- Everything you read in a history book has been written by someone with an agenda and biases.

- A surprising amount of history has been handed down to us through the works of nonhistorians.

- Here, we look at how people like Herodotus, Shakespeare, and Tolstoy have defined history.

In Tom Stoppard’s play Night and Day, two journalists are talking about the newspaper they work for.

“This is an objective fact-finding organization,” one says.

The second person nods knowingly. “Yes, but is it objective-for or objective-against?”

There is scant little that can be called “objective” when it comes to history. History is not about the past but stories of the past. Every historian, from Herodotus to Niall Ferguson, has an agenda. They choose what to include and what to cut, what to emphasize and what to downplay. If we’re looking for facts — indisputable, undeniable facts — we have precious few about anything pre-20th century. And so we rely on imagination, guesswork, and narrative.

History is a story, and we know who the storytellers are. Richard Cohen’s book Making History: The Storytellers Who Shaped the Past is an impressive 750-page effort to unpack the creation of history. Here are a few of the book’s most influential figures: the people who wrote our history.

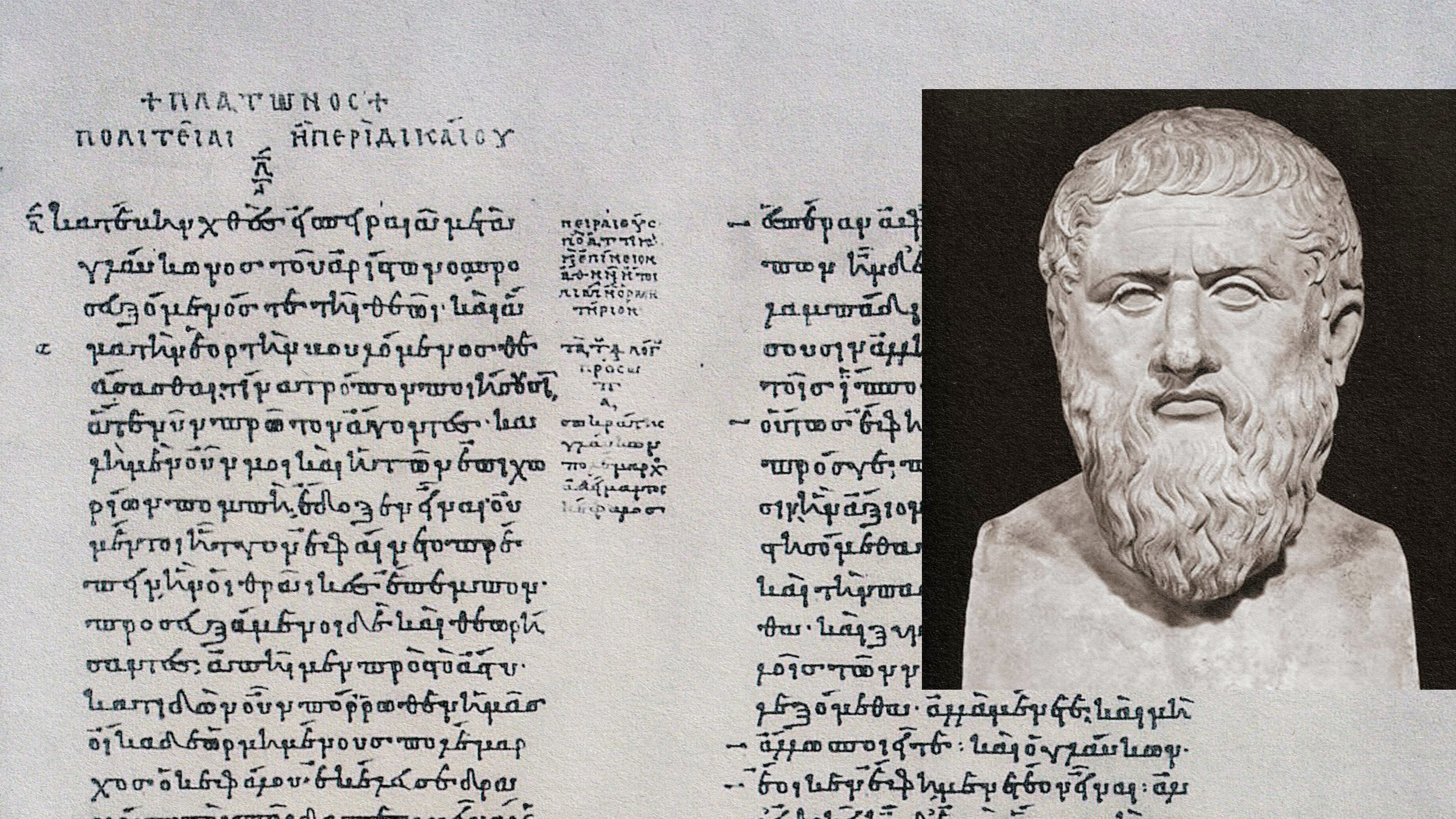

Ancient Greece and Persia

Cicero once called Herodotus “The Father of History.” Perhaps more astutely, Plutarch dubbed him “The Father of Lies.” It’s from Herodotus that we learn about the brave, underdog Greeks defeating the overwhelming Persian hordes. However, Herodotus’ job in recounting the Greco-Persian Wars was not documenting history but spreading propaganda. He claimed that the Persian forces bankrupted cities as they passed by, and, as Cohen puts it, if “his suspiciously precise figure of 5,283,220 men” were true, then the Persian column would have run from eastern Greece to western Iran.

Herodotus was not a historian in any modern sense (his contemporary, Thucydides, does a much better job). It would be more accurate to call him a researcher and retitle Histories as “My Travels.” He claims to have witnessed a thousand exciting events first-hand. Some were plausible, but others involved gold-digging ants and talking animals. Herodotus was not in the business of writing a factsheet. His Histories is an entertaining adventure involving local beliefs, folklore, and mythology — with some history scattered in and among the legends.

Judea

The Old Testament is the story of a people building a nation through narrative and theology. As such, if you’re hoping to do history, it’s best treated as a single, biased source. The Oxford theologian John Barton, author of The History of the Bible, puts it like this: “There is probably not a single episode in the history of Israel as told by the Old Testament on which modern scholars are in agreement.”

That is not to say the Old Testament is filled with lies. Some of it can be verified and fact-checked by other sources, such as Persian historians. However, a lot, especially the earlier events, cannot.

As Cohen writes, “We do not have external evidence that kings called Saul, David, or Solomon ever existed — no traces that archaeologists can examine, no mentions in the records of other nations in the region.”

