How humanity became slaves to the clock

- In a time before clocks, historians refer to life as being “task-oriented.”

- People would use metaphors and comparisons to explain a unit of time, such as the time it takes to say a prayer.

- Today, clocks are necessary for highly complex and demanding economies. They are now our masters.

My three-year-old doesn’t understand time. I don’t mean “time” in an Einsteinian kind of way, but the basic units of time. He doesn’t know what minutes or hours are. “Yesterday” could be the day before, or it could be April. When he asks how long his porridge will take to cook, I say, “A bit.” The problem is that I’ve quickly discovered that “a bit” is a woefully inadequate descriptor. And so, I’ve taken to using comparisons. I say, “It takes as long as a bath,” or, “It’ll be one episode of Spiderman.” I still don’t think he gets it, but at least I’m trying.

What I’m doing isn’t unique. Millennia ago, people lived without clocks, so there was literally a time before time. And they did exactly what I do with my young boy: They used metaphors. In medieval England, for instance, they had a time measure called the “Pater Noster Whyle,” which was how long it took to say the Lord’s Prayer. And some things would take a “Pissing Whyle.”

So, what was life like without clocks, and how much have clocks changed how we see ourselves and the world?

Life before clocks

Up until the late Middle Ages, people didn’t think of time as something separate from the jobs they did. Mowing the lawn wouldn’t take “half an hour”; it would take the time it took to mow the lawn. Historians tend to call this a “task-oriented” lifestyle. This means that time was seen in terms of how long the task took; it wasn’t divided by hours, minutes, or seconds. As Oliver Burkeman puts it in his book, Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals:

“You milked the cows when they needed milking and harvested the crops when it was harvesttime, and anybody who tried to impose an external schedule on any of that — for example, by doing a month’s milking in a single day to get it out of the way, or by trying to make the harvest come sooner — would rightly have been considered a lunatic.”

The point is that before the invention of the clock, there was no 9-5. There could be no clock watching without a clock. The work was done and the harvest was brought in. Most people would expect to work daylight hours, which meant long, sixteen-hour days in the summer, and a much shorter eight hours in the winter. There was no rushing to finish a task due to some artificial time constraints. As every slow-moving, easy-going old hand will tell you, “It takes as long as it takes.”

Industrialists and their time pieces

Of course, I suspect you aren’t reading this after a hard day milking cows. Most people today work jobs that involve an office or factory. If you are going to hold a meeting in a specific room with specific people, saying, “Let’s gather after lunch,” is a bit too vague. It’s hard to catch a train, “After I’ve brushed my teeth,” or to watch a movie at the cinema “when the sun goes down.”

