Does fact-checking really work? Timing matters.

Credit: TheVisualsYouNeed / Adobe Stock

- MIT researchers conducted a study with 2,683 volunteers on the efficacy of fact-checking.

- Showing “true” or “false” tags after the headline proved more effective than showing it before or during.

- The researchers believe this counterintuitive discovery could lead to better fact-checking protocols in the future.

Not only do most people get their news from social media, a majority of users never make it past the headline. The infinite scroll means that once a headline is consumed and a judgment is rendered, chances of returning to the story are low. The memory of the news is quickly filed. Once solidified, changing your mind is nearly impossible.

We all know the dangers of news-by-tweet. On Facebook you might see a headline and lede, arming you with one additional sentence of information. Still, it’s not enough, especially given the complexity of politics. Add misinformation and disinformation into the mix and the results are intellectually and socially toxic.

Yet that’s the environment we live in. Share an article from a fact-checking website like Snopes and you’re guaranteed to hear about a past incident involving the founders or the notion that Politifact is biased. The Washington Post tracked over 30,500 lies or misleading claims by Donald Trump in four years; his followers never blinked.

Rarely are debates argued on the merits of content. Emotionality rules on social media. If the site is not agreeing with the narrative you’ve already told yourself, it must be wrong.

Does that make the very concept of fact-checking impossible? A new study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, argues against that idea—with caveats, of course. As MIT professor and co-author David Rand says, “We found that whether a false claim was corrected before people read it, while they read it, or after they read it influenced the effectiveness of the correction.”

Neil deGrasse Tyson: How science literacy can save us from the internet | Big Thinkwww.youtube.com

For the study, 2,683 people viewed 18 true and 18 debunked news headlines. Three groups saw the words “true” or “false” written before, during, or after the headlines, while a control group saw no tags. They then rated the accuracy of each headline. A week later everyone returned and again rated headline accuracy, only this time no one received “true” or “false” prompts.

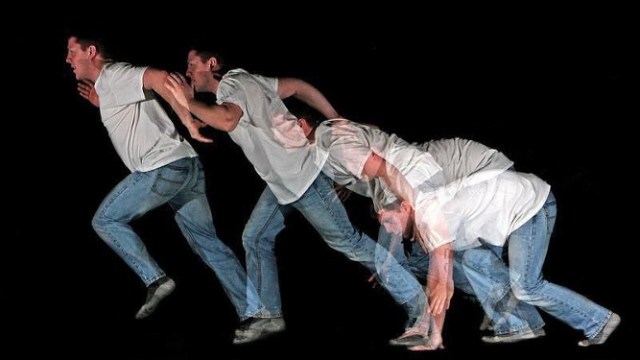

As with everything in life, the researchers discovered that timing matters. And it really matters, given that 44 percent of Americans visited “untrustworthy websites” leading up to the 2016 presidential election—certainly enough of an impact to sway an electorate.

When volunteers were shown the label immediately before the headline, inaccuracies were reduced by 5.7 percent; while reading the headline, 8.6 percent; and after the headline, 25.3 percent. Rand notes his shock at discovering this sequence.

“Going into the project, I had anticipated it would work best to give the correction beforehand, so that people already knew to disbelieve the false claim when they came into contact with it. To my surprise, we actually found the opposite. Debunking the claim after they were exposed to it was the most effective.”

AFP journalist views a video on January 25, 2019, manipulated with artificial intelligence to potentially deceive viewers, or “deepfake” at his newsdesk in Washington, DC. Credit: Alexandra Robinson/AFP via Getty Images

While there’s no silver bullet for battling misinformation, the researchers speculate that allowing people to form an opinion and then providing feedback might help the information “stick.” Prebunking headlines might seem like the best strategy, though it actually has an opposite effect: readers gloss over the headline knowing it to be false. When later asked to judge, they didn’t properly categorize the news as they weren’t actually paying attention.

By contrast, showing the tags directly after reading the headline seems to “boost long-term retention” of truthfulness. One interesting phenomenon: the sense of surprise after a low-confidence guess turns out true reinforces the stickiness of the information. Learning the truth after an initial judgment seems to be the best course of action.

How this could be implemented in the age of infinite scrolling remains to be seen. But it does run counter to current practices by Facebook and Twitter, which mark false stories with a warning before you’re allowed to view them. While this seems to be the right way to go, recall human nature: we love forbidden fruit. Tell us “this is wrong” and watch the results.

In fact, you don’t need to—the MIT researchers did it for us. We know we need new models of news gathering and consumption. This study could provide at least one mechanism for achieving such a model.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook. His most recent book is “Hero’s Dose: The Case For Psychedelics in Ritual and Therapy.”