The case for resurrecting the lost world of collective bathing

- Bathhouses were a cornerstone of Roman civilization, equalizing its stratified society.

- These “Thermae Romae” were more than swimming pools: They also contained saunas, exercise courts, and even libraries.

- In our alienated modern world, a culture of collective bathing might be one way to help address loneliness.

In 2008, the Japanese comic book artist Mari Yamazaki began working on a manga called Thermae Romae. Published the following year, it’s set in ancient Rome and follows a Roman architect named Lucius. Tasked with designing a bathhouse, or thermae, Lucius struggles to come up with new ideas — until he discovers a secret tunnel in his neighborhood spa that inexplicably leads him to a bathhouse located in modern-day Japan.

Almost every chapter has the same structure: Lucius runs into a creative block and decides to take a break. Once in Japan, he encounters a variety of technologies, mechanisms, and designs that he, upon returning home, implements in his own projects. You’d expect that a story revolving around such a niche topic would also have a niche audience, but nothing could be further from the truth. Upon its release, Thermae Romae became a smash hit — not only in Japan, where a culture of collective bathing persists to this day, but also in the West, where luxury spas and wellness movements help scratch a similar itch, especially among young people.

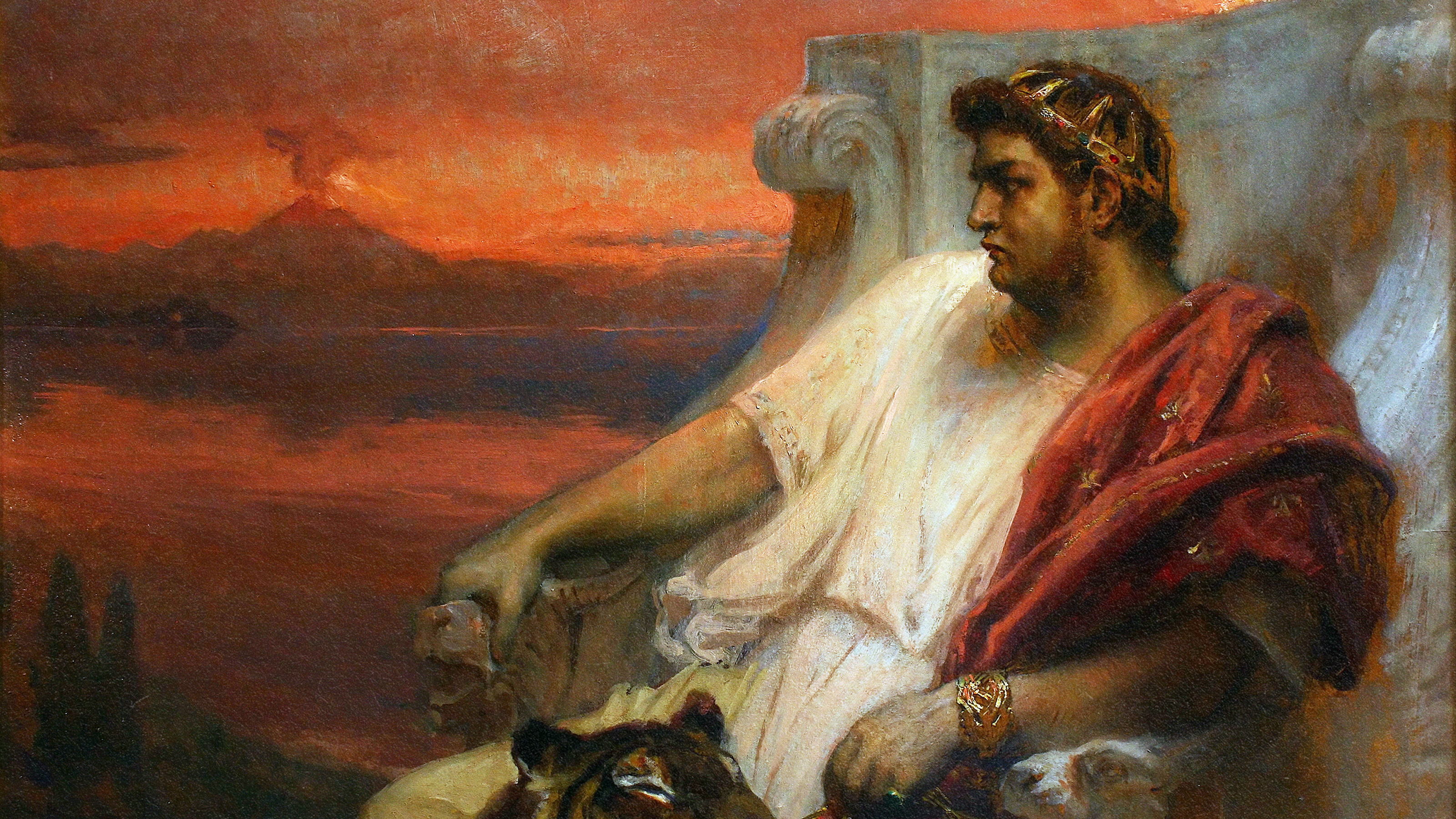

The international success of Thermae Romae raises an important point. When considering the legacy their societies inherited from ancient Rome, most scholars focus on the gladiatorial games and republican institutions. Often ignored are Rome’s countless baths. Although largely abandoned by the Western world today (more on that later), public bathing was a cornerstone of Roman civilization. The first thermae predates the construction of the Colosseum by several centuries, and they outlived the transition from republic to empire, by which time many other traditions had disappeared.

