Today’s dictators are united — but not by ideology

- Autocracy, Inc. explores how today’s autocracies differ from their 20th-century predecessors.

- Journalist and historian Anne Applebaum defines these regimes by their single-minded, nonideological determination to preserve their wealth and power.

- To combat Autocracy Inc., Applebaum argues that the world’s democracies should form a coalition of their own.

The germ of the idea that would eventually turn into Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and historian Anne Applebaum’s new book, Autocracy, Inc.: The Dictators Who Want to Run the World, came to her on a 2020 trip to Venezuela, a country long plagued by dictatorship, economic collapse, and mass migration.

“Venezuela was once the wealthiest country in South America,” Applebaum tells Big Think. “Now it’s the poorest, and you can see the destruction of the last 20 years everywhere you look. Given the degree to which the government operates against the interests of the nation, you have to ask, where is all power coming from?” The answer, though unclear to most foreign observers, is common knowledge among Venezuelans: not from President Nicolás Maduro himself, but a global network of autocratic states offering military and financial support.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that the current Venezuelan government is closely tied to other communist regimes, such as Cuba, Nicaragua, and China. Far more puzzling, at least at a glance, are its strong relations with countries like Russia, a failed democracy turned Christian nationalist neo-empire under the leadership of Vladimir Putin, or Iran, an Islamic theocracy. “Venezuela is on the other side of the world and does not share a common history or culture with these countries,” Applebaum says, yet their regimes are working together to keep Maduro in charge.

Venezuela’s far-reaching foreign relations bear little resemblance to the geopolitical landscape of the Cold War when much of the globe was divided between like-minded communist dictatorships with planned economies and liberal democracies with free markets.

“Unlike military or political alliances from other times and places,” Applebaum writes in Autocracy, Inc., “this group operates not like a bloc but rather like an agglomeration of companies, bound not by ideology but rather by a ruthless, single-minded determination to preserve their personal wealth and power; Autocracy, Inc.”

In the following interview, Applebaum — who, as one reviewer notes, began warning of the danger of post-communist Russia and the need for NATO’s expansion as early as the 1990s — explains how this new form of autocracy emerged, why Western democracies failed to anticipate its evolution, and what (if anything) could be done to stop Autocracy, Inc. from taking over the world.

Beyond ideology

Although today’s autocracies are by no means devoid of ideology — think, for example, of the centrality of Russkiy Mir in the Kremlin’s war against Ukraine, or China’s recent crackdowns on free enterprise and “bourgeois liberalization” — Applebaum argues that relationships between autocratic states are no longer based on ideological factors.

