Gender equality in STEM is possible. These countries prove it.

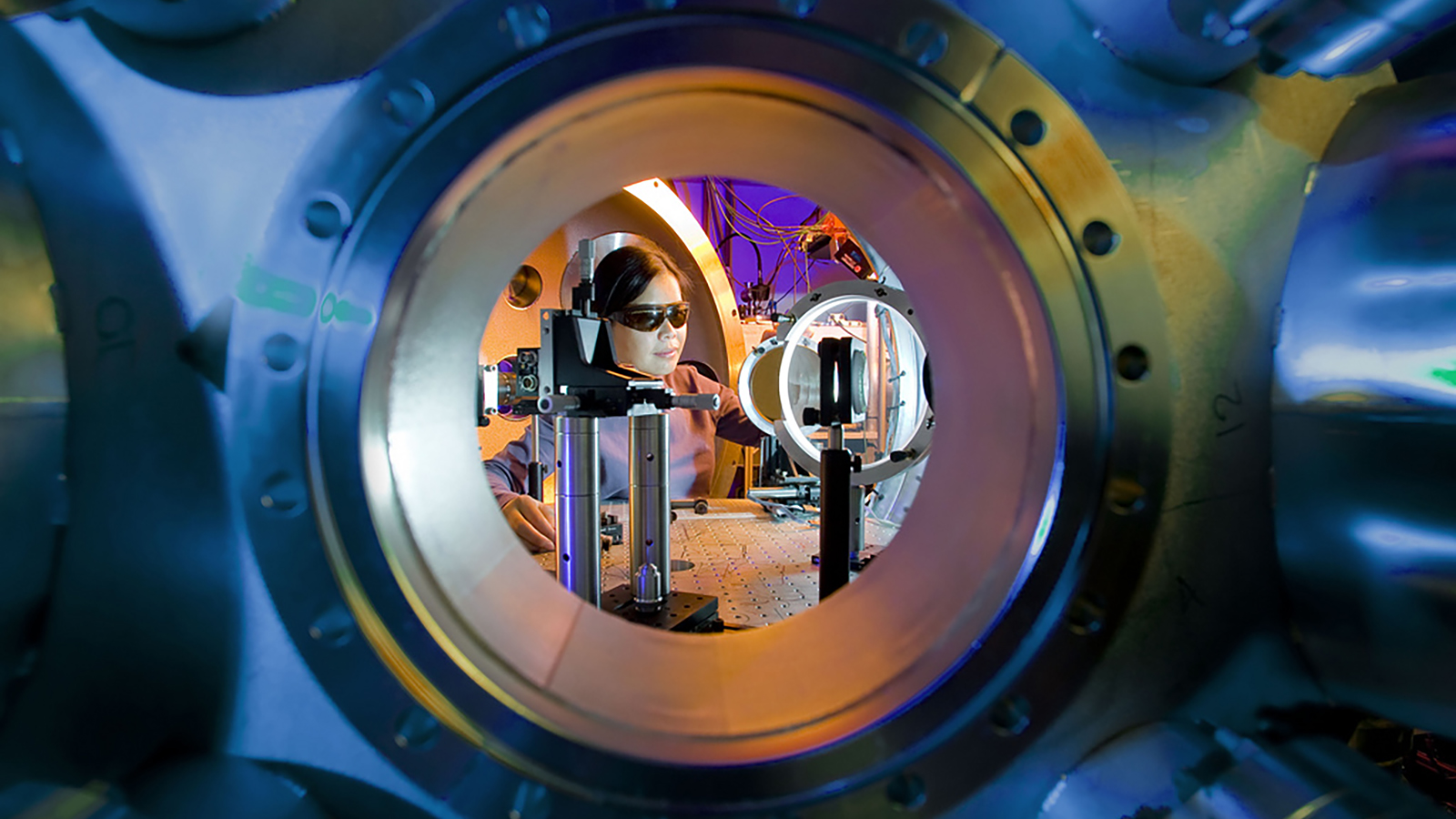

Forensic scientist Jasmine Thomas prepares blood samples for DNA extraction for evidence in a sexual assault case in the Forensic Evidence section of the Louisiana State Crime Lab June 4, 2003 in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. (Photo by Mario Villafuerte/Getty Images)

There should be no shortage of inspirational role models for young girls dreaming of a career in science. Women have been responsible for some of the most important scientific breakthroughs that shaped the modern world, from Marie Curie’s discoveries about radiation, to Grace Hopper’s groundbreaking work on computer programming, and Barbara McClintock’s pioneering approach to genetics.

