Archaeologists discovered what they thought was an ancient synagogue. They were wrong.

- What was long thought to be an Israeli synagogue bears more resemblance to Roman temples from Syria.

- The temple may have been erected to strengthen the Roman presence in Judaea.

- Ancient structures in Israel are notoriously difficult to study because the region has been occupied by many different cultures over the centuries, most of which have worked hard to erase the traces of each other’s existence. The vandalism continues to this day.

In 1991, archaeologists discovered the ruins of a 4,000-square-foot structure in Beit Guvrin-Maresha National Park in central Israel.

The first thing they tried to determine was who built it and for what purpose. Israeli archaeologist Tsevi Ilan argued the structure was a synagogue — one of the earliest ever created — because of its resemblance to various Late Roman synagogues found in northern Israel. This idea, developed in an untranslated text titled Bate-keneset ḳedumim be-Erets-Yiśraʼel, remained uncontested until archaeologists came back to reexamine the structure in 2015.

One of these archaeologists, an associate professor from the University of British Columbia named Gregg Gardner, has come to doubt Ilan’s theory. This is not only because his team was unable to find any Jewish iconography such as menorahs, for instance, but also because — as he recently explained to Israeli newspaper Haaretz — “neither the layout of the structure nor decorations indicate it might have been a synagogue.”

At second glance, the structure looks less like a synagogue from northern Israel and more like a Roman temple from southern Syria. Communicating to Big Think via email, Gardner and his colleague Orit Peleg-Barkat, a professor at Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Institute of Archaeology who served as co-director of the excavation, explain why:

“(1) The structure is built on a square podium more than two meters above the surface level outside of the edifice in a prominent topographic location;

“(2) It has a paved forecourt and a rectangular chamber on the side farthest from the entrance;

“(3) The forecourt is surrounded by an ashlar-built wall;

“(4) Cornices, an acroterion, and a rounded niche-head, attest to the ornamentation of the original building and its grandeur;

“(5) It has an axial and symmetrical plan with an approximately east-west alignment; and

“(6) It has a single main façade, and the structure is accessed from only one direction, via an impressive staircase.”

“These features,” Gardner and Peleg-Barkat surmise, “are more characteristic of what we know of Roman temples than synagogues or other structures from this era in the region.”

The possible origin of the Roman temple

While Gardner and Peleg-Barkat’s thesis is more convincing than Ilan’s, it has yet to be confirmed. Just as the archaeologists have been unable to find any Jewish iconography, so have they been unable to find any Roman iconography. And it is unlikely the mystery will be solved anytime soon. Ancient structures in Israel are notoriously difficult to study because the region has been occupied by many different cultures over the centuries, most of which have worked hard to erase the traces of each other’s existence.

Luckily, we do have some understanding of the chronology of human settlement in Israel. Following the death of the Macedonian conqueror Alexander the Great in 323 BC, his generals vied for control of the strategically placed Holy Land. Israel passed from the Ptolemies of Egypt into the hands of the Seleucid king Antiochus III who, according to ancient historian Flavius Josephus, granted his Jewish subjects religious and civil liberties in exchange for loyalty.

The presence of Hellenistic Seleucids in central Israel is reflected in the region’s diverse archaeological record. In 2005, reports Haaretz, tourist-diggers at Maresha stumbled upon a broken stone slab with Greek inscriptions. Other artifacts of Hellenistic origin, including pottery shards and the head of a zoomorphic figurine, have also been recovered from the park.

During the last years of his reign, King Antiochus waged a brutal war against the expanding Roman Republic, but was defeated at the Battle of Magnesia around 189 BC. Israel would be officially incorporated into the Republic a century later as the province of Judaea. Its inhabitants, oppressed politically as well as religiously, resisted Roman rule through a series of three military uprisings.