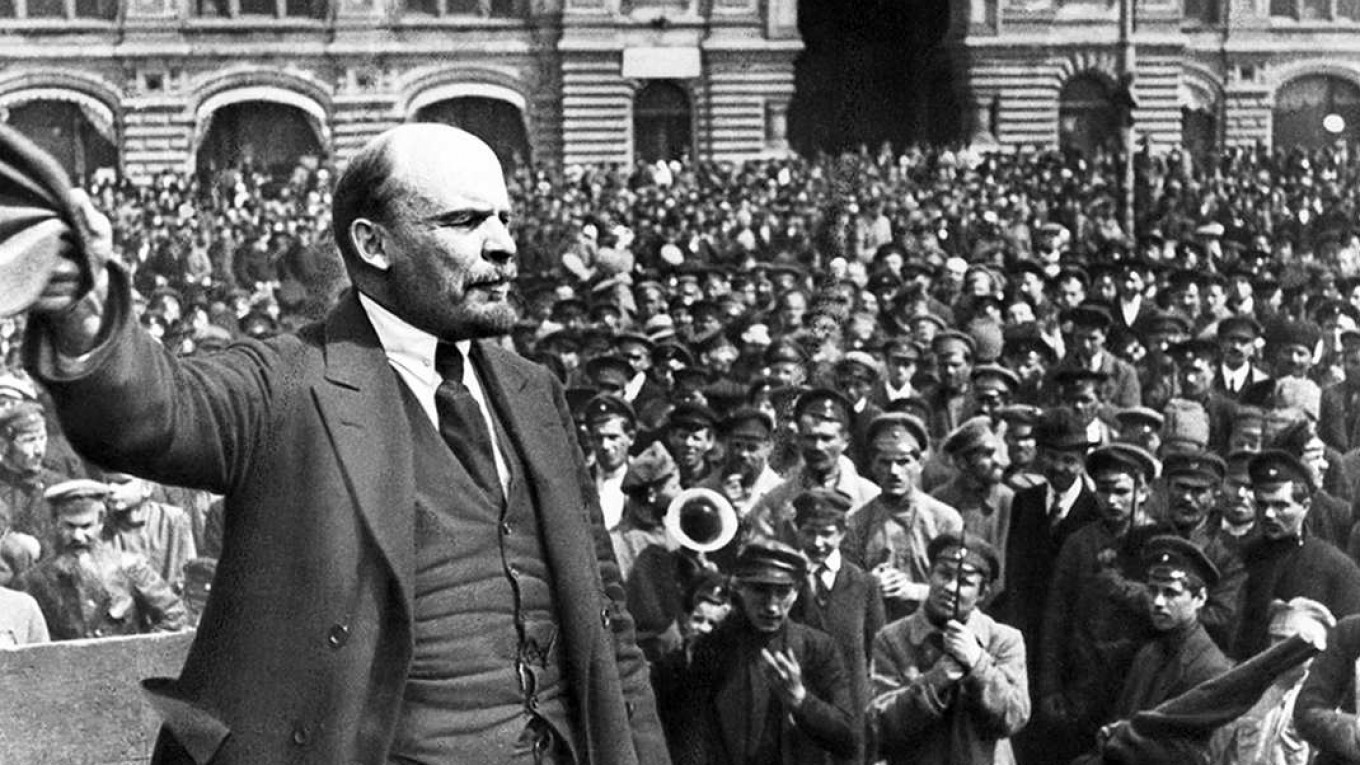

“The Soviet Union and the Soviet satellite states of Eastern Europe used the same language and had similarly constructed social systems,” she tells Big Think. “The Polish Communist Party, for example, was a copy of the Soviet Communist Party.” Even if they weren’t completely identical, they “nevertheless operated under a single banner and claimed to have the same goals. When we talked about the Soviet Bloc, we saw ourselves as fighting one thing.”

In contrast, the autocracies working together today don’t claim to be fighting for the same cause.

“The Iranians are fighting for an Islamic Middle East, the Chinese claim not to be imperialists at all, and the Russians are reconstructing an empire,” Applebaum says. “They are very different in what they say they’re doing. Some of them are one-man states, some have a ruling party, and some are ruled by a corrupt elite, like Venezuela.”

While some historians question the extent to which Soviet leaders actually believed the Marxist-Leninist propaganda they were spreading, they certainly wanted others to believe they did. The USSR “made a lot of effort to show itself to the rest of the world as building a communist utopia, even if — in practice — that was far from the truth.”

If today’s autocracies have anything in common, it’s their identification of a common enemy: the US, the EU, and NATO. In short, the “free” world and its purportedly liberal, democratic, and humanistic values. But while autocrats like Putin and Xi Jinping often claim to be engaged in a metaphysical war over the future of the civilization, Applebaum argues that their hostility towards “Western” concepts like feminism, fair elections, and an independent judiciary isn’t driven by an underlying philosophy so much as a practical and decidedly anti-intellectual desire to hold onto absolute power.

“It’s all empty window dressing,” she says, pointing to Russia — which Putin, in his battle against Western wokeness, passes off as overwhelmingly White and Christian — as an example. “Actually, Russia has very high divorce rates. Very few Russians go to church […] It’s also very multicultural, maybe even more so than Europe or the US, with a large percentage of Muslims. There’s an entire republic inside Russia: Chechnya, whose legal system is based on elements of Sharia law. The idea that Russian society represents some kind of pure, traditional system for White Christians is an absurdity.”

Speaking of Russia: While it’s no longer the world’s most powerful autocracy — that’s arguably China, for its larger economy, military capabilities, and global influence — the nation has played a large role in writing the modern autocratic playbook, introducing strategies that other autocracies (including China) went on to adapt.

“Russia had a Soviet legacy to build on,” Applebaum responds when asked how the country’s current regime came into being, and why it functions the way that it does. “The fact that Putin is a former KGB officer and has built a state based on people who were trained by the KGB did give them a particularly paranoid and cynical outlook on the world.”

