In ancient Rome, only one person was more powerful than the emperor

- The constitution of the Roman Republic allowed for an all-powerful dictator to lead Rome in times of crisis.

- Most dictators are remembered not for their accomplishments but for their admirable displays of self-restraint and obedience to the Roman Constitution.

- More than a century after the office was abandoned, a general called Sulla named himself dictator and paved the way for Julius Caesar.

After the people of ancient Rome expelled the despotic Tarquinius Superbus in 509 BC, they vowed never again to serve another king. Reassembling the remnants of their kingdom into a republic, Tarquinius’ traumatized subjects adopted a constitution whose checks and balances would prevent power from concentrating in the hands of any individual.

Instead of one king, the Roman Republic was ruled by two consuls. These consuls were nominated by the Senate and chosen by the Comitia Centuriata, a popular assembly. Each consul could veto the other’s decisions. Both were dependent on the Senate to implement their executive orders. The largely patrician (ruling class) Senate, meanwhile, had to contend with the tribunes of the plebs (citizens acting in an official governing capacity).

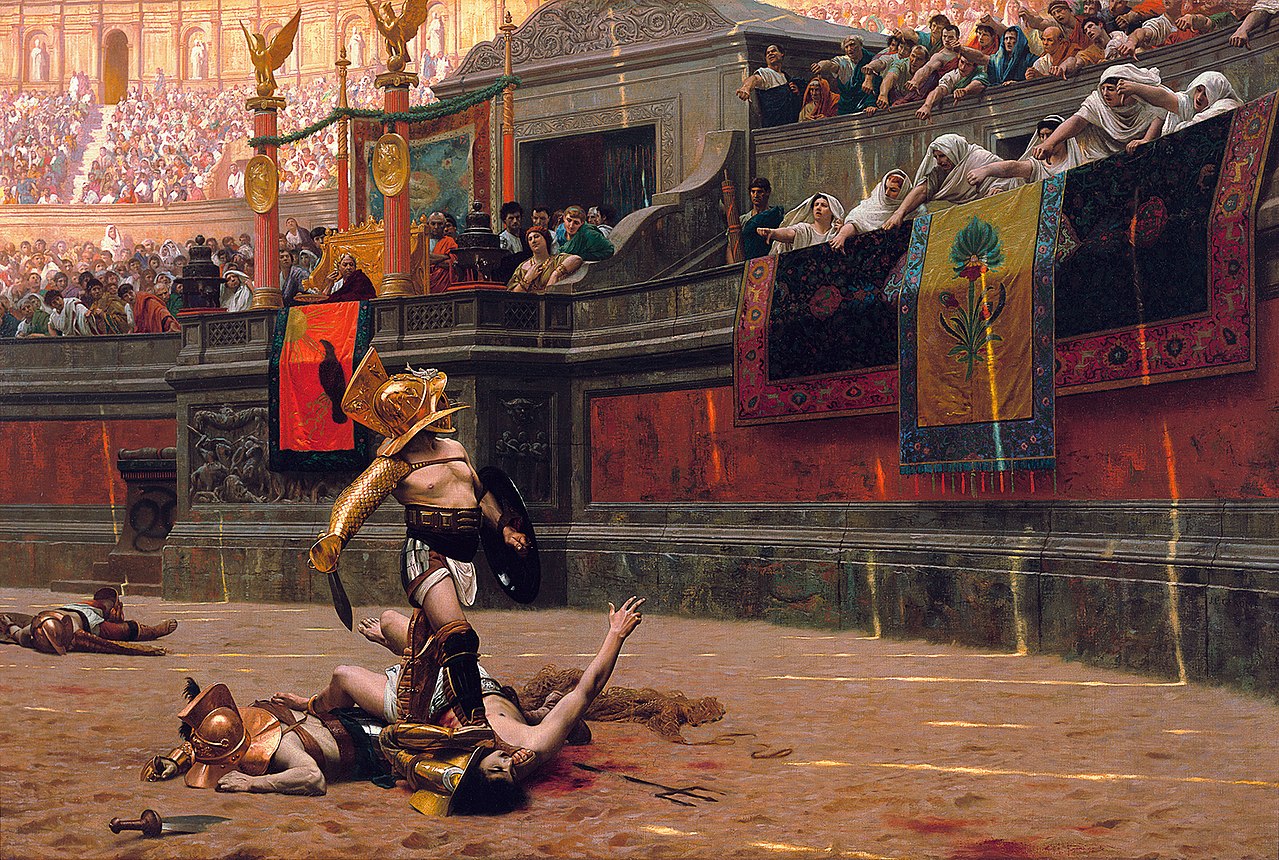

The only weakness in this setup was revealed during national emergencies, which called for quick, decisive action as opposed to unending debate. To help the Republic defend itself in times of crisis, its founders created guidelines for appointing temporary dictators who, while in charge, stood head and shoulders above the senators, consuls, and even Rome’s old kings.

One could even argue that Rome’s dictators were more powerful than its emperors. Constitutionally, the emperor and the Senate were considered equals, with the latter absorbing the duties and responsibilities of the people’s tribunes. Unlike dictators, emperors also lived at the mercy of soldiers, with Commodus, Caracalla, and Elagabalus dying at the hands of their own bodyguards: the Praetorian Guard. After Constantine, Rome’s emperors were further constrained by the principles of Christianity.

Unlimited power for a limited time

True to his name, the dictator was the most powerful person in the Roman Republic. His decisions could not be vetoed or appealed by the other branches of government, leaving him free to conscript soldiers, plan military campaigns, or persecute enemies of the state. Crucially, dictators could not be held accountable for their actions after their six-month term expired.

