Study: unintended consequences of affirmative action

Photo by Darya Tryfanava on Unsplash

- A new study finds an affirmative action program in Brazil harms some of the people it is supposed to help.

- The assumptions and mechanisms that previously worked are now in the way.

- The key findings can be applied to many market design problems.

Public policy is difficult. Policymakers must identify problems, prioritize them, and then figure out how to address them without making other problems worse. Even then, the dreaded curse of unintended consequences remains.

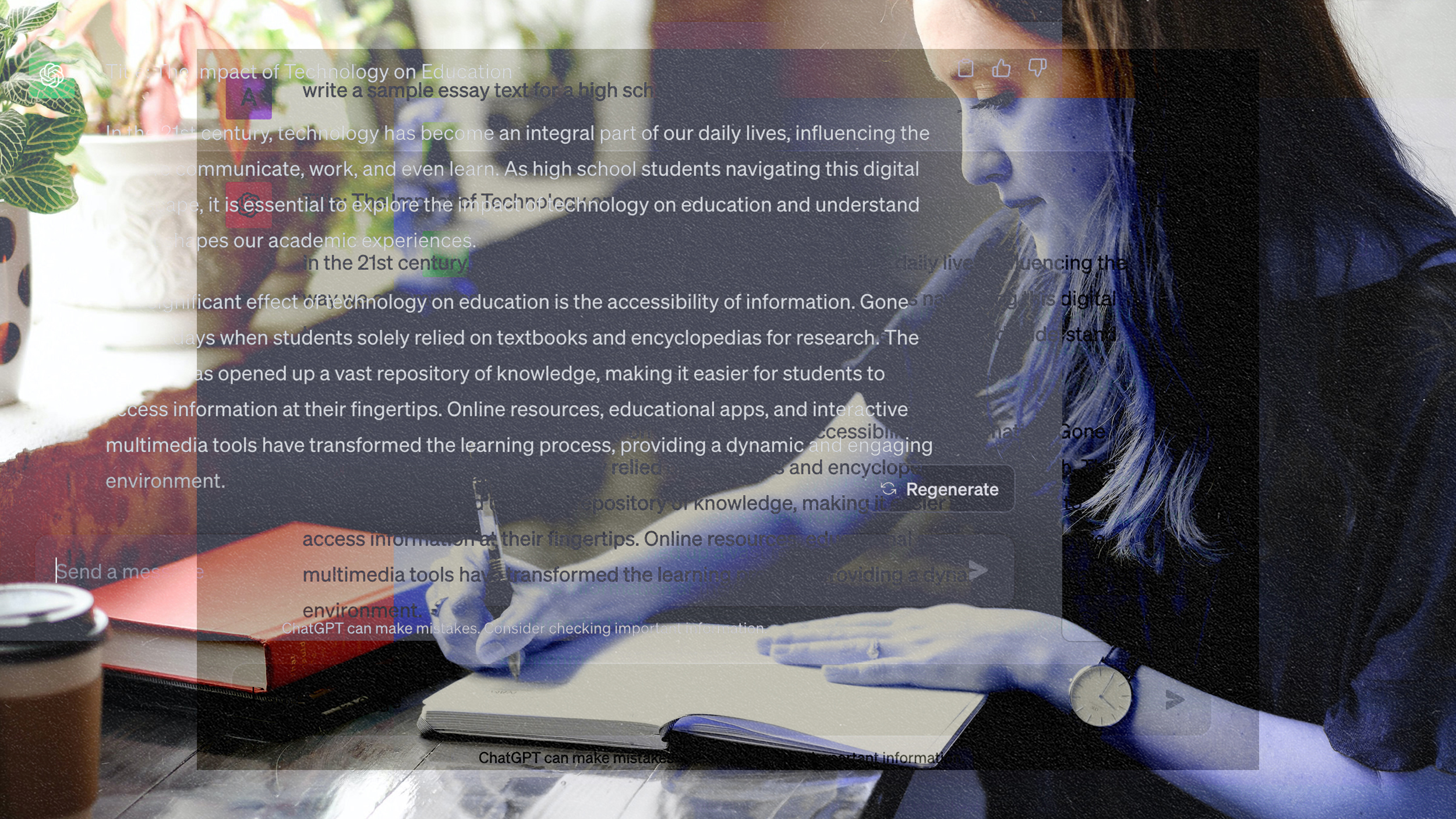

A new paper published inAmerican Economic Journal: Microeconomics provides an excellent case study by investigating the effects of an affirmative action program at Brazilian universities. While the authors accept that the policy’s objectives are praiseworthy, they show how a few missteps can make a program with good intentions work against some of the people it aims to help.

How everything works on paper

Brazilian universities have had demographic problems for some time. Namely, the makeup of the student bodies does not reflect Brazilian society as a whole. Specifically, students of Amerindian or African ancestry or low income were particularly underrepresented.

Efforts to correct this culminated in a 2012 federal law that required certain schools to set aside seats, often 50 percent of all those available, for these students. Admission would be granted to students based on merit within the targeted demographic. Though the law did what it proposed to do, those devilish unintended consequences popped up.

Perverse incentives

It turns out that the exact method by which a student applies to the program can result in perverse outcomes.The seats are grouped into sets, and each set has different criteria. For instance, one set is for students who have multiple qualifying criteria (e.g., Amerindian, African, and low-income), while another set is for students with fewer qualifying criteria (e.g., only low-income). The remaining seats were left as they were previously.

However, because it is not required for a student to claim all qualifying criteria, the student may omit criteria in order to apply for those seats that have less competition. In this way, students with low grades can gain admission by aiming for the seats nobody else is applying for.

The researchers point out examples of applicants with low grades getting seats while more qualified students were edged out in nearly 50 percent of programs implementing affirmative action. These included cases where the lowest grade needed to gain an undesignated seat was lower than that needed to get a demographically designated one.

The end result is that some students who were intended to benefit from an affirmative action policy were excluded because of how the application process worked. The authors suggest that the problem could be fixed by allowing students with multiple qualifying traits to apply for multiple seats.

You know what they say about making assumptions

The authors explain that while this case study may be limited to Brazil, most of their findings can be generalized to other market design problems.

The initial problem that prompted the affirmative action policy was inequality in university admissions that resulted from admitting students based on test scores alone. The affirmative action solution solved that problem but created another when students who were meant to benefit from the program were also high performers. Many of them were excluded due to a perverse incentive structure.

CoauthorInácio Bó explained to theAmerican Economic Association that another key takeaway is that the affirmative action program was built upon the implicit assumption that students in target demographics had lower test scores. But this isn’t universally true. Some of these students were high achievers.

Perverse incentives + flawed assumption = unintended consequences. It’s almost as if it’s a law of nature.