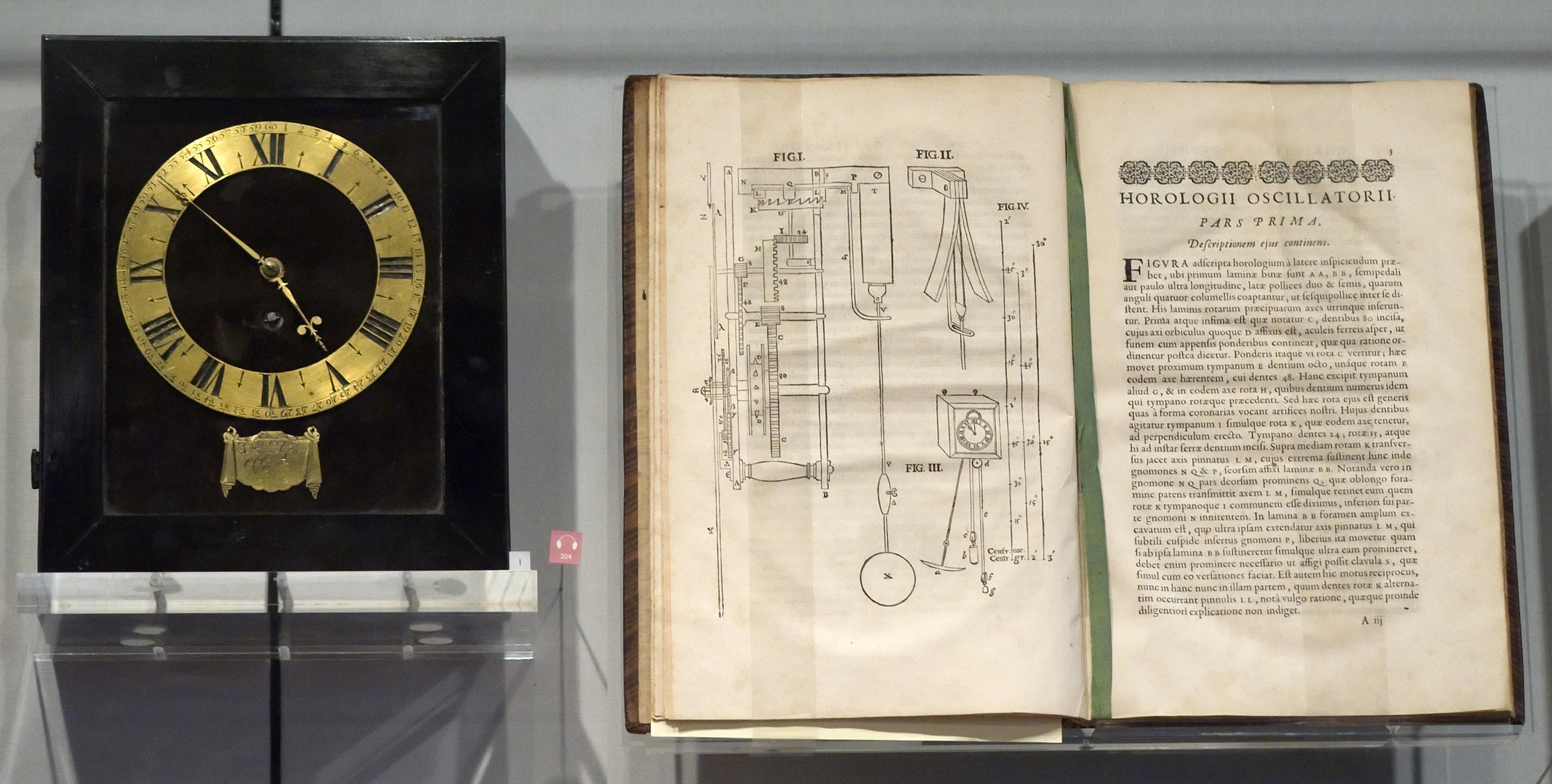

As Europe industrialized, the task-oriented flexibility of agrarian life was yanked to a gear-crunching halt. The first major corporation to use clocks regularly was the British postal service, followed by the train companies. But, soon enough, everyone saw the benefit of living by the clock. It’s hard to coordinate factory workers and choreograph manufacturing without a clock. Industrialization needed workers to get to their jobs “on time.” Output, productivity, and efficiency demanded a clock.

Slaves to the clock

When you study the history of ideas, it’s often easy to project your own life into the lives of those who came before. Without the clock, it’s hard to imagine how society managed. Conversely, to a medieval farmer looking in on us, our lives today would be utterly alien or dystopian.

Clocks have completely uprooted and reoriented how we see the world. Just think about how often you check the time on your phone or watch. Your life is run by the clock. It’s like we have divided our lives into tiny blocks, and we put bits of ourselves into those blocks. Things used to be “task-oriented.” The world moved as the world moved. Now, we try to stretch and break the world to meet the demands of the clock. The clock never lies, and I must not be late. The Clock Overlords will be displeased.

Sometimes, though, we need to throw off our ticking chains. Not everything in life has to be divided into neat segments, like lessons of a school day. Occasionally, it’s good just to let the world happen. We need not only to accept that fact but to tell other people that “it will take as long as it takes.”