Between 501 BC and 202 BC, Rome saw approximately 85 dictatorships. Dictators were the only magistrates in Rome who were appointed rather than elected. Candidates were typically picked by consuls in collaboration with the Senate, though there also have been cases in which dictators were appointed by the Comitia Centuriata instead.

There were many reasons for appointing a dictator. Some, like Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus (the namesake of the American city Cincinnati) and Marcus Furius Camillus, were appointed when the Republic was at war with foreign powers. Others, including Quintus Hortensius, entered office to control domestic conflicts between the patricians and plebeians.

Dictators were also appointed to fill in for the consuls. In 257 BC, Quintus Ogulnius Gallus became dictator to lead a religious festival in honor of Jupiter while the incumbent consuls were fighting in the First Punic War. During the Second Punic War, which lasted 17 years, the Roman Republic repeatedly appointed dictators to oversee elections.

The dictatorship and faith

Rome’s greatest dictators are less remembered for their accomplishments than their admirable displays of self-restraint and obedience to the law. Throughout his life, Lucius Camillus was named dictator five times. Time and again he respected the term limit, returned his borrowed authority to the consuls and the Senate, and retired to his countryside estate as an ordinary citizen.

Camillus’ actions were informed by experience. He had, after all, personally witnessed the tyranny of Tarquinius. The same cannot be said for his eventual successor Cincinnatus, who holds a special place in Roman memory for honoring the code of the Republic despite being born sometime after its establishment and having no personal recollection of the last king’s deposition.

“How is it possible,” asks the historian Marc de Wilde, “that, until the first century BC, the Roman dictatorship was never abused and turned against itself?” Previous scholars have pointed to formal constraints such as the six-month term limit, but this argument is not convincing, considering that dictators could — and often did — make changes to the Republic’s constitution.

In her book States of Emergency in Liberal Democracies, Nomi Claire Lazar makes the simple yet bold claim that the office of dictator was successful because dictators always acted in good faith. Such behavior, De Wilde elaborates, was ensured by informal restraints like peer pressure as well as moral and religious responsibility.

