Mysterious “population hub” was a starting point for ancient human migration

- Researchers set out to get a clearer picture of how ancient humans migrated into Eurasia.

- They compared the genomes of several ancient colonists and assembled them into a family tree.

- While we now have a better idea of how archaic humans traveled across the globe, the hub location from which they started their journey remains shrouded in mystery.

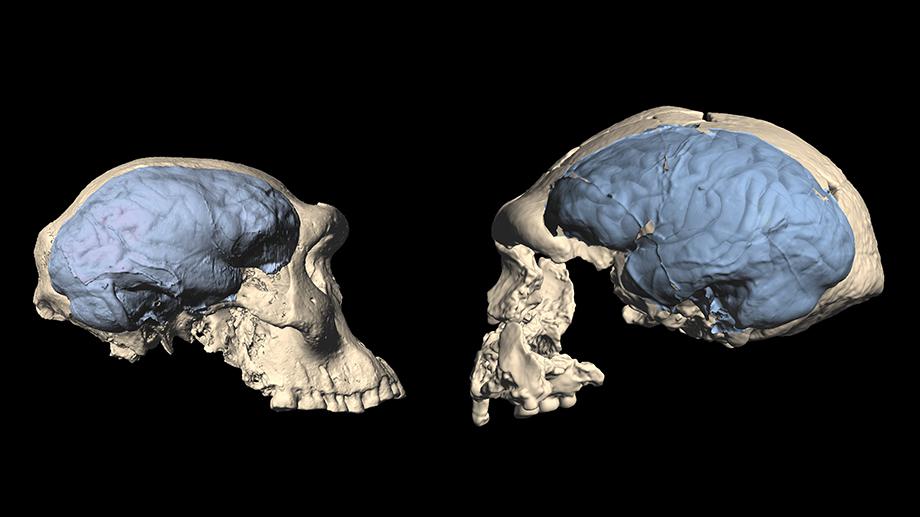

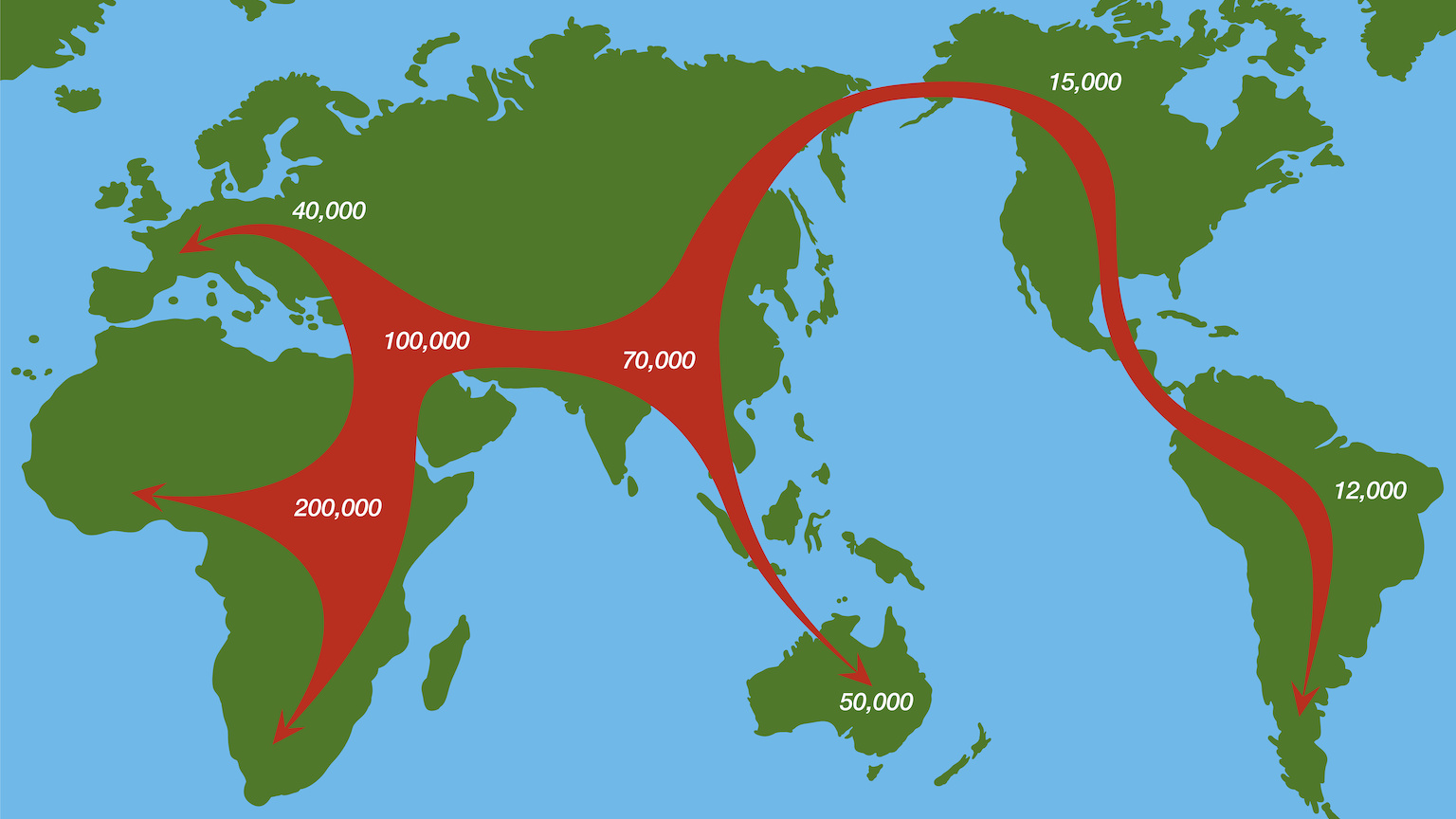

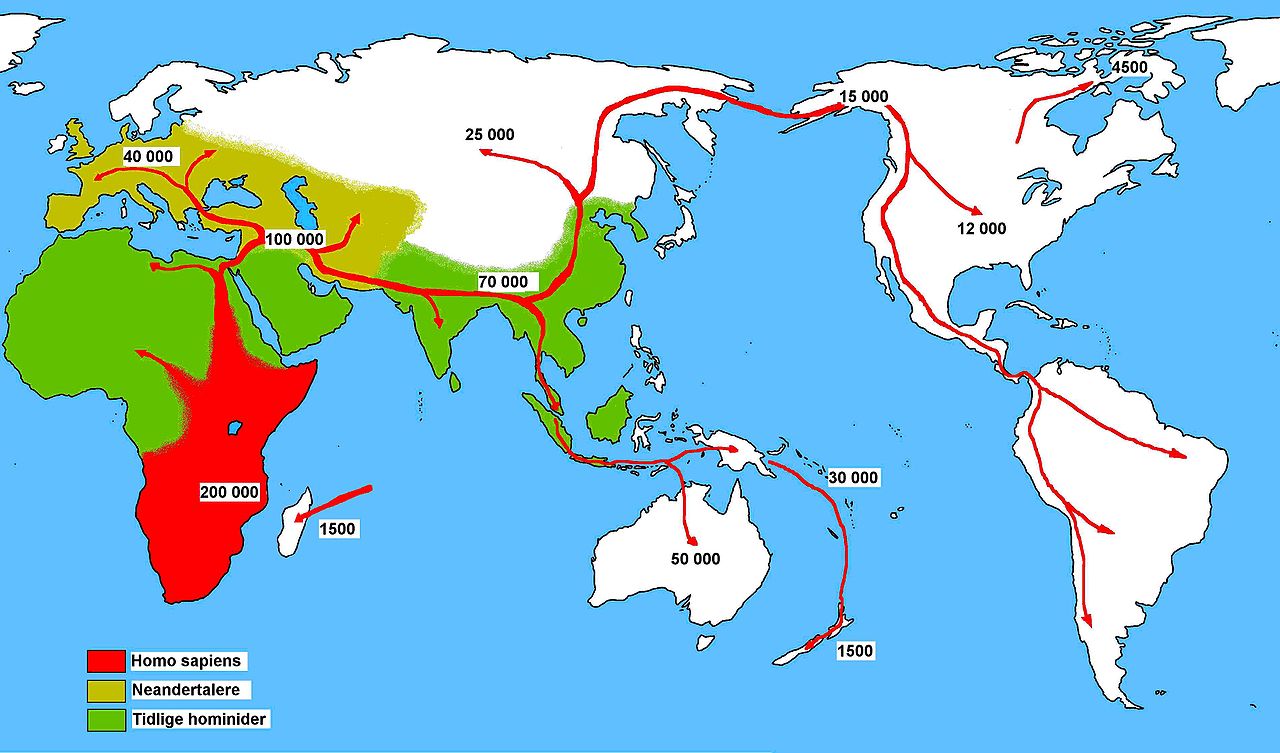

The further back in time you go, the vaguer and more fragmented the fossil record of our ancestors becomes. Hominins, the branch of our family tree that separated itself from the other great apes, are believed to have ventured out of their place of origin in sub-Saharan Africa as early as two million years ago. Members of the now extinct species Homo erectus may have been the world’s first pioneers, followed, 1.5 million years later, by Homo heidelbergensis, a possible ancestor of the Neanderthals.

