Evolution of the dad

Lee Gettler is hard to get on the phone, for the very ordinary reason that he’s busy caring for his two young children. Among mammals, though, that makes him extraordinary.

“Human fathers engage in really costly forms of care,” says Gettler, an anthropologist at the University of Notre Dame. In that way, humans stand out from almost all other mammals. Fathers, and parents in general, are Gettler’s field of study. He and others have found that the role of dads varies widely between cultures — and that some other animal dads may give helpful glimpses of our evolutionary past.

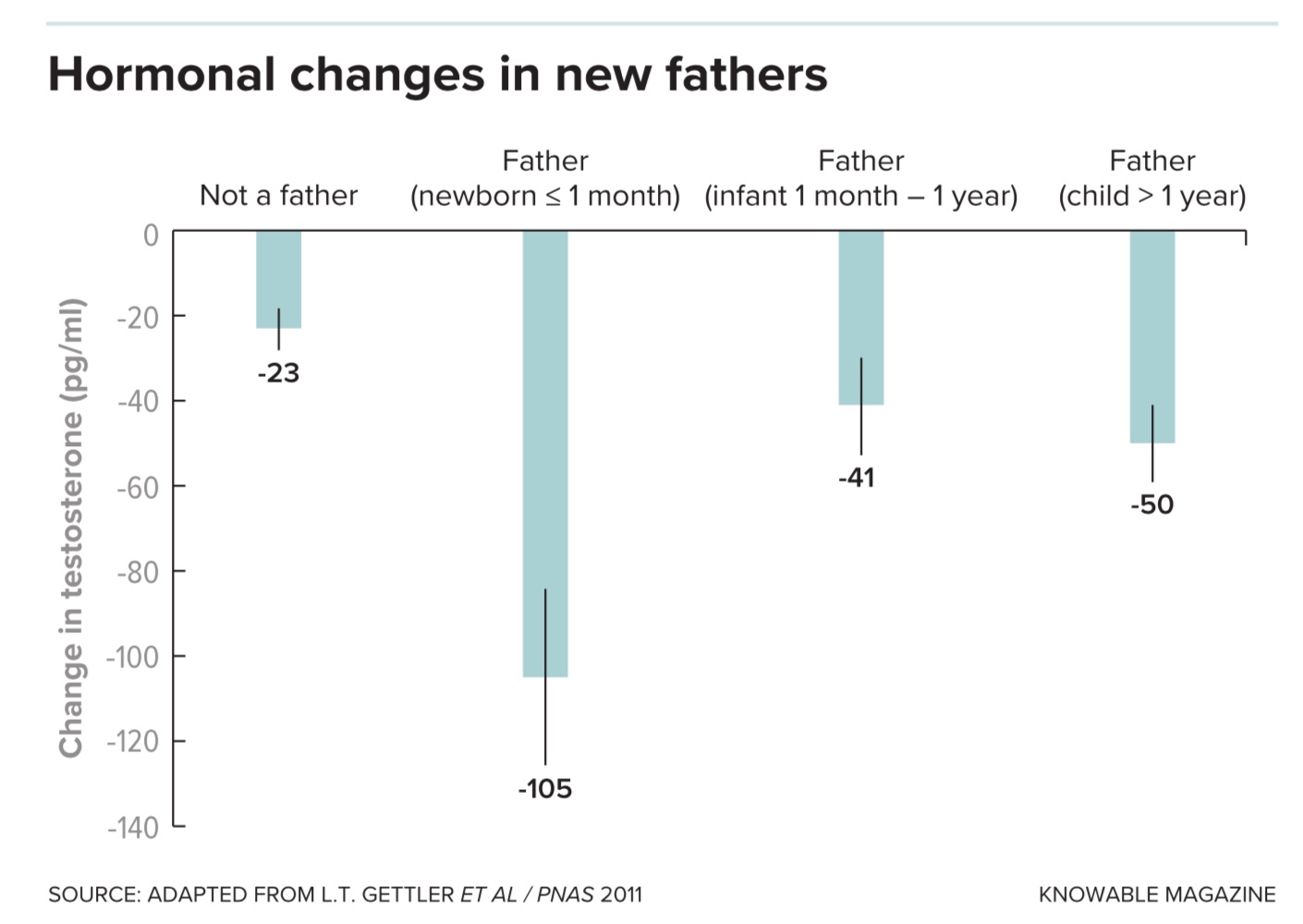

Many mysteries remain, though, about how human fathers evolved their peculiar, highly invested role, including the hormonal changes that accompany fatherhood (see sidebar). A deeper understanding of where dads came from, and why fatherhood matters for both fathers and children, could benefit families of all kinds.

