Stanford engineers warn that electric car charging could crash a grid powered by renewable energy

- Most EV owners currently charge their vehicles at night, but that could be a problem in the next decade when more EVs are on the road and the grid is increasingly based on wind and solar.

- EVs require a lot of energy to charge and solar energy production falls off at night. That means that utilities will have to rely on fossil-fuel peaking plants or a lot of grid storage to supply power.

- A simpler solution would be to encourage daytime charging of EVs while most drivers are at work. This would protect the grid and lower costs for all.

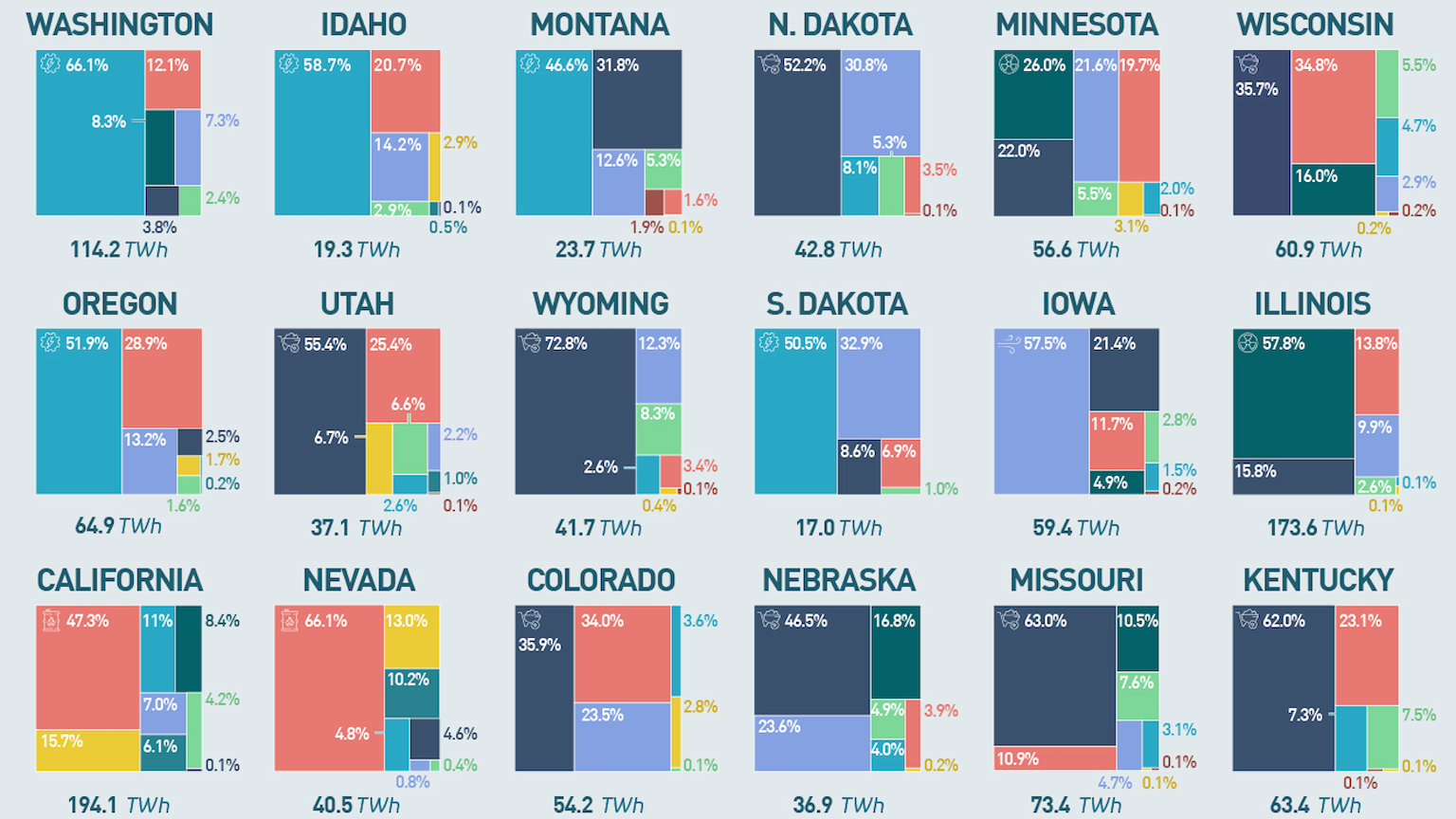

Renewable energy and electric vehicles (EVs) are key to decarbonizing the U.S. and combating climate change, but the technologies could have a hard time co-existing when it comes to charging, particularly out West, a new analysis finds.

