Do people even care about data privacy in the digital age?

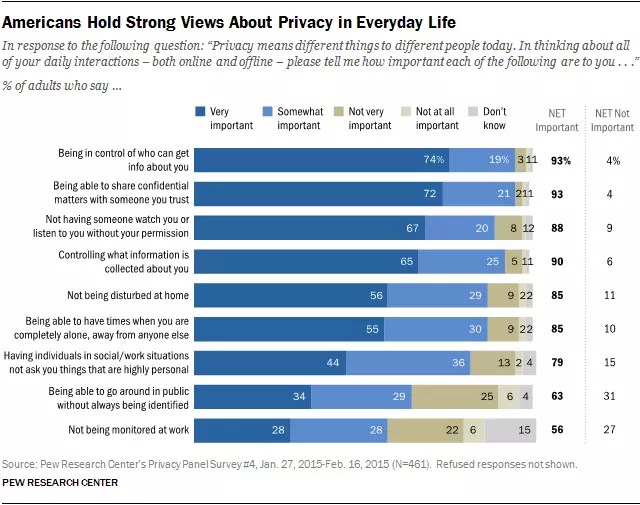

In an era where people appear to have no qualms about sharing their locations, their struggles, and their relationships online, there arises a basic question. Do people even care about privacy? The short answer is yes. A 2015 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center of around 500 adults, just two years after the Edward Snowden National Security Agency (NSA) leak, showed that Americans had strong views about privacy, and wanted to have control over who can get information about them and what information is collected about them.

Similarly, a survey of over 1,200 US internet users showed that people are less likely to speak or write about things online, share personally created content, engage with social media, and are cautious in their internet speech or search when made aware of online governmental surveillance – with women and younger adults more likely to be chilled. Furthermore, an analysis of Wikipedia data over a 32-month period surrounding the Snowden leak (after June 2013) also showed a significant drop in the number of visits to “terrorist” related Wikipedia pages, demonstrating a long-term chilling effect.

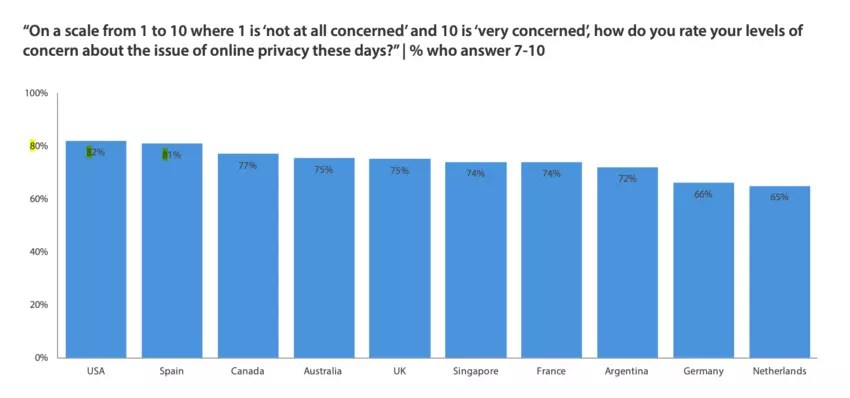

A global perspective on privacy

Privacy is not important just to Americans. There is evidence that there is a global mindset towards online privacy.

