What “national mourning” is like in various countries around the world

- On September 8, 2022, Queen Elizabeth II died. The UK government called for (at least) 17 days of national mourning.

- National mourning is a common and curious practice that varies around the world. If you don’t mourn in North Korea, you risk being executed.

- National mourning is mostly about nostalgia and the death of an era, not a person.

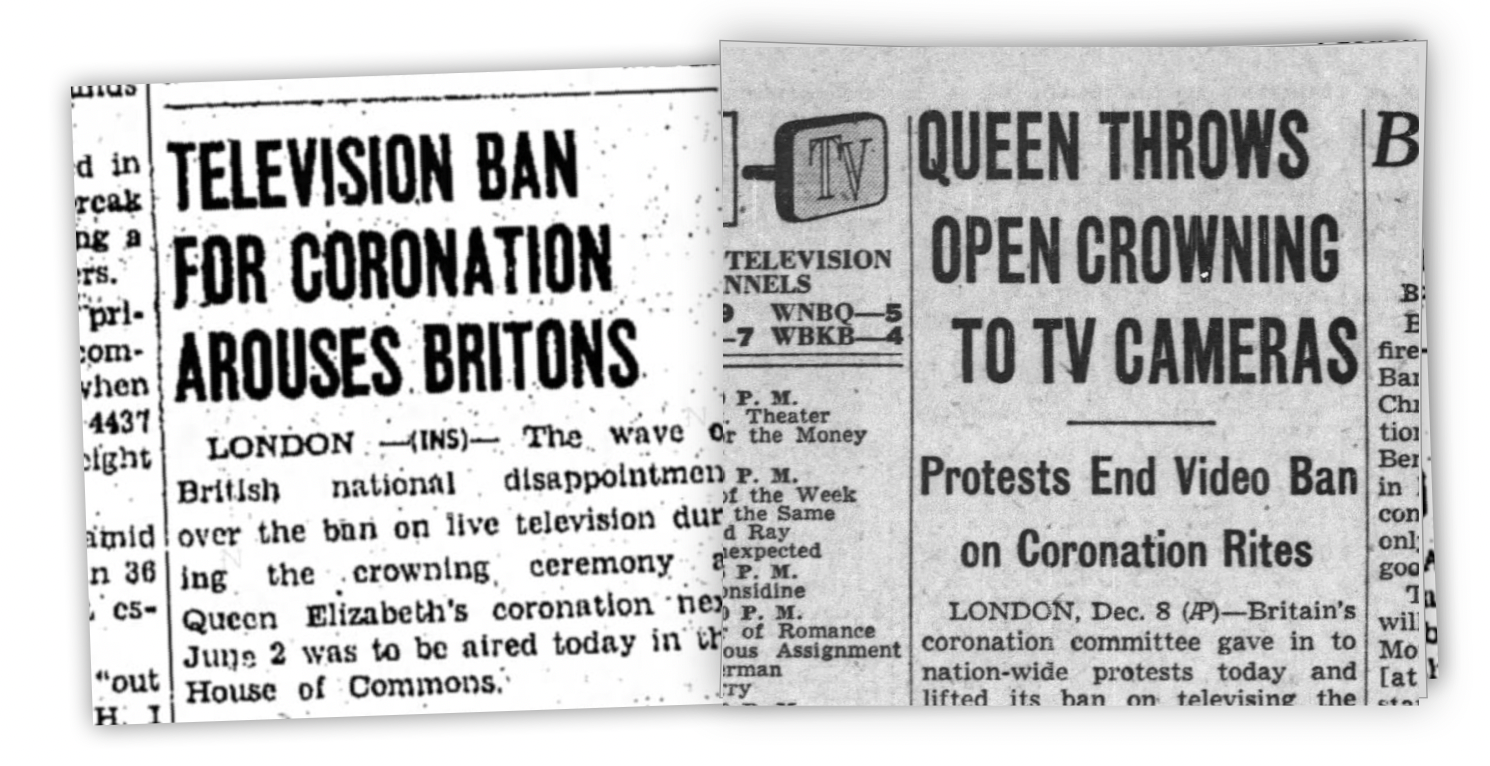

On September 8, 2022, Britain’s longest-serving monarch died. Over her 70-year reign, Queen Elizabeth II saw a lot of change. She witnessed the decline of the British Empire and decolonization, as well as the Cold War and the rise of the U.S. The world today is of a very different social, political, and technological order as the one she once knew. When she ascended the throne, it was a time of radio and Downton Abbey estates. When she died, it was one of TikTok and electric cars.

In the UK, whether you’re a Union Jack-waving monarchist or a card-carrying republican, the Queen represented steadfastness and constancy. She reigned over 15 prime ministers. In a shifting, spinning world, Elizabeth II was a rock — the unchanging center to grip onto as everything else seemed to crumble (over and over again). And so, a lot of the UK is in mourning. The Queen was not just some nice old lady; she was everything that once was: duty, integrity, substance, and gradualism.

The UK declared a period of national mourning. It was designed to reflect both the public mood and the gravity of the moment. It was a “time for reflection” and an appreciation of the new way of things. But, what does “national mourning” exactly mean? How does the UK compare to other famous examples in history?

To help us understand, here are 5 famous cases of national mourning.

