The loss of deep reading: How digital texts impact kids’ comprehension skills

- Digital reading might be adversely affecting kids’ reading comprehension skills, a recently published meta-analysis finds. Digital reading does improve comprehension skills, but the beneficial effect is between six and seven times smaller than that of print reading.

- Digital texts, such as social media chats and blogs, tend to be much shorter and have worse linguistic quality compared to printed works. Phones and computers also expose readers to distractions from social media, YouTube, and video games.

- The authors recommend that parents and teachers limit kids’ time with digital content, or at least emphasize printed works or using basic e-readers with ink screens.

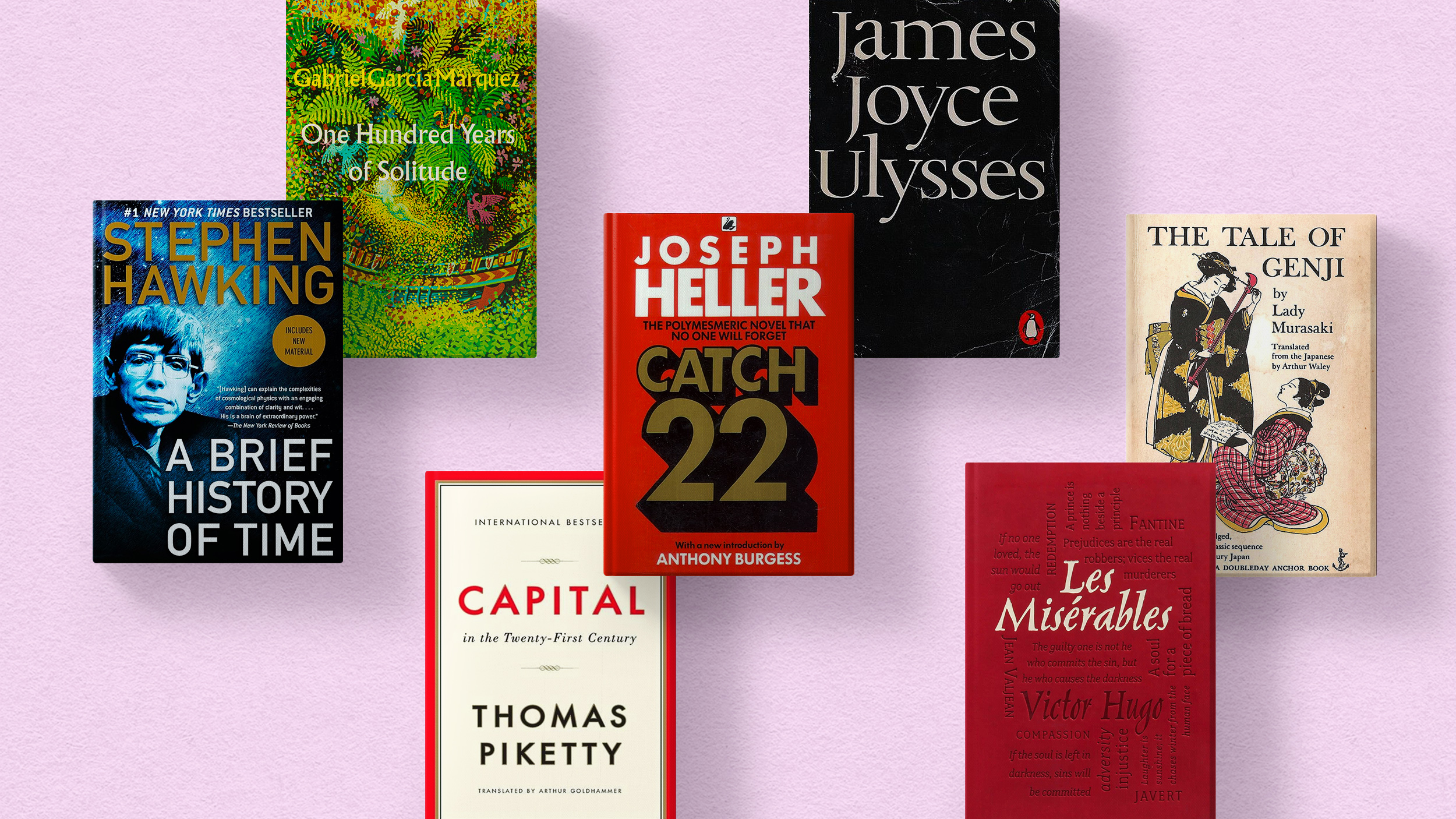

Will there ever be another Harry Potter? Between 1997 and 2007, it seemed like every child (and even their parents) was reading J.K. Rowling’s timeless fantasy novels about a skinny, bespectacled teenager’s adventures at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. Kids worldwide attended midnight parties for the launch of new installments, dressed as witches and wizards for Halloween, and spent long hours reading the thick hardcovers two, three, four, or more times.