But too often their stories aren’t just about the difficulties they faced in cracking some of the toughest problems in science, but also about overcoming social and professional obstacles just because of their gender. And many of those obstacles still face women working and studying in science today.

Globally 72 percent of scientific researchers are men. Only one in five countries achieve what is classed as “gender parity” with women making up 45–55 percent of researchers. And in only a handful do women working in science outnumber men — with distinct regional variations.

In the EU 41 percent of scientists and engineers are women. But women outnumber men in those professions in Lithuania, Bulgaria, Latvia, Portugal and Denmark, as well as in non-EU member Norway.

But less than a third of researchers are women in Hungary, Luxembourg, Finland and, perhaps most surprisingly, Germany, which is actually led by an accomplished female scientist, Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Across Europe as a whole, men dominated high and medium high-technology manufacturing: 83 percent of scientists and engineers are male in those sectors, compared with 55 percent in scientific services.

In Asia, women make up the majority of researchers in Azerbaijan, Thailand, Kazakhstan, Georgia, Armenia and Kuwait.

In the Americas, Bolivia, Venezuela, Trinidad & Tobago, Guatemala, Argentina, and Panama all have more than 50 percent female researchers, as do New Zealand and Tunisia.

So what is special about these countries?

For some, especially in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, the gender parity in science is a legacy of their membership of the Soviet Union and its satellite bloc, where female participation in science was actively encouraged, often in government-funded facilities. Others, like the Nordic countries, lead the world in gender equality thanks to ambitious welfare and social policies that help women in the workplace.

Globally, women tend to be employed more in the public sector, while even in countries with gender parity, such as Latvia and Argentina, men are over-represented in the private sector, where wages are often higher.

Women are also better represented in the health sector, as opposed to engineering and information technology, so that countries with more prominent medical research tend to have a better balance of women.

All over the world, there is the phenomenon of the “leaky pipeline” of lost talent. Girls are attracted to science at school, and actually make up the majority of science graduates with bachelor’s degrees. Even at master’s level women are in the majority.

But there is a dramatic drop in numbers at Ph.D. level, and the discrepancy gets wider still at researcher level.

Even when women are employed, they often face significant glass ceilings. In the U.K., for example, the proportion of women at management level in science and technology is just 13 percent. The effect is found in academia as well. One study found that while 61 percent of bioscience postgraduate students were women, just 15 percent of their professors were. There is also evidence that women are typically given less money in research grants, and find it harder to obtain venture capital for science and technology start-ups.

Some women put off careers in science because of the difficulty of combining work with family life — although, as in many other professions, those issues can be addressed with changes in policy and workplace behaviour. But deeper cultural stereotypes play a significant role too. UNESCO has pointed to a “persistent bias that women cannot do as well as men” that is self perpetuating, and often informs women’s view of their own capabilities and achievements.

But these stereotypes can be overcome. India has seen a substantial increase in women studying and working in engineering, once seen as a “masculine” discipline. Parents often encourage daughters into engineering because of good employment prospects, and a perception it is a “friendlier” area than computer science. The role India’s female engineers — the “rocket women of ISRO” — have played in the country’s space program has been widely celebrated.

Increasing the number of women in science isn’t only about harnessing the best talent to tackle the challenges facing humanity. Science is often a foundation for well-paid careers that boost the economic security of women, and, in turn, give them a greater social and political voice.

And as the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report makes clear, the benefits this can bring are shared by society as a whole, whatever one’s gender.

—

Reprinted with permission of World Economic Forum. Read the original article here.