These hominins got a head start over our own species, Homo sapiens. Fossils from Israel and Greece suggest that their initial attempt to leave Africa happened between 210,000 and 177,000 years ago. This wave of migration ended in failure, with Homo sapiens populations in Eurasia being replaced by Neanderthal communities. Evidence for the interaction and interbreeding between these groups can be found in the DNA of non-African modern humans, less than 4% of which comes from Neanderthals.

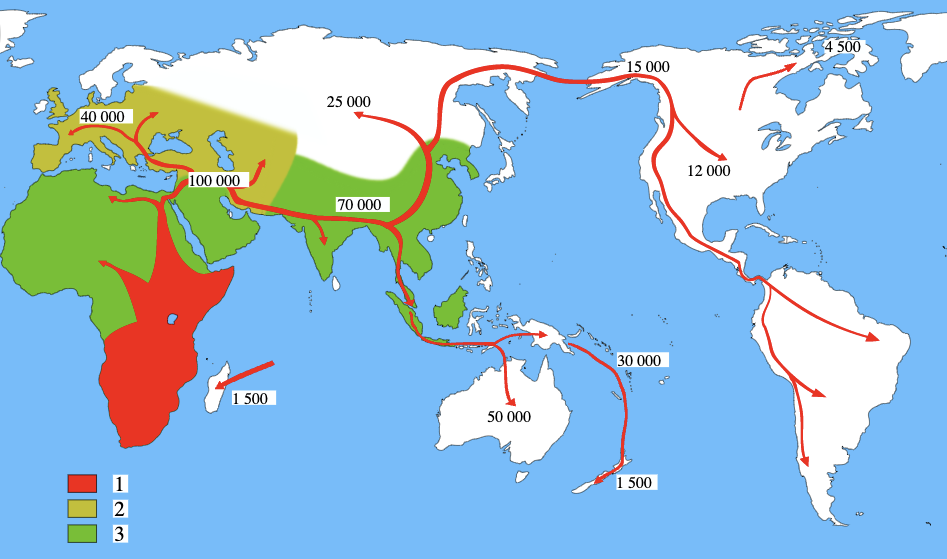

Members of Homo sapiens did not spread across the corners of the globe in a single, uninterrupted migratory movement. Ancient humans undertook dozens of voyages during the prehistoric period, the majority of which were unsuccessful. Sometimes migratory populations were unable to take root in new regions. At other times, they simply packed their things and returned to Africa. A study from last year showed that archaic humans spent almost half a millennium moving in and out of the Arabian Peninsula following changes in the global climate.

Because early migration out of Africa was so inconsistent, we are left with a poor understanding of how ancient humans traveled to and settled across continents. The routes they may have taken to get to Europe, Asia, and the Americas continue to spark fierce debate among researchers, and every few months, a new study places the prevailing argument in a fresh perspective. Recently, geologists from Imperial College London used cosmogenic nuclide exposure dating to rule out the Clovis First hypothesis, which argued humans entered North America via an ice-free corridor in what is modern-day Canada.

Another enduring question of early migration is the way in which our species came to populate Eurasia between 50 and 35 thousand years ago. A group of archaeologists and geneticists from Italy, Germany, and Estonia analyzed paleolithic DNA to better understand the relationships between different migratory groups. Their findings, published in Genome Biology and Evolution, suggest that Homo sapiens settled in a yet to be located “population hub” before “the broader colonization of Eurasia, which was characterized by multiple events of expansion and local extinction.”

