Japan moves forward with nuclear power, Germany moves backward

- A decade after the Fukushima nuclear disaster, Japan is moving ahead with plans to restart its nuclear power infrastructure.

- Germany, a nation with a long history of anti-nuclear sentiments, is on track to phase out all of its nuclear power plants by 2022.

- In a recent open letter, a coalition of scientists and journalists argued that Germany will not hit its climate goals if it phases out nuclear.

In March 2011, a tsunami struck Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, triggering three nuclear meltdowns and leaking radioactively contaminated water miles out into the Pacific Ocean. It was the worst nuclear accident since Chernobyl in 1986. Shaken by the disaster and uncertain of the safety of its remaining nuclear power plants, Japan shut down all but one of its nuclear reactors.

But it was Germany that responded most severely to the Fukushima disaster. Facing strong political and public opposition to the nation’s own nuclear infrastructure, the German government began closing nuclear power plants and set plans to phase out all of the nation’s nuclear facilities by 2022.

Japan, however, is planning to restart its nuclear power program. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida said at a press conference earlier this month that it was “crucial” for the country to bring its nuclear reactors back online, noting that the nation’s demand for electricity is projected to spike. Likewise, Japan’s industry minister recently said that he would like “to promote the maximum adoption of renewable energy, thorough energy conservation, and the restart of nuclear power plants with the highest priority on safety.” These efforts, he said, will push Japan toward its goal of carbon neutrality by 2050.

Germany has bold climate goals, too, aiming for net-zero emissions by 2045. The plan is called “Energiewende,” or energy transformation, and its ultimate goal is to curb emissions by moving away from fossil fuels and toward more sustainable energy sources. Nuclear power plants, which do not emit greenhouse gases, will not be among them.

What is driving Japan and Germany — two nations with similar sustainability goals and existing nuclear infrastructure — to take such different approaches on nuclear power? The answer is part history and part geopolitics.

Germany’s anti-nuclear movement

There is deep-seated skepticism toward nuclear power in the German public’s consciousness. One of the first major flashpoints in Germany’s anti-nuclear movement occurred in 1975 when construction began on a nuclear power plant in Wyhl, Germany. Hundreds of locals, many of whom were conservative farmers and vintners, turned out to protest the construction and occupy the site.

The demonstration ultimately attracted more than 20,000 protesters who occupied the site for months. Television news crews captured video of police violently dragging away protesters — images which helped turn nuclear power into a national issue. Construction plans were eventually scrapped, and the success of the demonstration established a model for future anti-nuclear protests.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of thousands of anti-nuclear activists showed up to protest the construction of nuclear facilities in Germany. One major battleground was the Brokdorf nuclear power plant. Clashes between police and protesters around the plant often turned violent; demonstrators threw rocks and Molotov cocktails, cars were burned, and people on both sides were seriously injured. Still, the Brokdorf plant was eventually built.

The 1986 Chernobyl disaster sparked the greatest fears over nuclear power in Germany. As the nuclear fallout cloud drifted over Europe, Germans grew fearsome of radioactive contamination, especially in West Germany. Officials ordered people not to drink milk, eat forest mushrooms, or let kids play outside. Some pregnant German women even had abortions, fearing that their children might be born with abnormalities. (As of yet, no research has conclusively shown that the Chernobyl disaster caused any adverse health effects to people in Germany.)

Meanwhile, Soviet-controlled East Germany was not nearly as rattled by what state-run media downplayed as “the incident.” A newspaper headline published shortly after the Chernobyl meltdown read: “Experts say: No danger from Chernobyl in East Germany.” Most East Germans remained unaware of the extent of the disaster until reunification in 1990.

Germany and the Fukushima disaster

Germany built its last nuclear power plant in 1989. A decade later, a coalition between Germany’s Social Democratic Party and Green Party established plans to phase out all nuclear power plants by 2022. But in 2010, when Germany was generating more than 20 percent of its electricity from nuclear power plants, Chancellor Angela Merkel extended the phaseout schedule to the mid-2030s. As other politicians had promised in the past, the extension was framed as a “bridge” to help the nation generate cost-effective power until renewables could take over.

But just a few months later, the Fukushima disaster struck. Germany’s anti-nuclear movement had already been enraged by the phaseout delay; the disaster only fueled their opposition. Germany swiftly closed most of its nuclear reactors and reestablished 2022 as the deadline for the phaseout — called the atomausstieg. Germany’s environment minister said at the time: “It’s definite. The latest end for the last three nuclear power plants is 2022. There will be no clause for revision.”