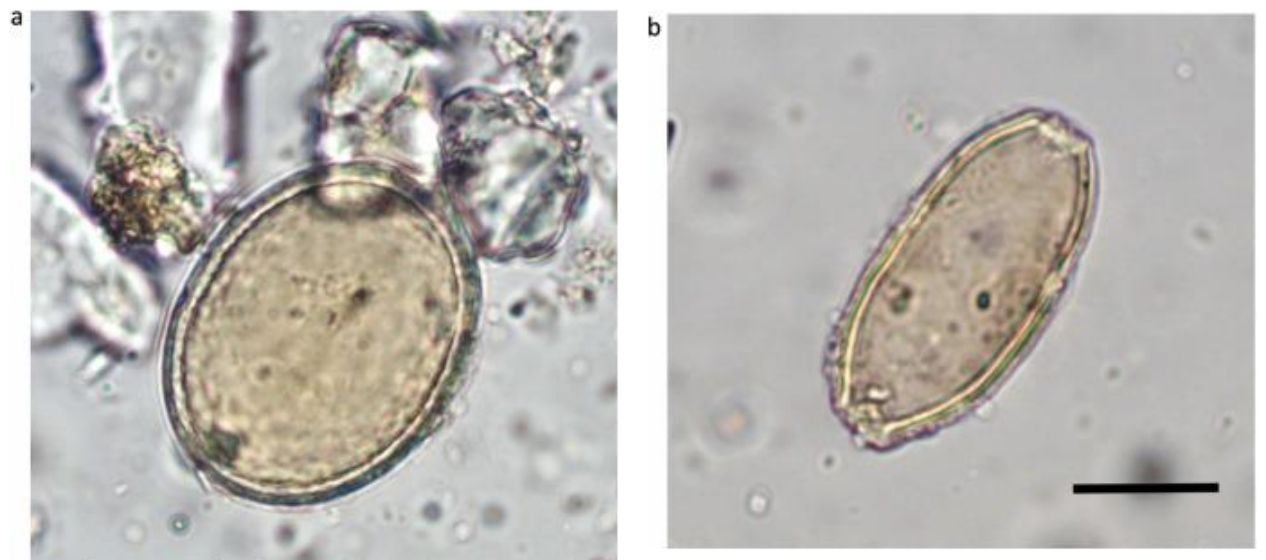

Peleg-Barkat suspects that the Roman Temple at Beit Guvrin-Maresha may have been established during the last and most significant of these uprisings: the revolt led by Bar Kokhba in 132 AD. According to the historian Cassius Dio, the revolt led to the deaths of half a million Jews and the destruction of close to 1,000 Jewish villages in the province. A 2019 study published by Peleg-Barkat found that the region around the temple was heavily populated by Jewish communities prior to the revolt, reiterating the extent to which their war with Rome affected them.

Citing Gardner and Peleg-Barkat, Haaretz writes that the temple might have been “erected by the Romans in defense of the Bar Kokhba revolt” and “likely doubled as a symbol of the Romans’ victory and a message warning the former Jewish occupants not to return.”

Archaeological vandalism in central Israel

Hopefully, the archaeologists will be able to further investigate their theories. More than one excavation in central Israel has been abandoned thanks to robberies and vandalism. Every year, local newspapers publish reports of thieves slipping into poorly guarded sites and making off with priceless artifacts. (Last year, a family with children pretending to have a picnic were caught looting underground Roman warehouses at Horvat Zaak.)

