Found: 439 million-year-old fossil is the oldest jawed ancestor of sharks

- Paleontologists suspect that jaws evolved some 450 million years ago in aquatic species. But the fossil record contains no jawed species older than 425 million years.

- In a critical fossil site in South China, scientists may have found the missing pieces in the fossil record. Among thousands of specimens, they found a new species of ancestral shark that is 439 million years old — the oldest species discovered with a fully articulated jaw.

- The discovery provides essential insights into the evolution of jawed vertebrates, including humans.

The evolution of the jaw gave our vertebrate ancestors significant advantages that allowed them to radiate across the globe. With a mean bite, they could exploit more food sources. They were more effective both in predation and defense.

The importance of the jaw is not under debate, but its evolutionary timeline is. We know that the jaw is incredibly old, evolving somewhere between 425 million and 450 million years ago in fish. In fact, jawed vertebrates appeared some 200 million years before the dinosaurs.

Yet there is a significant discrepancy between when molecular and phylogenetic models suggest jawed vertebrates appeared — around 450 million years ago — and the age of the oldest jawed vertebrates in the fossil record, which are around 425 million years old. Researchers have long struggled to explain the discrepancy.

Scientists might have closed this gap with a remarkable fossil finding in southern China. In a series of four papers published in Nature, a group of paleontologists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qujing Normal University, and the University of Birmingham describes several new species that reveal a previously undocumented diversification of jawed vertebrates.

The findings provide the most robust support yet for the idea that jawed vertebrates radiated widely long before what the fossil record shows.

Fishing for luck

Luck plays a significant role in paleontology. Scientists need a little fortune when they choose where to excavate, and the retrieved organisms themselves can easily be lost during the efforts to preserve them. If conditions are wrong, the fossils of key characters in our evolutionary story will be lost to history.

Sometimes, though, luck does smile upon us. The fossils in question were discovered at a site in Chongqing in 2019. The researchers quickly knew they were dealing with a Konservat-Lagerstätte — a German word describing a sedimentary layer with organic remains that are extraordinarily well preserved.

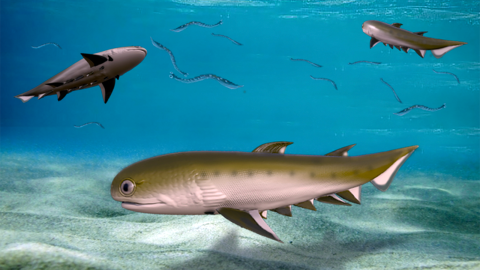

In the Chongqing Lagerstätte, scientists found more than ten genera of jawed fishes. All the specimens were small and delicate, suggesting that in anything outside of a Lagerstätte context, they would have been lost to environmental degradation or scavengers. Many aquatic organisms of the period in question were primarily made of cartilage, a material much less likely to survive across geological time. The Chongqing Lagerstätte findings gave scientists a remarkably rare glimpse into life half a billion years ago.

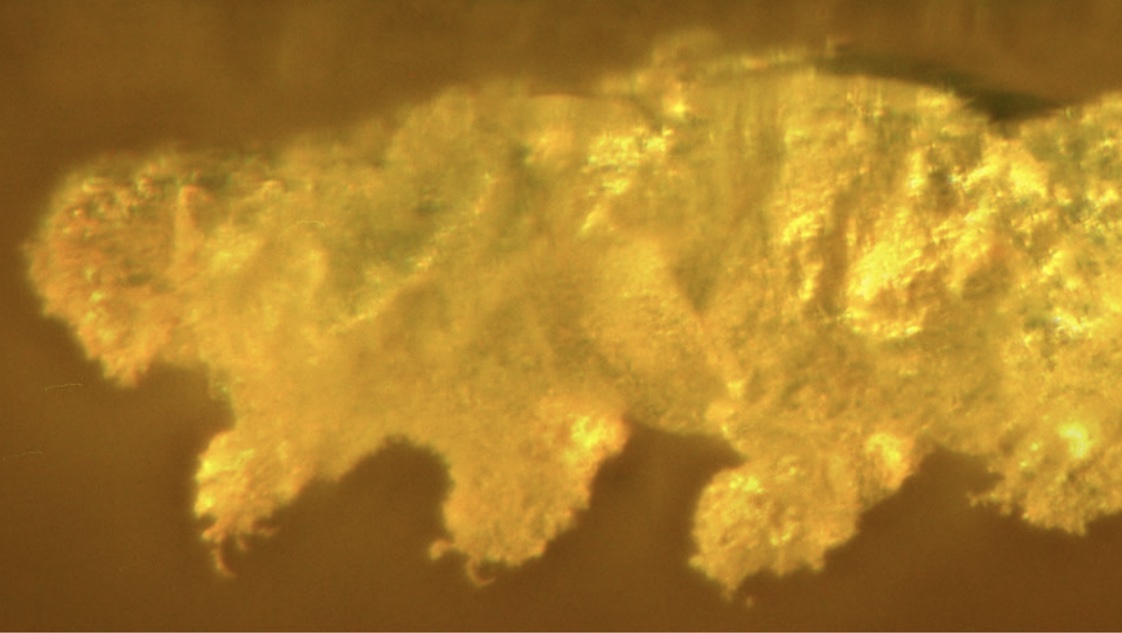

Among the assortment of fossils, the most striking discovery was Fanjingshania renovata. (Fanjingshania is named for Mount Fanjing, a UNESCO site situated around 100 km northeast of the type’s locality. Renovata is Latin for “renewal,” alluding to the species’ ability to remodel its bones.) The site held a startling 1,000 specimens of this species, and the researchers determined they were about 439 million years old.

Fanjingshania did not immediately fit into any known group. Though the jawed fish possesses dermal shoulder plates and fin spines common to chondrichthyans (cartilaginous fishes), its bones show the kind of extensive remodeling associated with the skeletal development of bony fish — and of humans.

Rewriting history

The scientists used phylogenetic modeling to confirm their hypothesis that Fanjingshania represents an early branch of primitive chondrichthyans, pushing back the age of stem chondrichthyans by about 20 million years. Also, because Fanjingshania had both bony and cartilaginous fish traits, scientists will be better able to identify precursors to sharks and bony fish, allowing us to map out the evolution of these fish lineages more precisely. For example, shark-like scales from the Ordovician period are probably sharks with characteristics much like Fanjingshania.

Professor Zhu Min of the Chinese Academy of Sciences said in a statement that “the new data allowed us to place Fanjingshania in the phylogenetic tree of early vertebrates and gain much-needed information about the evolutionary steps leading to the origin of important vertebrate adaptations such as jaws, sensory systems, and paired appendages.”

Along with Fanjingshania, scientists describe other findings like Tujaaspis vividus, a jawless fish in a group called the galespids that preserves poorly. In fact, of the tens of thousands of galespid fossils we have, most are just heads. The Tujaaspis vividus in this excavation is the first nearly intact specimen researchers have found.

Additionally, Quiandus duplicus, found in the Guizhou province, has the oldest teeth of any animal previously described, by around 14 million years. Finally, another paper describes Xiushanosteus mirabilis and Shenacanthus vermiformis, both jawed fishes. These discoveries might help add to our understanding of the emergence of jawed vertebrates.

These breakthrough discoveries add more data to a critical and formerly obscure part of vertebrate evolutionary history. Tracing the origin and development of jaws — and other anatomical features that humans share — does more than just satisfy our curiosity. It helps shed a little light on the mystery of how we came to be.