As a result, “Putin is not someone who believes societies should be self-organized. He thinks all social activity and movement should be coordinated from the center. He’s not someone who can imagine a legitimate democratic opposition. For him, any opposition is by definition a foreign agent.” While the rise of Putinism was not inevitable — a different politician might well have steered Russia towards the democratic future many Russians were expecting after the USSR’s collapse — “once Putinism began, the fact that it took this form is maybe not surprising,” given the person he is and the environment that molded him.

Wandel durch Handel

For much of the Cold War, sanctions and censorship minimized contact between the two sides of the Iron Curtain. In the 1980s, when the construction of transcontinental gas pipelines opened up the possibility of restoring trade relations, European politicians like the West German Chancellor Willy Brandt argued that business with the USSR and its satellites would not just lead to the export of Western commercial goods but also democratic values.

Brandt’s policy — summarized by the slogan Wandel durch Handel or “Change through Trade” — gained momentum after the Cold War when much of the Western world believed it was only a matter of time before the communist bloc would adopt the victorious political and economic system of its rival.

“During the nineties,” Applebaum says, “people believed democracy would spread, and they had reason to believe it. It’s what happened in Europe after the Second World War when there was a concerted effort to create economic ties, which in turn led to political relationships and the spread of democracy to Western Europe, including Portugal and Spain, which were not initially democratically run.” After 1989, the European experience also worked out for Central Europe, which saw the adoption of liberal democracy in Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and the Baltic States.

“But while this was not a completely fake or false idea,” Applebaum continues, “I think we neglected the notion that, once you have a global information system, that influence can also go the other way. Putin’s rise to power took place in conjunction with money laundering schemes that were conducted with the help of Western financial institutions.”

Over the years, the Kremlin has not only suppressed anti-corruption and pro-democratic movements within Russia but also sought to export its agenda to other countries by way of TV channels and websites promoting misinformation. While the effect of these media operations is difficult to measure, there is no doubt that the US and Europe are currently experiencing a surge of political movements threatening to turn their struggling democratic governments into interns of Autocracy, Inc. The increasing popularity of figures like Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen, and Giorgia Meloni, not to mention the democratic backsliding of countries like Hungary, Brazil, and Israel, suggests that Handel durch Wandel has worked, just not necessarily in the direction that Brandt hoped it would.

Stopping Autocracy, Inc.

However endangered the future of American democracy may be at the moment, Applebaum insists the country has not yet stooped to the same level as Russia or the other regimes that make up Autocracy, Inc. “Sure, there are many venal people and ruthless capitalists here,” she says, “but right now, Joe Biden is not president in order to build up a kleptocratic fortune, keep his money in tax havens, and to make sure that all of his children become oligarchs in their own right.”

However, the upcoming elections might change that. “If Trump wins a second [term], he could alter the purpose of the American government,” she says, by, for example, turning the IRS on his enemies or using the Department of Justice to enrich himself. “I was just at a dinner last night where we asked if we could imagine Russian-style oligarchs in America, meaning people whose wealth depends on the decision of the president. And the answer is yes, you can now imagine it. It doesn’t quite exist yet, but it’s not unthinkable anymore.”

Applebaum’s answer to the threat posed by Autocracy, Inc. is for democratic nations across the world to form a coalition of their own, do so out of the shared realization that “nobody’s democracy is safe,” and work together to root out autocratic influences in their economy and politics at home and abroad.

Many nations are doing the opposite. Between Trump threatening to leave NATO and many European right-wing parties campaigning for their constituencies to follow the UK’s example and withdraw from the EU, a large portion of the Western world seemingly wants to become less involved on the global stage, not more. They want this even though isolationist policies have not only failed — Applebaum asks: “Did the removal of Britain from the European Union give the British more power to shape the world? Did it prevent foreign money from shaping UK politics?” — but also because isolationism is an unrealizable ideal.

“The most important thing looking forward is to understand the importance of working in coalitions,” Applebaum says. “There is very little that the United States can achieve by itself. Making coalitions with countries is how we’re going to make the changes that need to be made, whether it’s fighting kleptocracy and money laundering or regulating the internet, giving people control over their data, and making algorithms more transparent. All those things can be done only in concert with other countries. If you want an America that’s safe and prosperous then you do need some friends in the world. As we learned on 9/11 and through the various financial crises that followed, the world has a way of coming to you even if you don’t come to it.”