A looming problem

Most EV owners currently charge their vehicles at night when they aren’t in use, taking advantage of cheaper, off-peak electricity rates when demand is low and fossil fuel (mostly natural gas) or nuclear power plants are providing much of the electricity. But by 2035, with hotter nighttime temperatures requiring more air conditioning, a low-carbon grid powered predominantly by wind and solar, and tens of millions of EVs on the road, charging those vehicles at night — when the sun isn’t shining — could overburden the power grid.

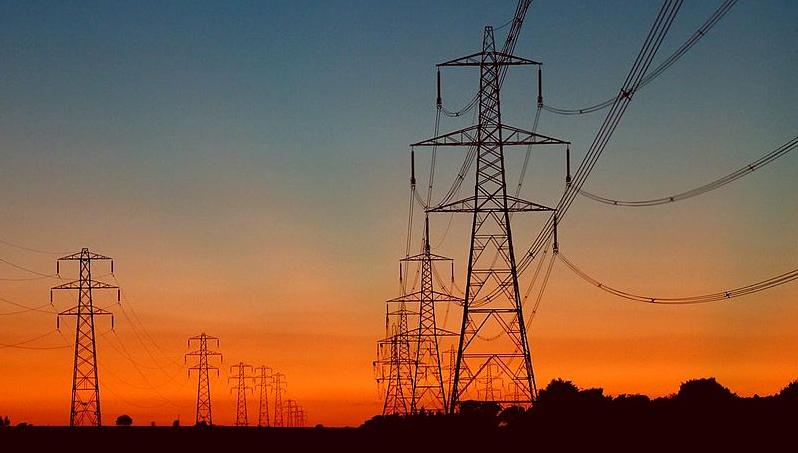

At any given time, electricity-generating sources connected to the power grid — power plants, solar panels, wind turbines, etc. — need to produce more energy than the total demand from consumers, be it from appliances, lighting, EV charging, or anything else that requires electricity. If there’s not enough generation to meet demand, slight or complete loss of power can occur.

The team of Stanford engineers behind the new report, published in the journal Nature Energy, found that mass EV adoption — where 30%-40% of vehicles or more are electric — coupled with owners charging those EVs in the evening or at night, could shift peak electricity demand on the Western Interconnection, the power grid covering the western U.S. and western Canada, from late afternoon to around 8-9 p.m. and raise it by up to 25%. Meeting this higher demand could necessitate quickly firing up fossil fuel-based “peaker” plants or relying on 10 to 24 gigawatts of grid storage, mostly from batteries charged during the day from excess solar generation. The former option is incredibly polluting, while the latter requires a massive build-out, about 40 to 100 times the grid storage that was available in 2019. Both methods are extremely expensive.

A possible solution

A better solution, the Stanford engineers say, is to encourage EV charging at work during daylight hours when solar energy production is at its zenith.

“We encourage policymakers to consider utility rates that encourage day charging and incentivize investment in charging infrastructure to shift drivers from home to work for charging,” the study’s co-senior author, Ram Rajagopal, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford, said in a statement.

Electric car sales are soaring, and there is a three-month or even two-year wait for most models. EV sales are projected to rise from 5% of all new vehicle sales in 2022 to 30% in 2030. Thus, owners out West might need to adopt the Stanford engineers’ recommendation sooner rather than later.

Electric cars in the future

In a future world where 90% of all vehicles in the U.S. are EVs, charging alone could account for one-third of all electricity use. It’s imperative that this unprecedented rise in demand be spread out during the day to prevent usage peaks that are mismatched with renewable energy production. Innovative software and technology that allows fully-charged electric cars to provide energy back to the grid could also help.

“By avoiding the evening peak and better aligning with renewables, daytime-charging scenarios reduce the amount of storage required to support EV charging and free it to provide other services,” the authors write.