A mammoth graveyard: 60 pachyderm skeletons discovered together in Mexico

Image source: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH))

- During digging for a new airport in Mexico, workers came across three sites containing the remains of mammoths, as well as some pre-Spanish human burial sites.

- It’s unclear why the mammoths were all found in this one spot, though it may have to do with an ancient lake.

- Retrieving this massive sample will likely give experts new insights into a long-lost North American pachyderm.

In the Mexico Basin about 45 miles north of Mexico City in the Santa Lucía region, the new Felipe Ángeles Airport is under construction. According to Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), workers there have dug up a massive surprise: a trove of 60 ice-age mammoth skeletons. They’ve also unearthed 15 pre-Hispanic human burial sites.

Image source: Sergiodlarosa/wikimedia

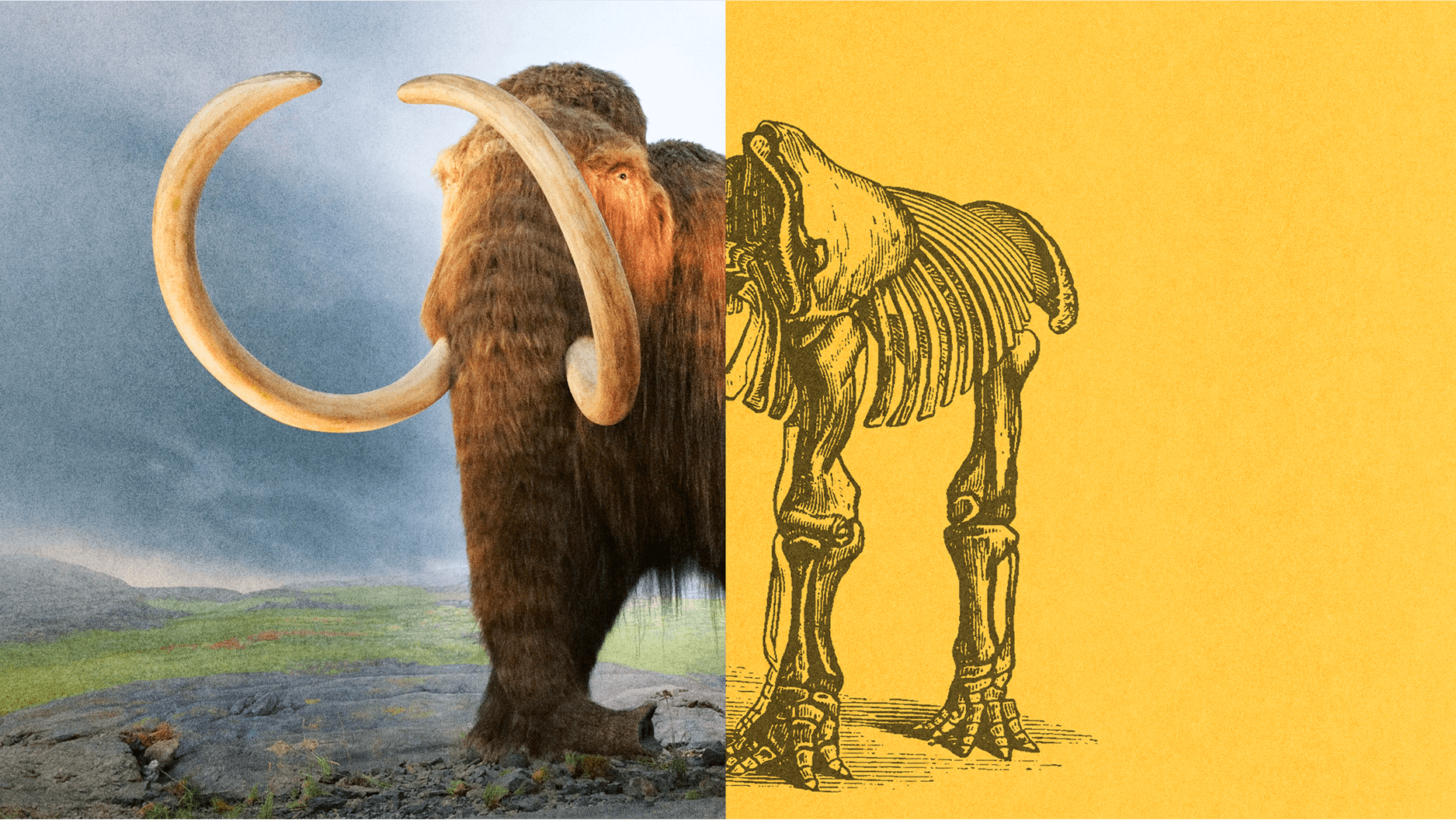

The pachyderm bones belong to Colombian mammoths, Mammuthus columbi, who last lived in North America in the Pleistocene epoch between 2.6 million and 13,000 years ago, when they are believed to have become extinct. They’re the mammoths that visitors to Los Angeles’ La Brea Tar Pits encounter. (No woolly mammoth remains were found in Santa Lucía.)

It’s not yet known how many of the mammoth skeletons are complete. It is clear, though, that males, females, and their young are there. The bones are being found between 80 centimeters and 2.5 meters below the surface and spread across three exploration areas. First discovered in October 2019, the digs are still being stabilized and undergoing analysis and classification, according to INAH National Coordinator of Archaeology, Pedro Francisco Sánchez Nava.

How 60 mammoths wound up together in death at this location is an interesting question. No signs of human tracks leading to or from the site are evident nor have any indications of hunter accommodations have been found. By contrast, the prehistoric mammoth hunting site discovered in the Mexican municipality of Tultepec in November 2019 does exhibit such signs of human interaction.

Archaeologists suspect the 60 mammoths got stuck in a muddy swamp over time — the site is near the shores of the former Lake Xaltocan. Researchers say the most complete skeletons found are those close to the former lake’s shoreline. It remains possible that the immobilized mammoths were then preyed upon by hunters even without clear evidence of that so far.

Once the remains are retrieved, they’ll be studied by a team of 30 archaeologists, supported by a trio of restorers, to make a full account of what’s been found. They hope to learn more about how and precisely when the animals lived, ate, and what health issues they may have had as evidenced in their skeletal remains.

Image source: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia

Meanwhile, construction of the new airport continues. Says Salvador Pulido Méndez, director of INAH Archaeological Salvage, “So far, no findings have been recorded on the land that lead to the rethinking of the construction site, either totally or partially. Rather, the works have allowed INAH a research conjuncture in a space where, although it was known of the existence of skeletal remains, they had not had the opportunity to locate, recover and study them.”

Prior to the beginning of construction, the Santa Lucía region had been used by the Santa Lucía Military Air Base, and the national defense organization Sedena has preserved its historic Santa Lucía hacienda, integrating it within the new airport. The various parties involved plan to create a museum within the hacienda that will allow visitors to learn about the Santa Lucía region and its amazing mammoth mammoth graveyard.