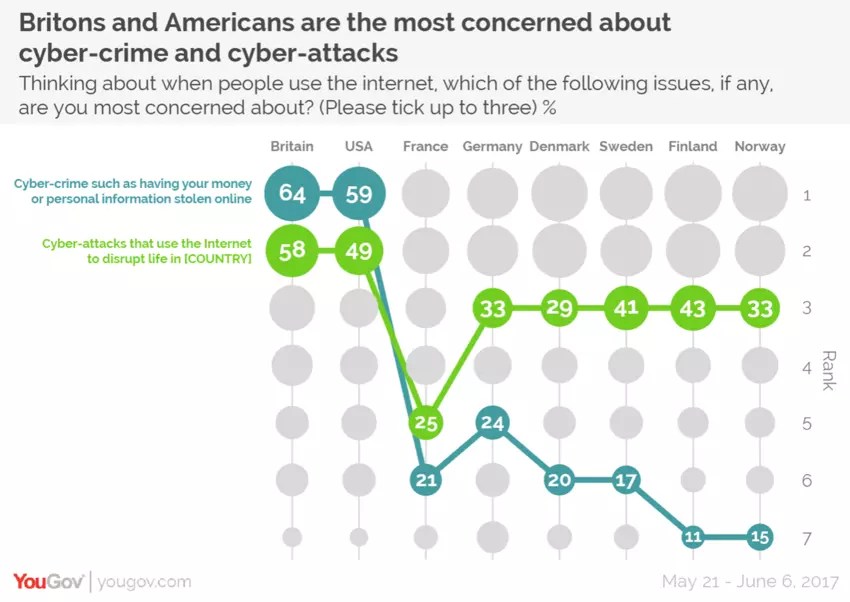

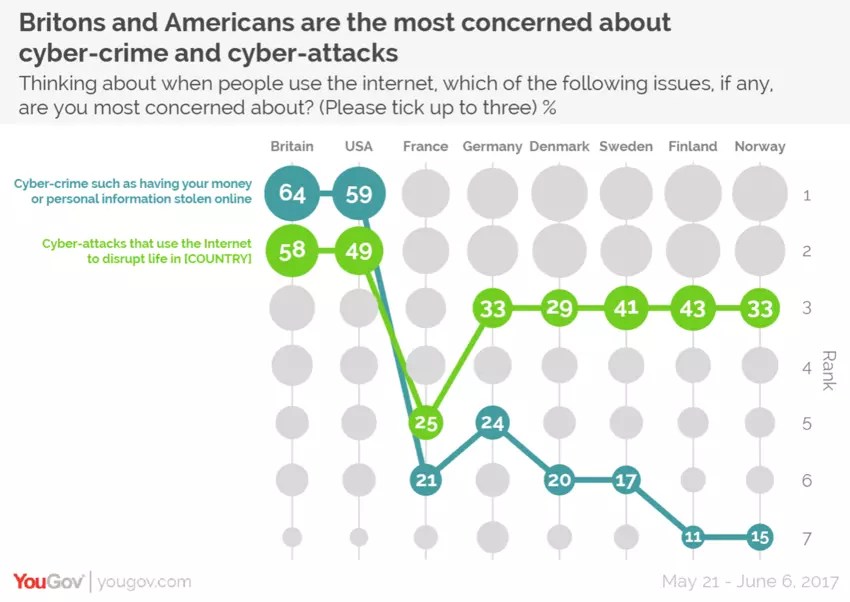

However, there are divergent privacy concerns between countries. While those in the UK and US are most concerned about cybercrimes and cyberattacks, those in Germany, France, and the Nordic countries are concerned about organizations sharing their personal information and about their children accessing inappropriate online content.

Feeling lost versus feeling in control

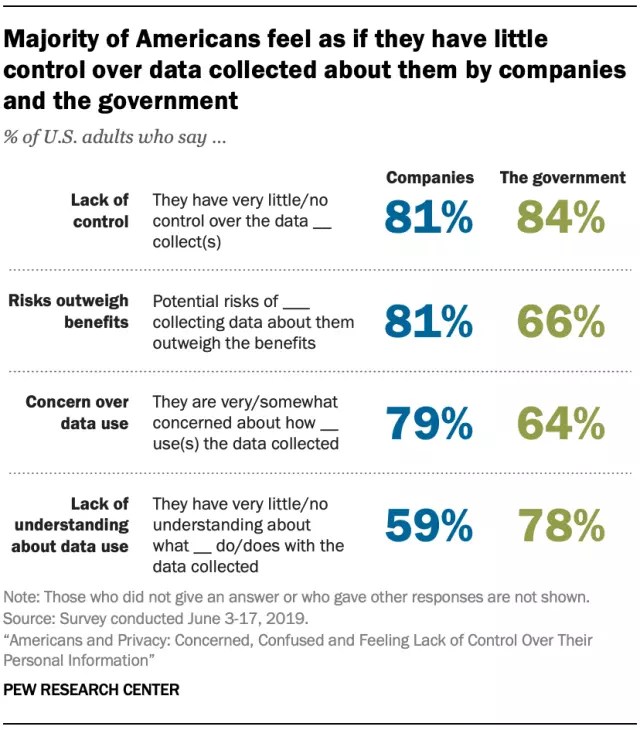

Most Americans feel they have little or no control over how government and private entities use their private information.