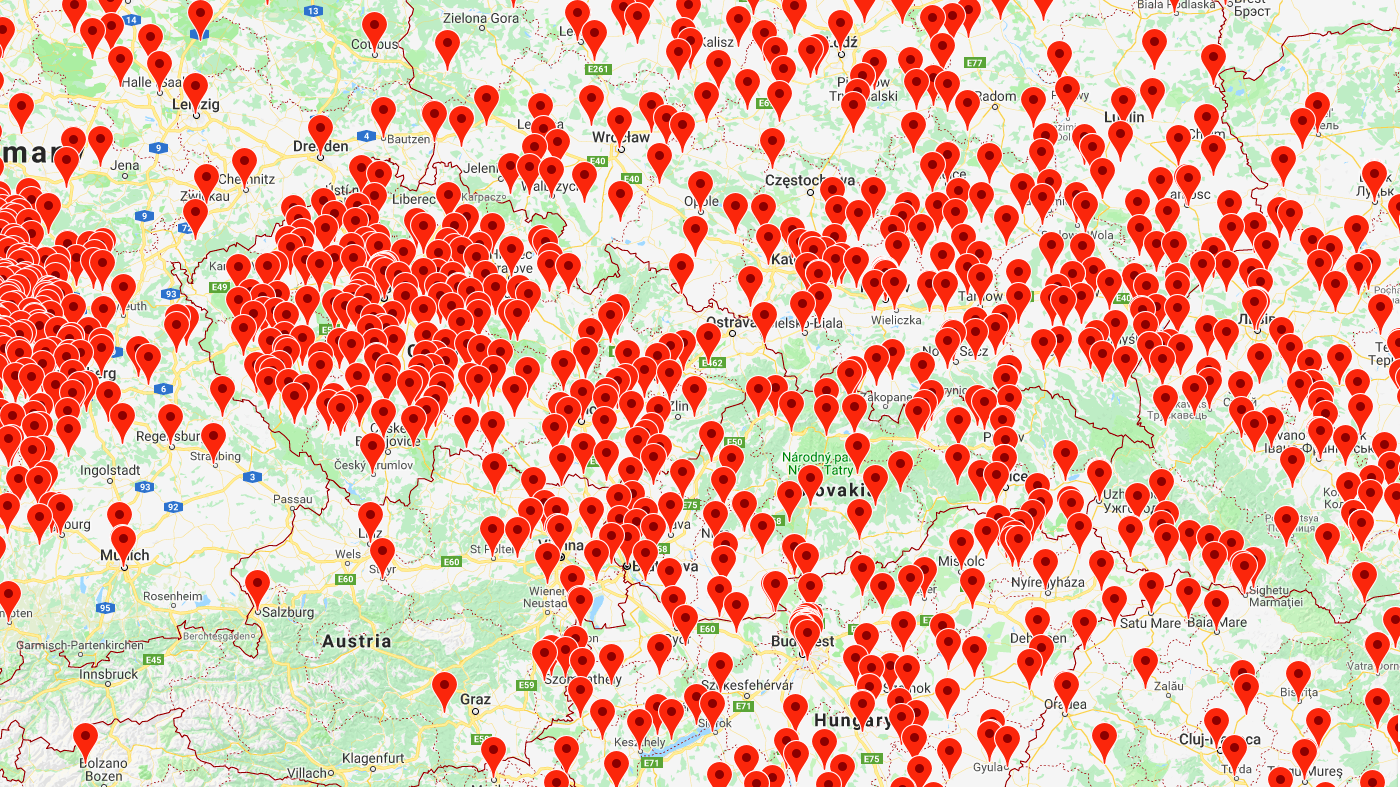

Vandalism is common, too — so common, in fact, that Gardner and Peleg-Barkat refused to disclose the precise location of the structure to Haaretz. (The temple, they told Big Think, is actually located closer to Horvat Midras than it is to Beit Guvrin-Maresha National Park.)

In Israel, archaeological sites are often defaced because they are of religious or cultural significance. In 2012, vandals covered a 4th century synagogue at Hammath Tiberias with graffiti reading, “To Shuka the cannibal,” in reference to Shuka Dorfman, the director of the Israel Antiquities Authority, a government agency regulating excavation and conservation projects. The vandals also destroyed mosaics and panels depicting menorahs.

In his article, “Pagan Images in Late Antique Palestinian Synagogues,” UCL Jewish studies professor Sacha Stern observes that “similar evidence of iconoclasm has been discovered in contemporary Palestinian churches” in Beit Guvrin National Park, where the human faces of mosaics have been “selectively erased and replaced with patternless arrangements.”

Archaeologists hope that the Roman temple, which still holds many unsolved mysteries, will not succumb to such a fate.