When the government tried to flood the Grand Canyon

The channeling of the Colorado River to irrigate farmlands and provide water to cities across the southeast has been a complex, contentious issue for more than a century. One chapter in that story, highlighted by historian Byron E. Pearson, was the federal government’s plan to build two huge dams in the Grand Canyon.

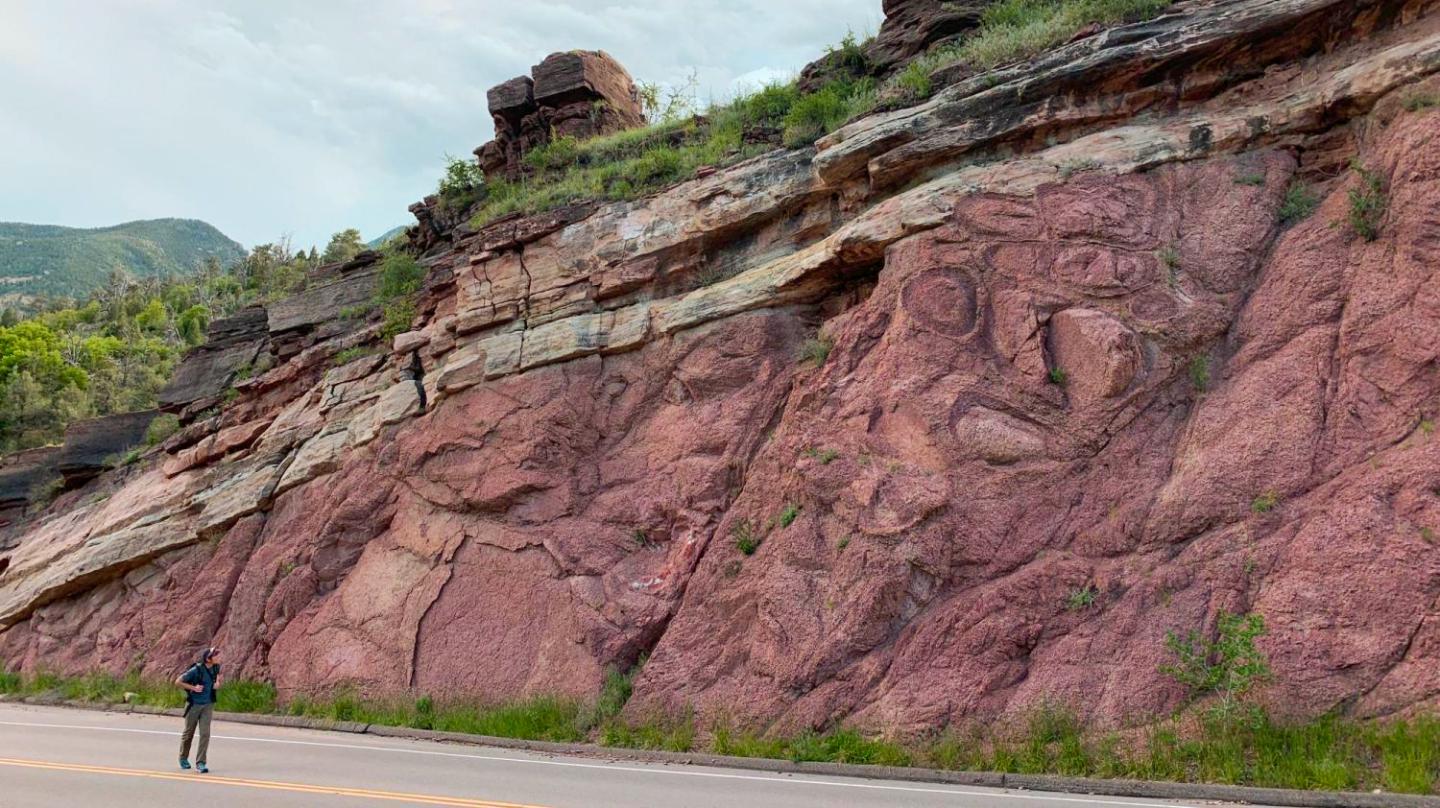

In the 1960s, western politicians and federal bureaucrats were formulating what would become the Central Arizona Project (CAP), which brings water from the river to central and southern Arizona. To provide the power needed to move the water, they proposed the construction of two hydroelectric dams in the Grand Canyon. The chosen locations were outside the protected parts of the canyon, but the reservoir created by one of the dams would have flooded a significant part of Grand Canyon National Park.

Initially, debate over the plan centered on disagreements among western politicians—notably a push by California congressmen to ensure that their state wouldn’t lose out on its allotments of Colorado River water. But soon after, the Sierra Club and other conservation activists began appealing to politicians and the public to save the canyon. By 1966, national publications like Reader’s Digest and Life magazine were reporting on the issue, bringing the idea of conserving natural wonders to many citizens for the first time.

“The movement to save the Grand Canyon from inundation began to resemble a national referendum on conservation,” Pearson writes. “Sacks of letters from ordinary citizens, a great preponderance of which opposed the dams, arrived daily on Capitol Hill.”

For some in the federal government, all this came as a shock. Prior to the controversy, Pearson writes, the Department of the Interior and other related agencies had spent six decades building massive construction projects that irrigated the dry West, transforming millions of acres. During that time, few politicians had stood in their way and the majority of citizens had generally supported the policies.

“Now it faced growing opposition, not just from a handful of environmental extremists, but from ordinary Americans,” Pearson writes. The reputation of the department shifted “from that of a heroic government agency which brought life and prosperity to an arid wasteland to that of a villain who would desecrate the country’s natural wonders so that a few special interests could profit.”

At the behest of government officials, the Internal Revenue Service notified the Sierra Club that it would review the organization’s tax-exempt status due to its efforts to influence legislation. This backfired spectacularly, with national newspapers presenting the issue as an attack by powerful bureaucrats on a small, idealistic organization. Thanks to this coverage, more of the public became aware of the Grand Canyon issue, and the Sierra Club was flooded with donations, which it used to publicize the issue even more.

Ultimately, CAP moved forward in 1968, powered by a coal-fired plant rather than the dams. The Grand Canyon was saved, and millions of Americans had become more attuned to conservationists’ concerns.

This article appeared on JSTOR Daily, where news meets its scholarly match.