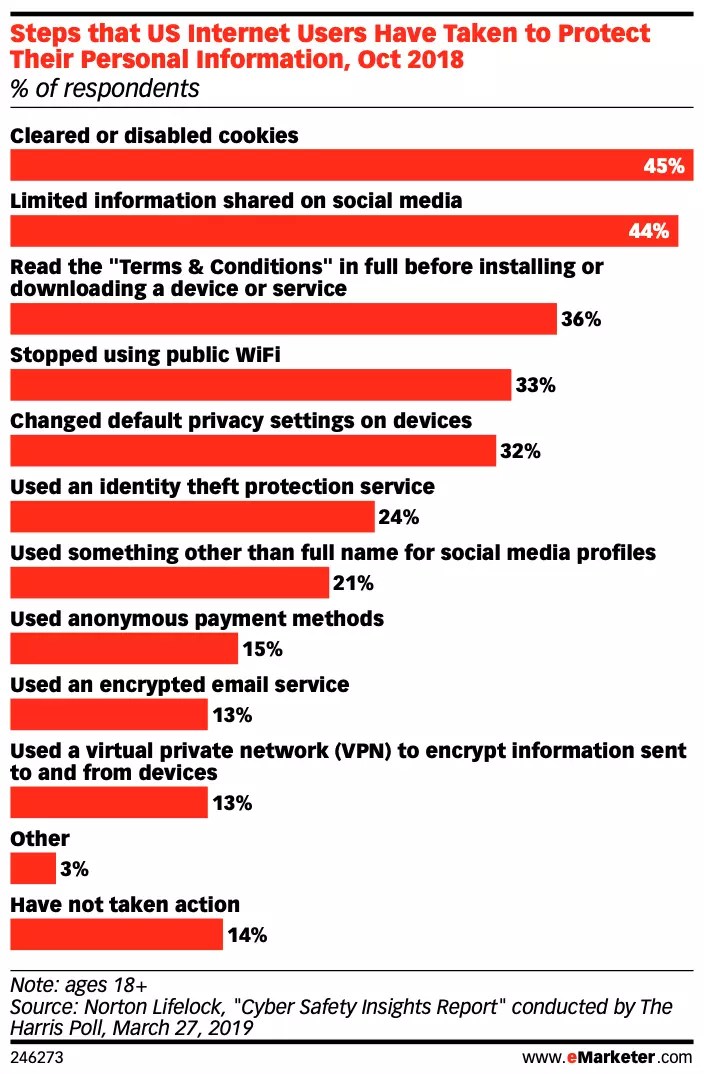

While some think that enhancing their privacy protection would be difficult, several people have taken steps to protect their personal information that includes limiting information shared on social media, clearing cookies, changing default privacy settings on devices, and using a different name other than their full name on social media profiles.

Disclosure and consent

When faced with a choice of whether to consent, people often undertake an internal “value exchange” debate, and ask themselves, “What are the benefits if I agree?” and “What are the risks?” Users also consider a variety of other factors such as their past experiences, reputation of the company behind the technology, existing social norms, whether the technology is a game changer, and how providing their personal data would impact their status.

While privacy policies are designed to inform users about their personal data being processed, these are often difficult to locate and to understand. Too frequently, users are also subject to dark patterns that manipulate them to agree or leave them with no choice but to consent in order to be able to use the feature at hand.

More recently, organizations are being required to demonstrate that users have consented to the collection and use of their personal information, and that this disclosure is presented in an intelligible and accessible manner, and users have the right to withdraw consent at any time.

Meaningful consent

Due to converging cultural and governmental forces at play, rigorous ways of designing a meaningful consent experience are more important now more than ever. A meaningful consent experience should strive to facilitate user understanding while preventing information overload, and should draw from existing human-centered frameworks (e.g., informed consent online) and include key elements such as disclosure, comprehension, voluntariness, competence, and agreement.

Republished with permission of the World Economic Forum. Read the original article.