The UK: Queen Elizabeth II

There are few “official” guidelines to the UK’s national mourning. In a liberal democracy, with as many views as people, there’s not much a government can do to “make” someone mourn (especially given that a substantial minority won’t care). The mourning period is expected to last around 17 days, culminating in the funeral of Elizabeth II on September 19 (which was declared a national holiday).

Many newsreaders and reporters will wear black during this time. Sporting and cultural events will be canceled or postponed. Regular TV programming will feature, predominantly, Queen-focused items. Normal government business — ministerial visits, policy announcements, press briefings, etc. — is on hold. There are official places all around the country to leave flowers or respects, not only around the royal estates, but also in parks, town squares, or famous locations. Flags will be flown at half-mast, a practice that goes back to the 17th century and often thought to leave a space for the “invisible flag of death.”

No business or school is “forced” to do anything, although special dedications are common, with posters, portraits, art, and poems being displayed. For the UK, “national mourning” is a private and discretionary thing. It’s unforced and freely offered up by loving people.

North Korea: Kim Jong-il

That’s not exactly what happens in North Korea. When the communist dictator, Kim Jong-il, died in 2011, the country declared a state of emergency, and all factories and companies called their employees into work. Even those abroad (mostly in China) were forced to return, en masse, to their home country to mourn. When there, they had to pay their respects to the nearest statue of the North Korean founder, Kim Il-sung (Kim Jong-il’s father). For how long and in what manner is subject only to what the media could access, with a lot of ostensible wailing and “writhing in pain.”

North Korea underwent 11 days of mourning, during which any kind of entertainment was banned. There was no drinking, joking, or joviality of any kind (at least in public, anyway). Politics was suspended, and people couldn’t leave the country (nor could foreign dignitaries enter). Ten years later, in 2021, national mourning was still serious business in North Korea. During the 11-day mourning period for the tenth anniversary of Kim Jong-il’s death, laughter was banned. And, in a country where falling asleep could mean death by artillery, it’s probably best not to crack a smile.

Various: King Hussein of Jordan

Like Queen Elizabeth II, King Hussein was viewed as a rock. He was the steady, unmoving pillar amid the tempest — not just in his home Jordan, but all over the Islamic world. As such, when he died from cancer in 1999, there was national mourning declared in countries from Egypt to Bangladesh. In Jordan, shops were shuttered and schools canceled. All business was halted for three days, and three months of Muslim mourning was declared.

The customary period of mourning for a relative in Islam is three days. By declaring three months, Jordan was bringing the death of King Hussein closer to that of a widow (who mourns for roughly four lunar months). It was a very public statement about just how they saw the 66-year old monarch. Islamic mourning practices allow weeping, but discourage loud, screeching displays of grief (unlike North Korea). For the widow, they involve dressing somberly, not wearing perfume, and only leaving the house for official and necessary business. For much of Jordan, as well as many Middle Eastern countries, the same was expected as they mourned King Hussein.

The Mongols: Genghis Khan

You and I might be speaking Mongolian right now, if it were not for the Mongols’ mourning practices. In the mid-13th century, there were few people who could even attempt to stand up to Genghis Khan’s armies, let alone beat them. The Mongols had defeated two of the biggest empires of the time: the Jin in China and the Khwarazmian in Central Asia. They had left a trail of rotting battlefields in Russia and Eastern Europe. By 1241, Genghis’ son, Ogodei Khan, defeated a coalition of Hungarians and Romanians, and his cavalries looked set to sweep across Europe.

But then, Ogodei died. Genghis Khan and Mongol tradition insisted that at the death of the “great khan,” all generals, important family members, and other minor khans had to return to oversee the burial of their leader. This meant that the leaders of the Mongols’ westward expansion had to ride roughly 3700 miles back home. Europe was saved. The Mongols did try again 40 years later, but by this time, Europe had regrouped and recovered. What’s more, the Mongols were a different (and slightly less brutally efficient) threat altogether.

The Vatican: Pope John Paul II

It probably comes as no surprise that the death of a pope is accompanied by pomp, ritual, and great gravity. When a pope dies, the body lies in St. Peter’s Basilica for nine days, during which time mourners can visit and pay respects. At the death of John Paul II, two million pilgrims passed by his corpse. The funeral of a pope must be held between fourth and sixth days of his death, and his body is usually (but not necessarily) buried beneath St. Peter’s. Then, comes the Conclave.

All the cardinals of the Catholic Church must gather together (locked in and with beds provided) to elect a new pope — not quicker than 15 days but not longer than 20. If a pope lives long enough, he can essentially appoint enough cardinals who agree with his doctrinal position to guarantee a like-minded successor. John Paul II, for instance, appointed all but two of 117 papal electors.

The world, especially the Catholic world, held great mourning ceremonies for John Paul II. His native Poland declared six days of mourning and Italy had three. Hundreds gathered to mourn his death on the Indonesian Island of Nias, only two days after an earthquake killed 1,300 people.

The death of a symbol

National grieving and state mourning practices can seem peculiar to outsiders. To people outside the UK, the grieving of one lady might seem over-the-top. To those who do not understand what a pope, cleric, king, or revolutionary means to a nation, the long and maudlin state of mourning seems almost farcical.

But when nations grieve for their famous and great people, they are not mourning a person. They are mourning a symbol. They are saying goodbye to a golden age or a nostalgic past. The death of a Queen Elizabeth or a Pope John Paul does not mark the end of one life; it marks the end of a time. At the very least, that’s pretty significant and, for most of us, often deeply sad.