But since the dawn of the 21st century, when digital reading of website articles, blogs, emails, social media posts, and chats began supplanting print reading, the rate of children who read for fun has plummeted. We may never again see another book series capture kids’ attention as Harry Potter did.

In addition to lessening books’ influence in the youth cultural zeitgeist, the broader switch to digital reading may be having a more pernicious effect: adversely affecting kids’ reading comprehension skills, a recently published meta-analysis finds.

Digital reading and comprehension

In 2011, scientists reviewed 99 studies exploring the effect of print reading on children’s comprehension skills. As one would expect, they found a sizable one. The more that kids were exposed to print reading, the better able they were to understand and recall what they were reading. Moreover, print reading appeared to promote a virtuous cycle: As young readers consumed longer and more complex texts, their reading skills improved, prompting them to pursue even more complex written works, further boosting their abilities.

For the new meta-analysis, scientists at the University of Valencia in Spain aggregated 26 studies with close to 470,000 participants. Each study explored the effect of leisure-time digital reading on comprehension. They found that digital reading improves comprehension skills, but the beneficial effect is between six and seven times smaller than print reading, and it’s smallest for children.

“Great [exposure] to digital reading activities… may detract early readers from building a strong reading foundational base… in a critical period when they are shifting from learning to read to reading to learn,” the authors wrote.

Why does digital reading appear to be far less beneficial? The authors cited numerous speculations from the literature. First, the linguistic quality of digital text tends to be of much lower quality. When chatting, we often use informal language with simplified vocabulary, and we ignore grammar rules. Content is also typically far shorter, not requiring the focus and retention to understand and fully enjoy longer works with intricate narratives and numerous characters.

According to Naomi S. Baron, an emerita professor of world languages and cultures at American University, a book’s physical properties might also uniquely boost information retention.

“With paper, there is a literal laying on of hands, along with the visual geography of distinct pages. People often link their memory of what they’ve read to how far into the book it was or where it was on the page,” she wrote.

The physical properties of a book or magazine — the smell, the looks, the feel — can also make reading more pleasurable, she added in an email interview with Big Think.

“If readers find pleasure in a reading medium, it wouldn’t surprise me that such pleasure would lead to greater comprehension. For sure, as many study participants informed us, print led to becoming more absorbed in stories.”

Lastly, when reading content on digital sources, distractions from social media, YouTube, and video games are often just a click away, hampering full comprehension of texts. In a recent study of undergraduates at West Virginia University, two-thirds admitted checking social media “often” or “very often” while reading. Just over half of respondents said that social media negatively impacted their reading habits, while 45% said it had a neutral effect and 2.5% said it had a positive effect.

Because youth tend to have impaired impulse control, they can be more susceptible than adults to distractions when engaging in digital reading. They also are less likely to have mastered vocabulary and grammar rules, meaning they will be exposed to more rudimentary writing on social media and in chats with friends. It’s for these reasons that the authors recommend that parents and teachers limit kids’ time with digital content, or at least emphasize printed works or using basic e-readers with ink-screens. (A 2019 study for the most part showed no difference in reading comprehension when reading works in print form versus on a Kindle, though readers were not as efficient at locating events in the temporality of the story.)

Reading into the future

Will teens follow their elders’ advice? Baron cited data suggesting they might.

“Recent data from the American Library Association point up some surprising choices by today’s Generation Z (ages 13-25) compared with those of Millennials (ages 26-40). According to their study, Gen Zers are not only reading more books per month (presumably for pleasure) than are Millennials, but are reading more print than their older brethren.”

She also noted some of her own research showing that most students readily acknowledge that they learn and concentrate better when reading print.

Could subsequent generations come back to print? Time will tell.