Planting a primordial family tree

Fossil evidence shows that archaic humans successfully colonized Eurasia as early as 70 thousand years ago. However, genetic analysis of these fossils reveals eastern and western Eurasian people only began to diverge genetically around 45 to 40 thousand years ago. Many articles have been written to explain what happened during this time gap. The simplest explanation is that eastern and western Eurasian people spent at least 15 thousand years living together at a central population hub before parting ways.

Unfortunately, this explanation does not hold up. In 2021, researchers sequenced genomes from a handful of paleolithic individuals recovered from Bulgaria’s Bacho Kiro cave. The individuals, who lived around 45 thousand years ago, were genetically closer to modern-day East Asians than modern-day Europeans, indicating eastern and western Eurasian populations already diverged once before. The genome of a particularly old paleolithic woman found on Czech Republic’s Zlatý Kůň mountain, meanwhile, differed from both western and eastern Eurasian people.

This is where the article published in Genome Biology and Evolution comes in. “An enhanced understanding of the population dynamics during the broader colonization of Eurasia is critical to explain the shaping of current H. sapiens genetic diversity out of Africa,” its authors explain, “and to understand if cultural change documented in the archaeological record can be attributed to population movements, human interactions, convergence or any intermediate mechanism of biocultural exchange.”

To better understand the role that the aforementioned hub might have played in early migration patterns, the researchers assembled an overview of all the available genomes from archaic humans in Eurasia. They then used genetics software called qpGraph to plot the relationships between individual genomes based on similarities and differences in their DNA. The resulting family tree posits the woman from Zlatý Kůň — the oldest Homo sapiens genome ever sequenced — as “basal to all subsequent splits within Eurasia.”

qpGraph could have processed the data into a number of possible family trees, some of which do not place the woman from Zlatý Kůň at its base. The researchers chose this particular family tree because its organization “matched the spatiotemporal distribution of material cultural evidence at a cross continental scale.” In other words, the relationships depicted in the tree also correspond with similarities between materials such as tools and technology, which, much like DNA, ultimately share common origin.

The peopling of Eurasia as told through DNA

The story told by the article’s family tree goes as follows: The woman from Zlatý Kůň belonged to an early yet unsuccessful expansion into Eurasia that must have taken place sometime before 45 thousand years ago. Genetically, the woman bears little resemblance to modern-day Europeans or East Asians. Because she is the only representative from this migration wave that we have thus far managed to find, it is difficult to say how large this wave was, what parts of Eurasia it reached, or how long it lasted.

“Then, around 45 kya,” study co-author Leonardo Vallini said in a statement, “a new expansion emanated from the Hub and colonized a wide area spanning from Europe to East Asia and Oceania.” The fate of these colonists varied from region to region. While those in Asia who survived became the ancestors of people inhabiting that part of the world today, their European cousins were less fortunate. As evidenced by the bodies from Bulgaria’s Bacho Kiro, settlers of this region gradually vanished.

“Finally,” says co-author Luca Pagani, “one last expansion occurred sometime earlier than 38 kya and re-colonized Europe from the same population Hub, whose location is yet to be clarified.” Genetic analysis shows that the representatives of the second migration wave occasionally interacted with the survivors of the previous one. However, explains Pagani, “extensive and generalized admixture between the two waves only took place in Siberia where it gave rise to a peculiar ancestry known as Ancestral North Eurasian, which eventually contributed to the ancestry of Native Americans.”

In the article, Vallini and Pagani refer to their family tree as a “scaffold that elegantly accommodates available information on the most likely associated cultural assemblies for the most representative ancient human remains available to date.” At the same time, they recognize that their study took on an extremely broad perspective and that more precise research is necessary to test their hypothesis on the branching and adaptation of local populations. Still, their explanation is more comprehensive than the overly simplistic narrative they started out with.

Find the hub

Subsequent studies, the article concludes, should also strive to uncover the location of the fabled population hub that Vallini and Pagani reference but never locate. DNA can only reveal a person’s lineage, not their precise whereabouts and movements. The authors list North Africa and West Asia as plausible locations for the hub, but stress that we need older genomes to know for certain.