However, these stories’ placement in the Bible made them immune to historical critique for much of Western history. For instance, the Catholic Church excommunicated the Dutch Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza in 1656. Among his 36 acts of wrongdoing was claiming that the Bible should be no more privileged as a source of history than any other document. For this heinous crime, he was cut off from civil society and even had attempts on his life.

Shakespeare

Shakespeare’s plays are typically divided into three categories: comedies, tragedies, and histories. But it’s absurd to think that a playwright — a man whose job is to entertain people — would suddenly become a paragon of historical rigor for a third of his plays. Shakespeare had no more duty to historical fact than Mel Gibson.

Shakespeare himself seems to mock the idea. He claimed King Lear, a play about a king in legend only, was a “true chronicle history” while The Taming of the Shrew was “a kind of history.”

The problem is that so many of Shakespeare’s exaggerated or utterly invented depictions have entered our historical understanding. Because of Shakespeare, we imagine Cleopatra as indescribably beautiful and Mark Antony as a drunken boor. He portrayed Tudor kings as noble, handsome, martial, and wonderful (his royal patrons being the Tudors) and Richard III as a hunchback, infanticidal git who was the bogeyman of English history for centuries. Today, we compare all that’s bad to Hitler. For the English, that person used to be Richard III. And it’s all down to Shakespeare.

The novelists

If asked to imagine an archetypal Scot — a fancy dress version of Scottishness — most people would think kilts and bagpipes. The problem is that these are almost entirely the 19th-century inventions of Walter Scott. Bagpipes originated in Egypt, and kilts were new arrivals. The point, though, is that they are Scottish now. Scott’s Scotland reveals a good point: The last two hundred years have been the work of the historical novel.

So much of our cultural understanding of particular historical periods comes from novelists. Leo Tolstoy defined the Napoleonic Wars, and Victor Hugo the French Revolution. James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans established popular opinion regarding Native Americans and frontiersmen. More recently, Hilary Mantel, Julian Fellowes, and Bernard Cornwell have all defined history. It’s history written by novelists.

That all said, we should not disparage the historical novelist. Tolstoy did more research and first-hand investigation than most historians when he wrote War and Peace. Charles Dickens had his friend, Thomas Carlyle, send him cartloads of books when writing of A Tale of Two Cities. And Hilary Mantel refuses to change any facts that are known about a period when dramatizing it.

The lessons of history

History is written by historians, and historians are people. Whenever you hear a fact or are given a stereotype, it’s always a good idea to check where that comes from because the voices we heed and the books we read will ultimately define how we see ourselves.

As George Orwell famously wrote: “Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.” And with President Xi rewriting history books and the ongoing debates around what we should teach our children, learning who wrote our history and why is more important than ever.