Roman dictatorship disintegrates

Although dictators repeatedly saved the Roman Republic from destruction, the office had its critics. Fearing the patrician Senate might someday use a dictator to oppress civil liberties, the Comitia Centuriata campaigned for the right to appeal a candidate’s nomination. This made the appointment process more democratic, but also slower and less effective.

While Camillus and Cincinnatus enjoyed near-limitless power, future dictators faced an increasing number of constraints. In the late Republic, they had to depend on the Senate for financial support. They were also barred from exercising their power outside Italy, a major setback for the office as Rome extended its influence across the Mediterranean.

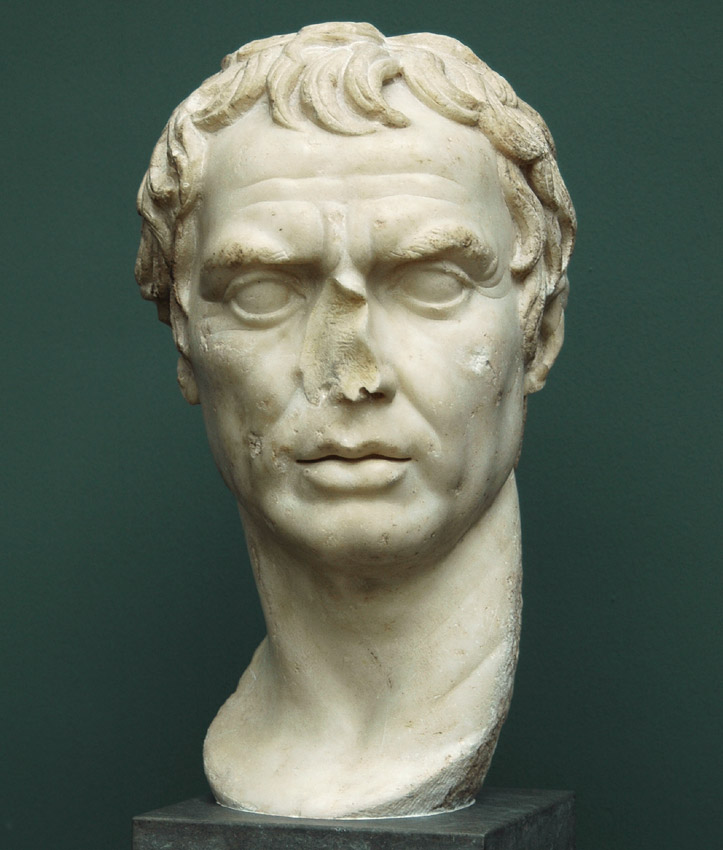

For these and other reasons, the office slowly fell into disuse until, more than 100 years after the last dictatorship, it was revived by the general Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Sulla had emerged as the victor of a ten-year-long civil war. As conventional dictator, he used his power to crush opposition as well as reinforce the constitution to prevent future infighting.

Though he had appointed himself and served for three years instead of six months, Sulla resembled previous dictators insofar as he stepped down once his original task — in his own words, “to write the laws and to restore a constitution to the state” — had been completed. Leaving the Republic in the hands of duly elected officials, he too retired to live in the countryside.

From dictator to emperor

If acting in good faith is considered the primary characteristic of Roman dictatorship, Sulla cannot be considered a dictator. Sulla’s rule, as Theodor Mommsen writes in Roman Constitutional Law, “has nothing in common with the older [dictatorships] apart from the name and several outward appearances.”

Sulla — and, by extension, the dictatorship itself — are responsible for ending Roman republicanism and paving the way for the Roman Empire insofar as they set a political precedent for Gaius Julius Caesar, who in 44 BC proclaimed himself dictator perpetuo or “dictator in perpetuity.” He held this title until he was assassinated by the Senate a month later.

Ignoring Caesar and Sulla, though, the fact remains that most dictators remained loyal to the constitution that granted them their power. Thanks to them, the Roman dictatorship is now regarded as a remarkably successful form of emergency government.