“If you look at other mammalian species, fathers tend to do nothing but provide sperm,” says Rebecca Sear, an evolutionary demographer and anthropologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Moms carry the burden in most other animals that care for their kids, too. (Fish are an exception — most don’t tend their young at all, but the caring parents are usually dads. And bird couples are famous for co-parenting.)

Even among the other apes, our closest relatives, most dads don’t do much. That means moms are stuck with all the work and need to space out their babies to make sure they can care for them. Wild chimps give birth every four to six years, for example; orangutans wait as long as six to eight years between young.

The ancestors of humans, though, committed to a different strategy. Mothers got help from their community and their kin, including fathers. This freed them up enough to have more babies, closer together — about every three years, on average, in today’s nonindustrial societies. That strategy “is part of the evolutionary success story of humans,” Gettler says.

Fatherhood in the blood

Some clues to the evolutionary history of fatherhood are written in the molecules of men’s bodies.

Anthropologist Lee Gettler worked on a long-term study of men in the Philippines, gathering biological data from them in their early 20s and following up five years later. He and his colleagues found that men with higher testosterone in their early 20s were more likely to have partners and children later on, when researchers followed up. But those new dads no longer had high testosterone — it had dropped dramatically, especially if they had a newborn at home. Once a man’s youngest child was a toddler, his testosterone began to creep back upward.

Testosterone is linked to mating and competitive behavior in male animals. Suppressing it might be nature’s way of preparing fathers to cooperate with their partners and care for children, the researchers say. Although caring fathers are rare among mammals and most other animals, many can be found among birds — and those bird fathers also experience testosterone dips.

Prolactin is another hormone linked to paternal behavior in birds — this time, doting bird dads have more of it — and some studies have hinted at a similar effect in humans. Although we’re only distantly related to birds, evolution may have used the same mechanisms to encourage fatherly behavior in both animals. Understanding those mechanisms better might help us learn how fatherhood evolved.

“If we understand the physiological pathways that underpin care in those other species, we can look to see if the same signatures occur in human fathers,” Gettler says.

Doting gorilla dads

Some clues about the origin of doting fatherhood come from our close primate relatives. Stacy Rosenbaum, a biological anthropologist at the University of Michigan, studies wild mountain gorillas in Rwanda. These gorillas provide intriguing hints about the origins of ape dads, as Gettler and coauthors Rosenbaum and Adam Boyette argue in the 2020 Annual Review of Anthropology.

Mountain gorillas are a type of eastern gorilla. They differ from western gorillas — a separate species, more often seen in zoos — in their habitat and diet. Rosenbaum is more interested in another thing that sets mountain gorillas apart: “Kids spend a ton of time around males,” she says.

Those males may or may not be their dads. Male mountain gorillas don’t seem to know or care which young are theirs. But nearly all males tolerate the company of kids. Unlike any other great ape that’s been studied in the wild, these males — bruisers twice the size of females, with huge muscles and teeth — are essentially babysitters. Some pick up the kids, play with them and even sleep cuddled together.

This male company can protect very young gorillas against predators, and it keeps the young from being killed by intruding males. Another important benefit might be social, Rosenbaum speculates. The young gorillas mingling around an adult male might pick up social skills like human toddlers do from their peers at daycare. Additionally, research has shown that the relationships between young gorillas and adult males persist as those kids grow up.

Another tantalizing hint about how male gorillas benefit the young in their group comes from a recent paper on young mountain gorillas whose mothers died. Losing their mothers didn’t make these orphans more likely to die themselves, the researchers found. Nor did they experience other costs, such as a longer wait before having their own young. The orphans’ relationships with others in their group, especially dominant males, seemed to protect them from ill effects.