It marked a public turnabout for Merkel, a physicist who obtained a doctorate in quantum chemistry in 1986, the same year as the Chernobyl disaster.

“I will always consider it absurd to shut down technologically safe nuclear power plants that don’t emit CO2,” Merkel said in 2006.

The use of nuclear power dwindled in post-Fukushima Germany. Demand for electricity did not. To compensate for the electricity supply lost as a result of closing nuclear plants, Germany mostly resorted to burning coal. A 2019 study estimated that this resulted in a five percent increase in annual greenhouse gas emissions.

Despite leaning on coal, Germany has one of the highest renewable energy capacities in the world, generating more than 40 percent of its power from renewable sources like solar, wind, and geothermal. Still, some experts fear the nation will fail to meet its climate goals without nuclear power.

In an open letter published Oct. 14 in Welt, a coalition of 25 journalists, scientists, and academics called on German lawmakers to cancel nuclear phaseout plans:

“Your country cannot afford such an unnecessary setback at a time when its emissions are already rising sharply again after the pandemic: in 2021 they will probably be only 37 percent below the level of 1990 and thus still 3 percentage points above those for 2020 target of a 40 percent reduction (which was effectively missed). The expansion of renewable energies and the construction of north-south transmission lines are also currently being delayed, while the recent steep rise in natural gas prices is favoring the burning of coal.”

The recent German election looks to return the Social Democrats and Greens to power. It remains to be seen how the post-Merkel government will handle energy policy, but the prospect of a nuclear revival seems more dismal than ever.

Japan’s stance on nuclear power

Nuclear energy has been a far less contentious issue in Japan. As a resource-poor country that imports much of its energy, nuclear power has been an important contributor to the nation’s energy supply since the 1970s. But that’s not to say that the Japanese public has wholeheartedly supported nuclear power.

In the 1990s, a handful of accidents — and subsequent government cover-ups — eroded Japanese citizens’ trust in nuclear power. The worst was the 1999 accident at the Tōkai nuclear power plant, which killed two workers and exposed more than 600 nearby people to dangerously high levels of radiation. The disaster left 52 percent of the Japanese public feeling uneasy about nuclear power, up from 21 percent before the accident.

Still, before Fukushima, Japan’s imperfect yet sophisticated nuclear infrastructure was considered an emblem of the so-called nuclear renaissance, a term coined in the early 2000s to refer to a potential revival of nuclear power around the world. In the 2000s, Japan was generating about 30 percent of its electricity from nuclear power, with plans to boost that rate to 40 percent by 2017.

But then the tsunami struck. Amid safety concerns and dwindling public confidence and political support, Japan shut down its nuclear plants, forcing other energy sources to meet existing demand — a move that, some research estimates, significantly raised the cost of electricity across the nation.

As in Germany, the psychological fallout from the Fukushima disaster was devastating in Japan. In September 2011, more than 20,000 people gathered in Tokyo to protest nuclear power, chanting things like, “Sayonara nuclear power!” and, “No more Fukushimas!” The next summer, some 170,000 people again protested nuclear power in Tokyo. Adding to the fire were investigations published in 2011 showing that nuclear companies had conspired with government officials to manipulate public opinion in favor of nuclear power.

Although anti-nuclear sentiment was never quite as strong in Japan as it was in Germany, the Fukushima protests did seem to set a new precedent for Japanese protest movements in general; compared to other developed nations, large-scale protests had been relatively rare in Japan after the 1960s.

Today, surveys suggest that about half of Japanese citizens think that the nation should gradually phase out nuclear power. Only 11 percent seem to feel positively about the energy source. Despite concerns from the public, Japan is moving ahead with restarting its nuclear power infrastructure.

Considering the opportunity costs of shutting down nuclear power and the strategic disadvantages of relying on imported fossil fuels for electricity, the Japanese government began updating its energy plan in 2018 to include more power from nuclear plants. Prime Minister Kishida, who took office on October 4, is proposing a mixed-energy future for Japan, one focused on maximizing sustainability and self-sufficiency while minimizing costs.

The safety and sustainability of nuclear power

Is nuclear power sustainable? The answer is a definite yes, assuming that accidents are rare and radioactive waste is properly handled.

