Timothy Snyder on what Americans get wrong about freedom

- Timothy Snyder, an American historian, explores the evolving concept of freedom in his 2024 book On Freedom, distinguishing between negative freedom (freedom from obstacles) and positive freedom (freedom to build and create).

- Snyder argues that true freedom goes beyond the removal of oppression and requires the active construction of a better society.

- Lasting freedom may require a balance between individual autonomy and the social conditions that support personal growth and security.

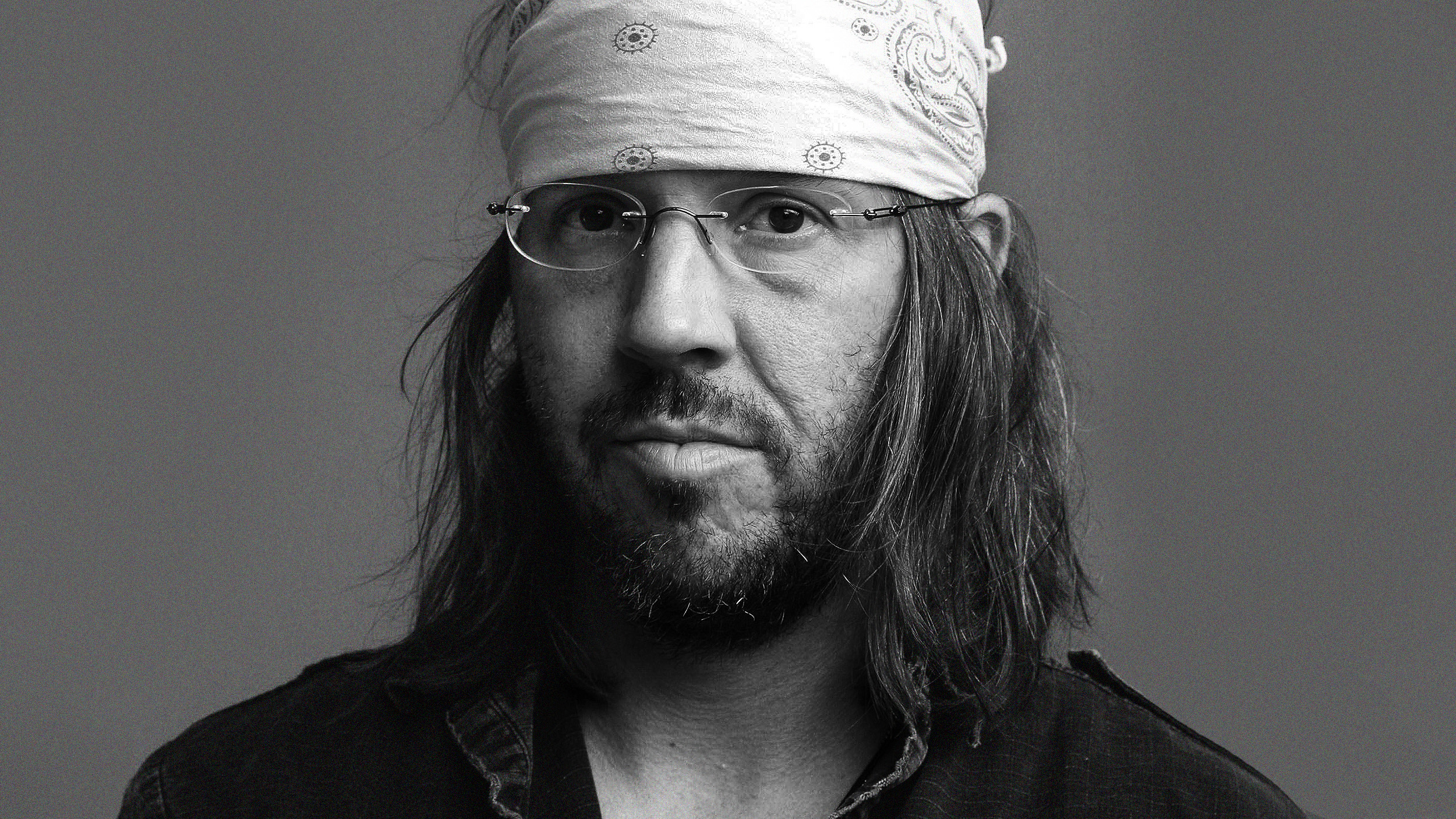

During a trip to war-torn Ukraine in September 2023, Ohio-born historian and author Timothy Snyder couldn’t help but notice Ukrainians describing their collective dream — an end to the war with Russia — as “de-occupation” as opposed to “liberation.”

This term, he reflects in his new book On Freedom, “invites us to consider what, beyond the removal of oppression, we might need for liberty.” To the Ukrainians, freedom does not simply mean the absence of Russian soldiers, but also the reconstruction of society — of schools, hospitals, and roads — and making sure everything functions even better than it did before the war began.

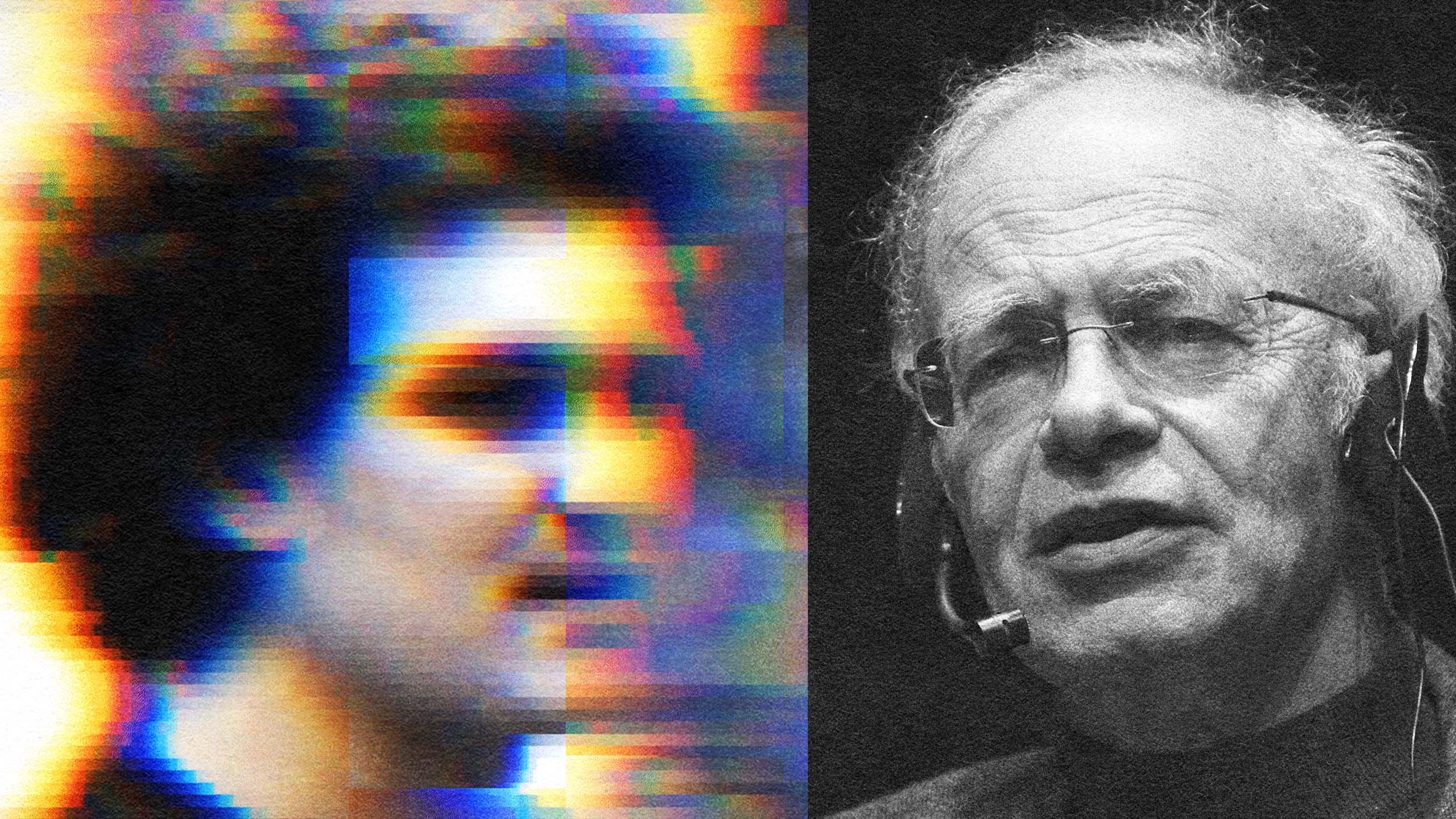

The Ukrainian definition of freedom is very different from how it’s commonly defined in the United States, where overuse has divested the term from its true meaning. When contemporary Americans talk about freedom, they’re usually referring to what the Russian-British philosopher Isaiah Berlin called negative freedom: freedom from something, like a dictator invading your land, or the government taking away your right to bear arms. By contrast, Ukrainians tend to talk about positive freedom: the freedom to do something, like building robust social institutions.

In his 2024 book On Freedom, Snyder shows readers how to distinguish negative from positive freedom, and explains why the latter is preferable to the former. “When we assume that freedom is negative, the absence of this or that,” he writes in the introduction, “we presume that removing a barrier is all that we have to do to be free. To this way of thinking, freedom is the default condition of the universe, brought to us by some larger force when we clear the way. This is naïve.”

Definitions of freedom

Isaiah Berlin was hardly the first philosopher to try to define freedom. Socrates, as told through Plato’s dialogues, believed it could only be achieved through reason. Arthur Schopenhauer, inspired by Buddhism, argued freedom resulted from letting go of one’s desires; Friedrich Nietzsche, from enduring suffering and hardship. The list goes on.

“For a long time,” Snyder tells Big Think, “the dominant American understanding of freedom has been one of negative freedom, such as freedom from big government. In this understanding, someone else is the problem, standing in the way of us being free.”

Interestingly, this understanding of freedom comes not from the American Constitution itself as it does the culture and customs of the period in which that document was created, such as slavery in the South and the fight for land ownership on the frontier. “If I own slaves, or my fortune rests on the labor of others,” Snyder says, “I’m naturally going to define freedom as freedom from the government because that’s the only force that could liberate my slaves or workers.”

Today, this argument remains extremely appealing to well-to-do Americans in favor of small government. “If I’m a Silicon Valley oligarch with crazy ideas about the way the country should be run and $100 billion in the bank,” says Snyder, “I too would want the government to be small, as it’s the only force that could regulate my business or require me to treat other people with more dignity.”

One of the problems with this understanding of freedom is that one person’s negative freedom (i.e. the freedom to own guns) almost always comes at the expense of another person’s positive freedom (i.e., the freedom to go to school or the mall without the threat of being shot). What’s more, negative freedom prevents people from thinking about freedom positively and more constructively. As Snyder puts it: “If the government is the problem, I never have to ask what being free means. What do I want to be? What do I care about? Those are questions that a traditional, negative conception of freedom does not allow us to answer.”

In the US, defenders of the Second Amendment often resort to Originalism, the theory that legal documents — including the US Constitution — should be interpreted in the way the authors of those documents would have interpreted them. In other words, if the Founding Fathers wanted people to own guns in their time, the descendants of those people should be granted the same right in ours. Snyder prefers to interpret the Constitution through a historical lens:

“Often the way that the discussion of liberty works in the US is that we say, ‘Oh well, you know, Madison said this and Hamilton said that, and Jefferson and Washington said something else.’ I think the right way to think about the Founders is that they were rebels in their time. And if you want to emulate them, you have to be a rebel in your own time. You have to push freedom forward, which doesn’t mean falling back to definitions from the 18th century. I want us to see the Founders in their time, a time when it was normal for the exploitation of some to be defined as the freedom of others.”

Security and unpredictability

How should we think about freedom instead if not in the contemporary American way?

One person who influenced Snyder’s positive conception of freedom is Edith Stein, a German Jewish philosopher who died at Auschwitz. “Americans think: I’m free because I’m right and you’re wrong, and you’re standing in my way. Stein’s work reminds us we actually don’t know ourselves very well, and the only way we can know ourselves is to listen to each other, and we only really listen to somebody else if we take them seriously as human beings.”

French philosopher and political activist Simone Weil, who also died during the Second World War, is another source of inspiration because she “argued that many things which appear to be restraints can also be seen as tools.” If you live in a negative freedom world, you’re living in a world of restraints. But many of those restraints can also be seen as fulfilling basic human needs. “Gravity is a restraint that allows us to walk,” Snyder says. “Walls keep us apart, but you can also use them to hold up a roof and build a shelter. If we only think of restraints as barriers, sometimes we’re not able to create the tools that we need to become more free than we are.”

More inspiring still is Václav Havel, a poet, playwright, and political dissident who served as president of Czechoslovakia from 1989 to 1992. While the communist regime of his upbringing championed socioeconomic equality, Havel felt its dictatorial policies and secret police robbed people of their agency and individualism. Living in a society whose citizens were too afraid to speak their minds, he concluded that humans can only be free if they are allowed to be unpredictable — to make their own choices and behave authentically — even when it went against the preferences of their politicians.

The Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky made a similar argument in his 1864 novella Notes from Underground, which, published amidst a sea of Marxist novels and treatises, argued that the creation of a socialist utopia would by definition turn its inhabitants into robots, ever acting in predictable and decidedly unhuman harmony:

“Good heavens, gentlemen, what sort of free will is left when we come to tabulation and arithmetic, when it will all be a case of twice two makes four?”

The ideas presented by Dostoevsky and (to a lesser extent) Havel have long appealed to conservatives campaigning against left-leaning policies in the United States. But the US is not the USSR, and while Snyder agrees it’s impossible to be unpredictably free when living under the auspices of a full-blown dictatorship, he nonetheless suggests that the freedom to live authentically and unpredictably can only arise from the material security provided by the modern welfare state.

“If you decide to quit your job in a welfare state setting,” he says, “you have much more room to that than you would in a country like the United States. Americans can’t easily leave jobs they don’t like because they’re connected to their health insurance. When I moved to France at the age of 24 or 25, I thought the whole European setup was kind of hilarious. Why do people take such long vacations? What is it for? I didn’t understand because I was an American, and I thought you just work all the time — that’s life.”

Western Europe’s extensive welfare programs and public services left a favorable impression on Snyder, so much so that, when he later returned to his home country, he began to notice unfreedoms he did not perceive before. “I don’t think you’re so free if you have to own a car,” he says. “I like cars. I like to drive. I’m from the Midwest. I grew up driving. But if you can’t get from one city to the other without owning a car, you’re less free than somebody who can hop on a train and get from one city to another.”

If the US embodies freedom in any sense of the word, it’s the energy and enthusiasm with which many Americans strive to fulfill their lofty American Dreams. Snyder does not discredit these qualities. “I’m trying to define freedom in such a way that it justifies both the dream and the security because I think it’s actually about both. You need the dreamers, but when they fall off the trapeze, you don’t want to hit the cement. You want there to be a net.”