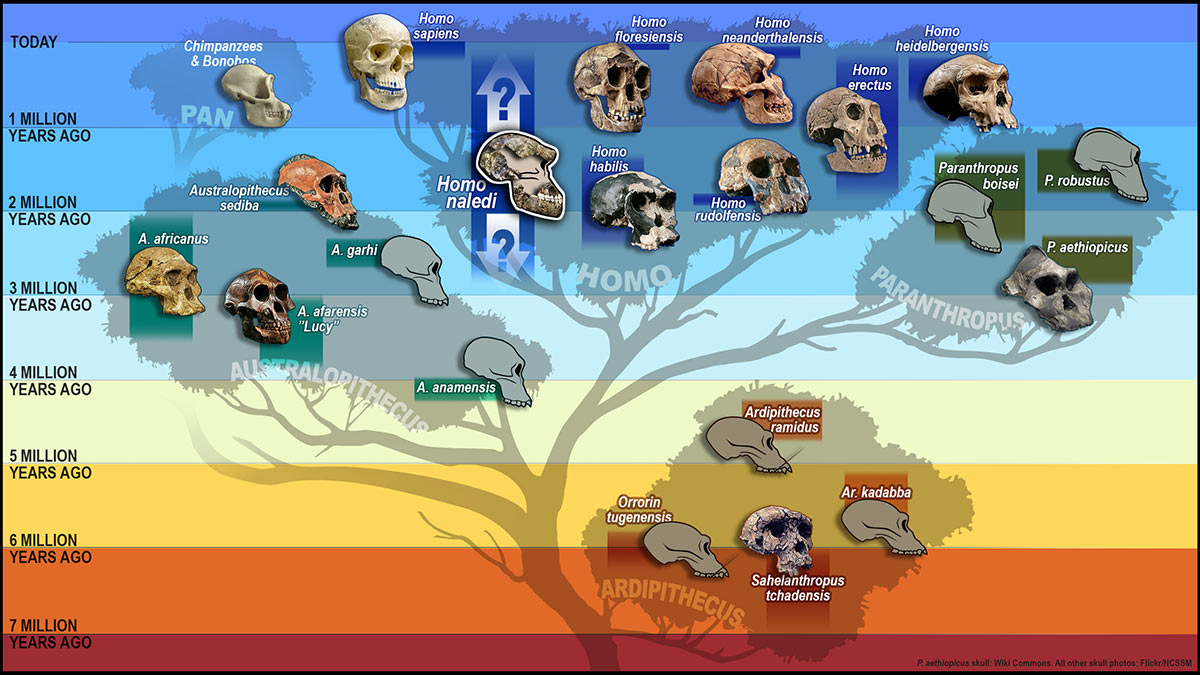

Homo sapiens is #9. Who were the eight other human species?

- Most experts agree that our species, Homo sapiens (Latin for “wise men”), is the ninth and youngest human species.

- The lives of the other eight species tell a story of how humans slowly evolved away from the other apes, developing the ability to walk, eat meat, hunt, build shelters, and perform symbolic acts.

- Our ancestors probably pushed our closest relatives, the Neanderthals, to extinction. Wise guys finish last.

We like to think humans are special. Certainly, our species has some impressive accomplishments compared to those of our closest living relatives, the chimpanzees and bonobos. Yes, these species fight, communicate, and use tools. But none developed a formal language, traveled space, altered the course of a planet’s climate, painted the Mona Lisa, composed Für Elise, conceived of the Internet, or invented Velcro.

It seems odd that our closest living relatives have such little ambition. (Though arguably, they have more peace — well, except for the Gombe Chimpanzee War.) Have you ever wondered why there is not another species like us?

One line of reasoning suggests that we would not be so unique had we not killed off some of our relatives.

The eight other human species

Around 6 million years ago, a branch of apes evolved to become the first species of the genus Homo. These early humans ditched the long arms of apes for stronger legs. While they could no longer swing around on trees, they could stand upright, walk, and colonize new ecosystems, away from the forest. The brains of early humans grew until we were using complex tools to hunt large animals, build fires, and construct shelters.

By the time Homo sapiens arrived on the scene some 300,000 years ago, we were the ninth Homo species, joining habilis, erectus, rudolfensis, heidelbergensis, floresiensis, neanderthalensis, naledi, and luzonensis. Many of these species lived for much longer periods of time than we have, yet we get all the attention. It is time for a family reunion.

H. habilis: the handyman (2.4 million – 1.4 million years ago)

In 1960, a team of researchers uncovered fossilized remains of an early human in Tanzania. These fossils had braincases slightly larger than those of apes. Suspecting that these specimens were responsible for the thousands of stone tools found near the site, scientists dubbed the species “handy man” — Homo habilis. Thought to have evolved nearly 2.4 million years ago, H. habilis is widely considered to be the first member of the genus Homo that evolved from apes.

H. Habilis was small, clocking in around 70 pounds and standing somewhere between 3.5 feet and 4.5 feet tall. We also know that H. habilis made complex tools, including stones used to butcher animals. H. Habilis lived as the only member of our genus for nearly a million years.

H. erectus: the enduring hiker (1.89 million to 110,000 years ago)

As the name implies, Homo erectus is the first known Homo species that stood fully upright. H. erectus featured other, modern human proportions distinct from those of apes: shorter arms relative to the torso, and long legs adapted for walking and running, rather than climbing trees.

H. erectus is the first human with a significantly larger braincase than that of apes. They also had smaller teeth. The latter adaptation probably helped H. erectus eat meat and quickly digestible protein. This would fuel the increased nutritional requirements that came with taller bodies and larger brains.