Mountain gorilla males aren’t the only primates to ally with kids. Adult male macaques also spend time with young. And baboon males form “friendships” with females and their young, which are often (but not always) their own offspring. These behaviors cost the male primates almost nothing. So while the males may give their own kids a survival boost, it’s not a big deal if they spend time with some unrelated kids too.

Are dads sexy?

But babysitting may benefit male gorillas in another way, too: by making them more attractive. “One of our speculations is that females actually prefer mating with males who do a lot of interacting with kids,” Rosenbaum says. She’s found that male gorillas who do more babysitting earlier in life go on to father many more children when they’re older. Macaques, too, seem to be more attractive to females if they’ve spent more time hanging out with kids.

Anthropologists used to assume that fatherly behavior could evolve only in monogamous animals, Rosenbaum says. Species like the mountain gorillas undermine that assumption. They also show that, despite what scientists have long thought, male animals don’t have to choose between spending their energy on mating or parenting. It seems taking care of kids can be a way of getting mates.

Studies of human dads and stepdads have hinted at the same idea. “A lot of guys will willingly enter into relationships with kids they know aren’t theirs,” says Kermyt Anderson, a biological anthropologist at the University of Oklahoma. That investment might seem paradoxical from an evolutionary perspective. But Anderson’s research suggests that men invest in stepkids and even biological kids partly as an investment in their relationship with the mother. When that relationship ends, fathers tend to become less involved.

A human dad who cares for his children or stepchildren is different, of course, from an ape or monkey who just lets kids hang around. But Gettler and Rosenbaum wonder whether our own ancestors had similar habits to a mountain gorilla or macaque. Under the evolutionary pressures they faced, these friendly tendencies toward kids could have ratcheted up into devoted fatherhood.

Many kinds of fatherhood

It’s clear human fathers are unusual in their attention to their children. “However, it’s also clear that fatherhood in humans is quite variable,” Sear says. Not all dads are doting, or even present.

But that doesn’t necessarily affect basic survival. In a 2008 paper, Sear and coauthor Ruth Mace asked whether children with absent fathers are likelier to die. They reviewed data on child survival from 43 studies of populations around the world, mostly those without access to modern medical care. They found that in a third of the studies looking at fathers, kids were more likely to survive childhood when their dad was around. But in the other two-thirds, fatherless kids did just as well. (By contrast, every study of children without mothers found they were less likely to survive.)

“That is not what you would expect to see if fathers are really vital for children to thrive,” Sear says. Rather, she suspects that what’s vital are the jobs fathers perform. When a father is missing, others in the family or community can fill in. “It may be that the fathering role is important, but it’s substitutable by other social group members,” she says.

What is that role? Historically, Gettler says, anthropologists have viewed fatherhood as all about “provisioning” — bringing home the bacon, literally. In some foraging communities, more successful hunters also father more kids. But Gettler hopes to help expand the definition of a dad. Research has shown that fathers can have important roles in directly caring for their children, for example, and teaching children language and social skills. Fathers may also help their children by cultivating relationships in their communities, Gettler says. When it comes to survival, “Networking can be everything.”

A dad’s job also varies culturally. For example, in the Republic of the Congo, Gettler works with two neighboring communities. The Bondongo are fishers and farmers; they value fathers who take risks to gain food for their own families. Their neighbors, the BaYaka, are foragers who value fathers who share their resources outside their families.

“In the West we have this idealization of the nuclear family,” says Sear: a self-reliant, heterosexual couple in which Dad does all the provisioning and Mom all the childcare. But worldwide, she says, families like this are very rare. A child’s biological parents may not live together exclusively, for life or at all, Sear writes in a recent paper. Childcare and food can come from either parent — or neither. Among the Himba of Namibia, for instance, children are often fostered by extended family.

“Possibly the key defining feature of our species is our behavioral flexibility,” Sear says. Assuming that certain roles are “natural” for fathers or mothers can make parents feel isolated and stressed, Sear writes. She hopes research can broaden our understanding of what fathers are for, and what a human family is. That might help societies to better support families of all kinds — whether they have dads like Gettler who are busy chasing the children around, or dads who are away fishing, or no dads at all.

“I think we need to take a much more nonjudgmental view of the human family, and the kinds of family structures in which children can thrive,” Sear says, “to improve the health of mothers, fathers and children.”

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, a nonprofit publication dedicated to making scientific knowledge accessible to all. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter.