Mansa Musa and the mythical African king who may (or may not) have sailed to the Americas

- The predecessor of Mansa Musa, a wealthy king of the Mali Empire, allegedly left home to explore the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

- The idea that he may have discovered the Americas well before Christopher Columbus captures the imagination of many. But historians doubt Mali had the technology to carry out such a voyage.

- Mansa Musa, however, helped introduce West Africa to the world.

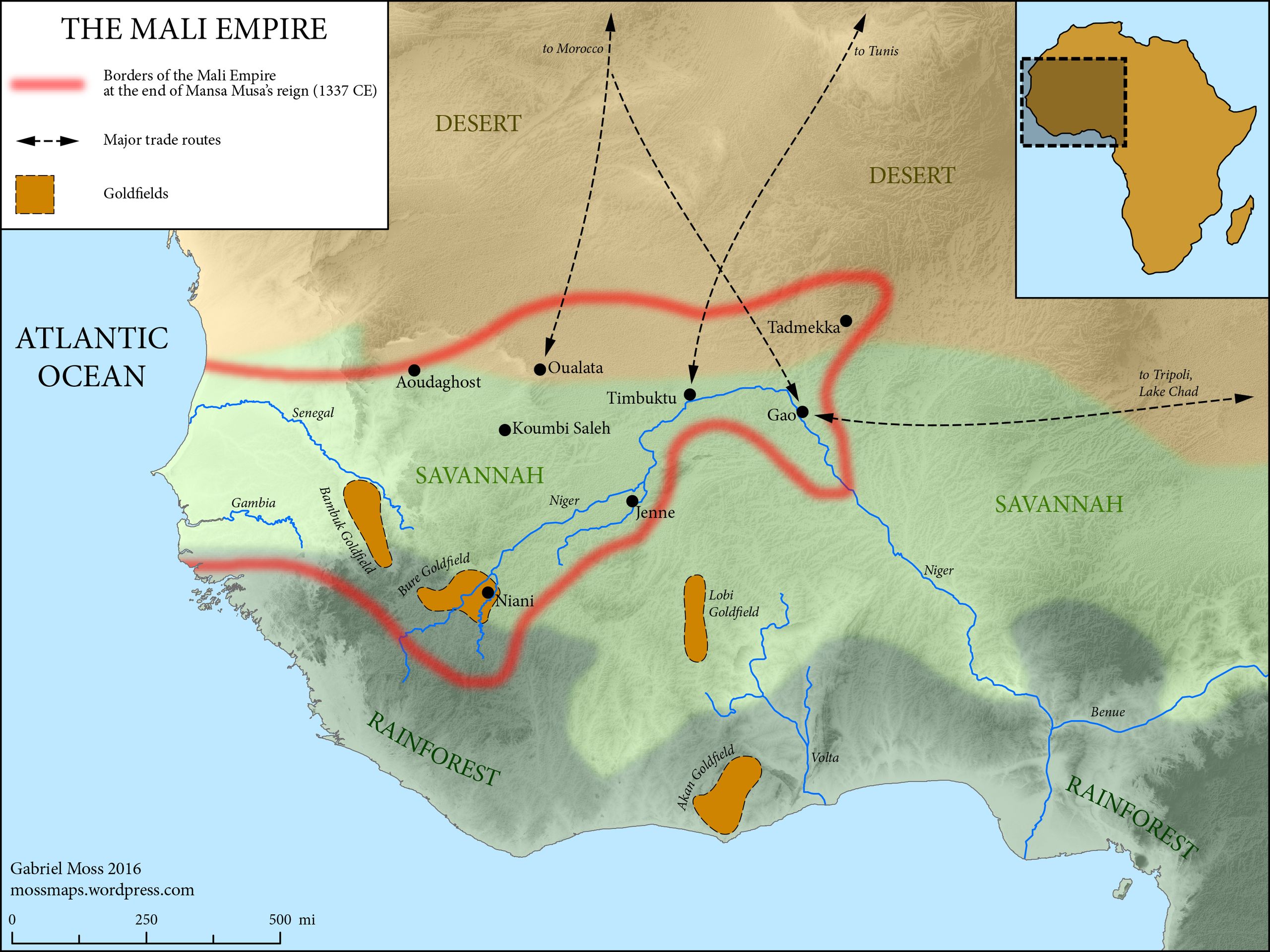

With an estimated net worth of $400 billion, Mansa Musa is considered one of the wealthiest individuals in all of world history. Although this estimate may not be wholly accurate, we do know that the Muslim king of Mali — a sub-Saharan trade kingdom rich in gold, ivory, and slaves — was so wealthy that his exuberant spending habits caused runaway inflation in the city of Cairo.

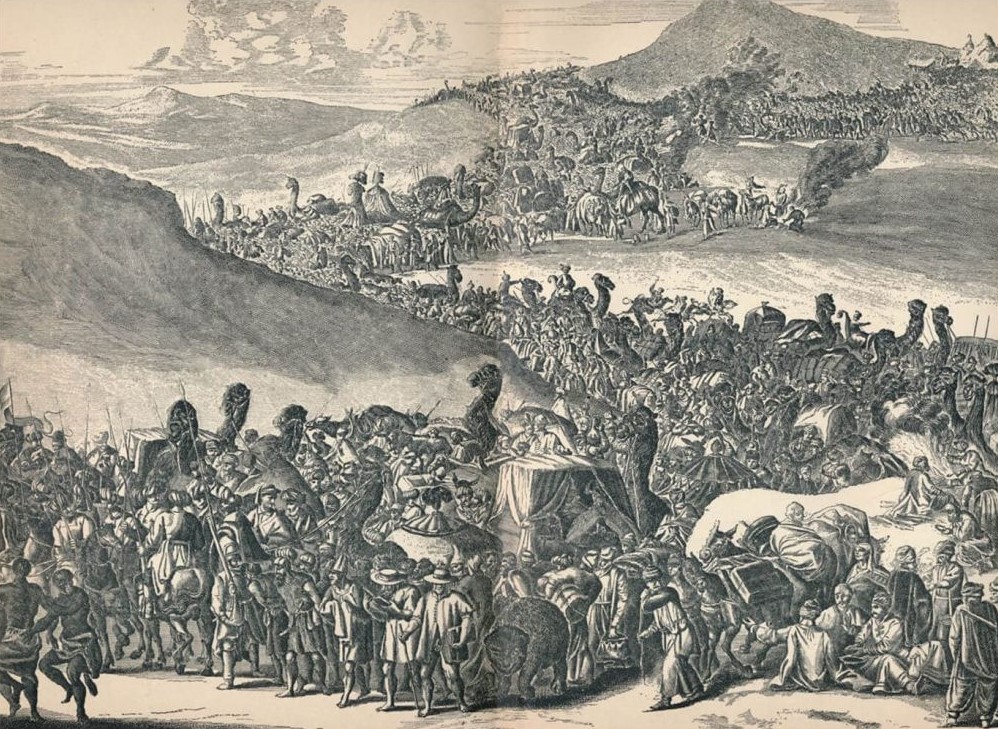

Mansa Musa passed through Cairo between 1324 and 1325 on his pilgrimage to Mecca (Hajj), the birthplace of the prophet Muhammad. On the 2,700-mile journey, he brought with him a procession of 60,000 men and 12,000 slaves, each of whom carried a gold bar or staff. The people were accompanied by a caravan of 80 camels, each of which carried around 300 pounds of gold dust. The Malian king’s pilgrimage is of interest to historians not only because it gives us an indicator of his net worth and marks a key moment in the Islamization and globalization of Western Africa, but also because it sheds light on the mysterious reign of Mansa Musa and his even more mysterious predecessor, who left his kingdom in the former’s care.

While in Cairo, Mansa Musa told its governor, the Emir Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn Amir Hajib, how he came to rule. Allegedly, he was named deputy when the previous king took 2,000 ships — “1,000 for himself and the men whom he took with him and 1,000 for water and provisions” — and set out to discover what lay on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, never to be seen or heard from again. This tale, later recounted to and written down by the Arab historian Ibn Fadlallah al-Umari, is the only one of its kind.

It’s difficult to say if it’s true or not, but if it is, it poses a number of interesting questions. Who was Mansa Musa’s predecessor? Where did he and his 2,000 ships go? Could he have discovered America a century before Christopher Columbus?

Mansa Musa’s predecessor

J. Spencer Trimingham, a scholar of Islam in Africa, wrote that:

“Sun Dyata, founder of the Mali empire, appears to have greater historical foundation, in spite of the remoteness of the event, than anything else in Mali tradition, whilst Mansa Musa, who figures so prominently in both native and external Arabic writings in consequence of his bizarre pilgrimage, is almost unknown to native tradition.”

The same goes for Mansa Musa’s predecessor, who may have been ignored in the Malian tradition because his subjects viewed his transatlantic voyage as an abdication of duty. Maybe Mansa Musa erased his legacy to secure his own. Either way, because al-Umari’s account doesn’t mention him by name, the only way to ascertain his identity is to look at where he would have belonged in the kingdom’s line of succession.

An official record of this line would not be produced until several decades after Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage. Its author, another Arab scholar named Ibn Khaldun, says Mansa Musa’s predecessor was Muhammed ibn Qu. Others attribute the voyage to Muhammed ibn Qu’s father, Mansa Qu. A third Malian, Abu Bakr, also has been listed, but only due to a 19th century mistranslation of Ibn Khaldun’s original text.

Whoever Mansa Musa’s predecessor actually was, he supposedly wasn’t the first to go out to sea. Before the king braved the Atlantic Ocean himself, he sent 200 ships with enough provisions to last them for years. Only one ship made it back, with its captain stating the fleet reached “a river with a powerful current” that claimed every vessel except for his, causing him to turn around. Most historians think the captain was referring to the Canary Current, a cold current that flows from Spain and Portugal along the northwestern coast of Africa to the equator. Assuming the fleet sailed westward, it might have reached the Amazon.

African seafaring

Though intriguing, the notion of an African explorer crossing the Atlantic has been rejected by historians. “Musa’s story is sometimes cited in support of the plausibility of the hypothesis of a pre-Columbian African colonization of the Americas,” Africanist Robin Law writes in an article, but “a more obvious reading of the story is as an illustration of West African inexpertise in oceanic navigating.”

That’s not to say oceanic navigating was completely nonexistent in Africa. Law cites a study which reveals that, long before Portuguese colonizers entered the picture, a maritime network enabled trade in pepper, kola nuts, and other goods between Cape Mount in Liberia and Cape Verde in Senegal. A similar network may have existed between the Gold Coast and Slave Coast.

Technological and environmental limitations prevented these networks from expanding in scale and scope. Strong currents, like the aforementioned Canary Current, stopped seafarers from straying too far from the coast. On top of this, the mechanisms needed to sail against the current — the sail and rudder — were not introduced to Africa until after the Portuguese arrived.

If Mansa Musa’s mysterious predecessor did not connect West Africa to the rest of the world, Mansa Musa himself certainly did. Following his pilgrimage, he enlisted architects from the Middle East to help develop the cities of Gao and Timbuktu. Arab merchants, impressed by the Malian king’s unseen wealth, followed suit, turning the empire into a cultural melting pot and hotbed for the Islamic faith.

Although Mansa Musa represented a high point, Mali endured long after his death around 1337 AD. Poor leadership and civil war caused it to fall apart in the 1460s, making way for the Songhai Empire to the east. Mali didn’t disappear entirely, however, holding on to diminished territories in the west until the 17th century, when it fell apart after its capital was sacked by the Bamana Empire.