In fact, scientists found campfires and hearths near the remains of H. erectus, suggesting they were the first humans to dabble with cooking — a uniquely human activity that gave us access to easily digestible food, allowing our brains and bodies to grow.

H. erectus was a very successful species. They walked the Earth for a period lasting nearly nine times as long as our current reign.

H. rudolfensis: the stranger (1.9 million to 1.8 million years ago)

We know little about Homo rudolfensis, a hominid discovered near Kenya’s Lake Rudolf (now known as Lake Turkana). H. rudolfensis had a considerably greater braincase than Homo habilis — a good indicator that the species was human. However, some scientists argue it may be better placed with the genus Australopithecus, a close relative of Homo, because of its smaller size and similarities in the pelvis and shoulder.

H. heidelbergensis: the hunter (700,000 to 200,000 years ago)

Around 700,000 years ago, Homo heidelbergensis (sometimes referred to as Homo rhodesiensis) arrived on the scene in Europe and eastern Africa. Scientists think that these smaller, wider humans were the first to live in cold places.

The remains of animals like horses, elephants, hippopotamuses, and rhinoceroses, were found together with H. heidelbergensis. That proximity suggests that this group of humans was the first to hunt larger animals with spears. To stay warm, these humans also learned how to control fire, and they built simple shelters out of wood and rock.

Most scientists agree that the African branch of H. heidelbergensis gave rise to our own species, Homo sapiens.

H. floresiensis: the Hobbit (100,000 to 50,000 years ago)

Homo floresiensis is known only from remains found in 2003 on the Island of Flores, Indonesia. Along with the remains of H. floresiensis were some stone tools, dwarf elephants and komodo dragons — a discovery that paints quite a scene of the island life of these small humans.

The isolation of H. floresiensis likely contributed to its small brains and stature (estimated at approximately 3 feet, 6 inches from a female specimen). In fact, its size conforms to the ecological principle of insular dwarfism, which predicts that animals reduce their body size when their population’s range is limited to a small island environment. H. floresiensis made stone tools and hunted diminutive elephants, whose own small size stands as another example of insular dwarfism. How H. floresiensis arrived at its namesake island is still unknown — the nearest island is separated from Flores by 6 miles of rough seas.

H. neanderthalensis: The Neanderthal thinkers (400,000 – 40,000 years ago)

Say hello to our closest relatives — the Neanderthals.

Neanderthals were shorter and stockier than us but had brains that were as big, or even bigger, than our own. Neanderthals lived a tough life. We find bones riddled with fractures, suggesting they did not always succeed when they hunted large animals. They also lived in seriously cold environments in Europe and in southeastern and central Asia. To cope, they made fires and lived in sophisticated shelters. They also made clothing, using complex tools such as sewing needles crafted from bone.

Scientists have found dozens of fully articulated Neanderthal skeletons across many sites, which suggests that the Neanderthals buried their dead and marked their graves. This indicates that Neanderthals conducted the kind of symbolic acts associated with the cognitive processes that lead to language.

Their burials also helped modern humans: With so many intact specimens, scientists have successfully extracted Neanderthal DNA. Using that resource, researchers found that at one point, humans and Neanderthals mated.

H. naledi: the enigmatic newcomer (335,000 to 236,000 years ago)

Homo naledi were small hominids that lived in South Africa. We do not know much about H. naledi, because they were only discovered in late 2015. In a single expedition, scientists excavated an astounding 1,550 specimens from at least 15 individuals. These specimens show us that H. naledi were small (around 4 feet, 9 inches). While the excavation unearthed a treasure trove of human fossils, the researchers found no tools or other animals alongside H. naledi, so their lifestyle remains a mystery.

H. luzonensis: a polemic finding (at least 67,000 years ago)

In 2019, researchers visited a small cave on an island in northern Indonesia. Inspired by the discovery of H. floresiensis, the scientists wondered whether other islands also had human dwellers. The researchers struck gold — kind of. Though they found human remains, they only unearthed seven teeth, three foot bones, two finger bones, and a fragment of a thighbone. Still, due to its geographic isolation and small size, the scientists felt confident in declaring that this species was unknown to science. They named it luzonensis after Luzon, the island on which it was found.

Some researchers question the finding, arguing that there were not enough remains to rule out that H. luzonensis is a variant of the well-known island-dweller H. floresiensis. The discovery reinvigorated questions of how exactly these humans reached the islands.

Wise guys finish last

Not all these extinct humans coexisted with our H. sapiens ancestors. Most of them probably went extinct due to intense changes in climate.

However, scientists suspect we were hardly friendly with species such as H. neanderthalis that did live alongside us. After humans moved into Europe, Neanderthal numbers began to dwindle. Since we all know what humans are capable of — great acts of mercy, but also of war and violence — we do not really need to guess at what happened. We competed for space and food, and we outmatched our closest relatives. The fact that they held on for so long suggests the tides could have turned easily against us.

Neanderthals left their mark in our DNA

Our enemies were also, evidently, our lovers. Scientists extracted some DNA from Neanderthal specimens and demonstrated that H. sapiens and H. neanderthalis mated; in fact, the genomes of modern humans include 1% to 8% Neanderthal DNA.

The Neanderthals are not alone in leaving their mark on our genetic blueprint — some of us might share DNA from archaic humans discovered in the Denisovan Cave in Siberia’s Altai mountains. Though we do not have enough remains to describe species in the Denisovan group, scientists managed to collect DNA from a juvenile female finger bone. Most scientists suggest that the Denisovans suffered the same fate as Neanderthals: They were outcompeted by our ancestors, but only after sharing ancient beds.