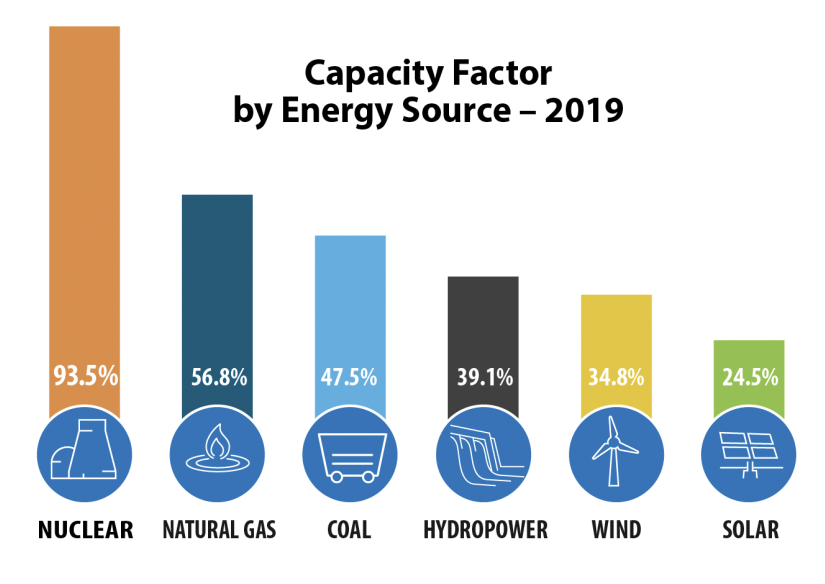

Nuclear power plants produce energy through nuclear fission — a process that does not pollute the environment with carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases. Compared to all other energy sources, nuclear power plants have, by far, the highest capacity factor, which is a measure of how often a power plant is producing energy at full capacity in a given period of time. Renewables sometimes lack in this department: the wind doesn’t always blow, and the sun doesn’t always shine.

As for safety, there have been more than 100 accidents at nuclear facilities since the first nuclear power plant was constructed in 1951. But the extent of the destruction might be overblown in the public imagination. The worst nuclear accident in the U.S., which currently generates about 20 percent of its electricity from nuclear power, was the Three Mile Island disaster in 1979. Nobody was killed or injured. Subsequent health studies of people who lived near the nuclear plant did not find any evidence that radiation exposure increased cancer rates.

The 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster — which tilted some nations against nuclear power, even if only temporarily — caused one death from radiation. (In further support of this, animals that were exposed to chronic radiation near the disaster site do not show “significant adverse health effects as assessed by biomarkers of DNA damage and stress,” according to a study published October 15 in the journal Environment International.) By comparison, the evacuation of Fukushima caused 2,202 deaths “from evacuation stress, interruption to medical care, and suicide,” according to the Financial Times. Overall, the tsunami killed well over 20,000 people.

To be sure, leaked radiation from nuclear accidents can have lasting consequences. A 2006 study published in the International Journal of Cancer estimated that the 1986 Chernobyl disaster “may have caused about 1,000 cases of thyroid cancer and 4,000 cases of other cancers in Europe, representing about 0.01 percent of all incident cancers since the accident.”

But there is harmful fallout from fossil fuel facilities, too. Studies have shown that petroleum workers are at elevated risk of developing cancers like mesothelioma, leukemia, and multiple myeloma. Accidents in the fossil fuel industry are also far more deadly.

The three worst nuclear accidents in history — Chernobyl, Three Mile Island, and Fukushima — killed a total of 32 people. For context, that is roughly the same number of people that used to die every year in the U.S. coal mining industry during the early 2000s, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The combined death toll from those three nuclear accidents is lower than many individual accidents in other energy sectors, including:

- The 1980 Alexander L. Kielland accident, in which a Norwegian drilling rig capsized and killed 123 people.

- The 2013 Lac-Megantic disaster, in which a train carrying crude oil in Canada derailed and killed 47 people.

- The 2013 Sinopec Corp oil pipeline explosion in China, which killed 55 people.

Both the fossil fuel and nuclear power industries can be deadly, but the former has far more blood on its hands. (Other power production methods aren’t always safe, either. Among the deadliest energy-related accidents ever was the 1975 Banqiao Dam failure in China, in which a hydroelectric dam collapsed and killed more than 150,000 people.)

Most people want access to cheap energy that doesn’t harm the environment. But even though there are valid concerns about nuclear power, including how to dispose of radioactive waste, people who support climate goals while opposing nuclear power should consider where else their electricity will come from. In post-Fukushima Germany, it was mostly coal.

Until renewables become decidedly cheaper than and at least as reliable as fossil fuels, odds are that policymakers who choose to omit nuclear will cause more harm — both to workers and the environment.