The baths even survived the fall of Rome itself, continuing to operate into the Early Middle Ages. But what about these places made them so resistant to historical change? As it turns out, there’s a lot more to them than rest and relaxation. To some extent, Roman baths aren’t even about bathing.

A day at Thermae Romae

The oldest of the Thermae Romae date to the 2nd century BC, and they increased in both size and numbers as time went on. In 33 BC, the number of baths in the Eternal City alone had risen from a handful to more than 170. By the early 5th century AD, that quantity had climbed to an astounding 856.

Though many baths — especially those in towns and suburbs — prioritized form over function, the most impressive of them were architectural marvels. The greatest of the greatest, the Terme di Caracalla — named after the emperor who financed their construction — rivals the Forum and Pantheon in scale and opulence. Spanning 11 hectares, the complex seems to have been capable of accommodating as many as 2,500 guests. Decorated with mosaics and statues, its purpose was not just to improve people’s quality of life, but also to offer access to aesthetic experiences that had been hitherto reserved for the elite.

Roman baths were also marvels of engineering. Water, carried over by aqueducts, was heated by furnaces before being funneled into various pools. Those same furnaces also warmed the building’s floors and walls, offering ancient Romans all the comforts of a modern spa.

Versatility was the name of the game, with even the smallest public baths sporting at least three different pools: a tepidarium or warm pool; a caldarium or hot pool; and, finally, a frigidarium or cold pool. Medium-sized thermae also featured steam rooms (called sudatoria) and laconica: hot dry rooms similar to saunas that, according to the architect Vitruvius, regulated their temperature by lowering a brazen shield over a small opening in the roof. The biggest thermae — like the Baths of Caracalla — went even further, offering outdoor courtyards (called palaestras) where people could hang out or exercise, as well as gardens and libraries. While the preferred sports varied from one Italian region to another, common palaestra activities included boxing, wrestling, discus throwing, and weightlifting. With so many different things to do, it should be no surprise that many Romans went to the baths on a daily basis and stayed there for several hours at a time.

Most of what we know about Roman baths comes from written sources. However, archaeological evidence can give us an even clearer picture of what went on inside these places. Here, the evidence includes not only the remains of the baths themselves, but also the objects that researchers have been able to recover from their occasionally intact draining systems. Digging through the sewers of Roman settlements in Italy, Portugal, and Switzerland, archaeologist Alissa Whitmore stumbled across an array of hygiene products like perfume vials, nail cleaners, and oil flasks. She also recovered scalpels, needles, and food scraps, suggesting some baths may have been fitted with medical facilities, textile workshops, and food stands.

Roman bathing culture did change somewhat as the centuries went on. Take, for instance, the separation of genders. In the Republic’s early days, men and women commonly bathed together in the same physical space. Later, bathing rules changed to reflect evolving social norms. Although there were some baths that offered separate facilities for both sexes — the Stabian and Forum baths being noteworthy examples — men and women mostly adopted different bathing hours.

The joys of collective bathing

While Western countries inherited many customs and practices from ancient Rome, collective bathing isn’t one of them. With the exception of Sweden and Hungary, most people in Europe and the United States treat bathing as a private and practical act, as opposed to a public, symbolic one: It is something you do at home by yourself rather than outside and in the company of others.

While there’s nothing wrong with showering by yourself — especially from a hygienic perspective — there’s something to be said about the emotional and psychological benefits that bathhouses provide. As noted by the researcher Jamie Mackay in an article for Aeon, the transition from communal to private bathing mirrors the larger transition from “small ritualistic societies to vast urban metropolises.” And while big cities provide many valuable and at times life-saving services and commodities, the modern metropole has also opened the door to conditions like anxiety, depression, and alienation — qualms collective bathing coincidentally helped to remedy.

“It is difficult to imagine a more powerful counter-image to the dominant picture of modernity than the archetypal bathhouse,” Mackay writes.

“The Japanese sento, with its strict rules and fastidious emphasis on hygiene, could hardly be more different from the infamously squalid wash houses of Victorian Britain. Hungary’s vast fürdő, some of which spread over several floors, provide a different emotional experience to the intensity of the lakȟóta sweat-lodge of Native America. What links all these examples, however, is the role such spaces have in bringing together people who might otherwise remain separate, and placing them in a situation of direct physical contact. It is this aspect of proximity that remains significant today.”

In stratified Rome, collective bathing had an equalizing effect. As mentioned earlier, facilities like the Baths of Caracalla gave citizens of every economic class access to exercise, entertainment, and self-improvement, not to mention cleanliness. Even some emperors, albeit escorted by bodyguards, could be found bathing alongside ordinary plebeians. But the value of the Thermae Romae, writes Mackay, goes even deeper:

“Directly experiencing other real bodies, touching and smelling them, is also an important way of understanding our own bodies which otherwise must be interpreted through the often distorted, sanitised and Photoshopped mirrors of advertising, film and other media (…) Living in a society where actual nudity has been eclipsed by idealised or pornographic images of it, many of us are, independently of our will, disgusted by hairy backs, flabby bellies and ‘strange-looking’ nipples. The relatively liberal attitude towards such issues in countries such as Denmark, where nudity in the bathhouse is the norm, and in some cases mandatory, exemplifies how the practice might help renormalise a basic sense of diversity and break through the rigid laws that regulate the so-called ‘normal body.’”

For these reasons and others, Rome’s long-lost culture of collective bathing is sorely missed today.