followed them around, beating them and threatening vigilante justice until the police locked the three of them up in prison for their own protection. When the mob went home and cooled off, they were all left to flee as they chose. We don’t know entirely where they ended up.

Knox was never arrested, but public opinion turned against him. He was struck off by the Royal College of Surgeons and banned from lecturing. He moved to London, but his notoriety and his crimes followed him southward, and he never recovered his reputation.

As for Burke, at his sentencing, the judge openly told him and the court, “Your body should be publicly dissected and anatomized.” Which is what happened. Alexander Monro, the greatest surgeon in Edinburgh, put on quite a show. He performed the anatomization in a rammed lecture hall and did various macabre flourishes, like dip his quill in Burke’s blood to write a memo. And, if you ever find yourself in Edinburgh, you can still see Burke’s skeleton on display.