Oil execs should be tried for crimes against humanity, essayist Kate Aronoff argues

Photo credit: SANDY HUFFAKER / AFP / Getty Images

- A new essay published in Jacobin argues that the time has come to try the executives of oil companies for crimes against humanity as a result of their actions promoting climate change.

- There is a legal precedent, as the heads of several German companies were tried for such crimes after WWII.

- Even if it never comes to pass, discussing the idea could give us a sense of what steps to make the world a greener place are possible.

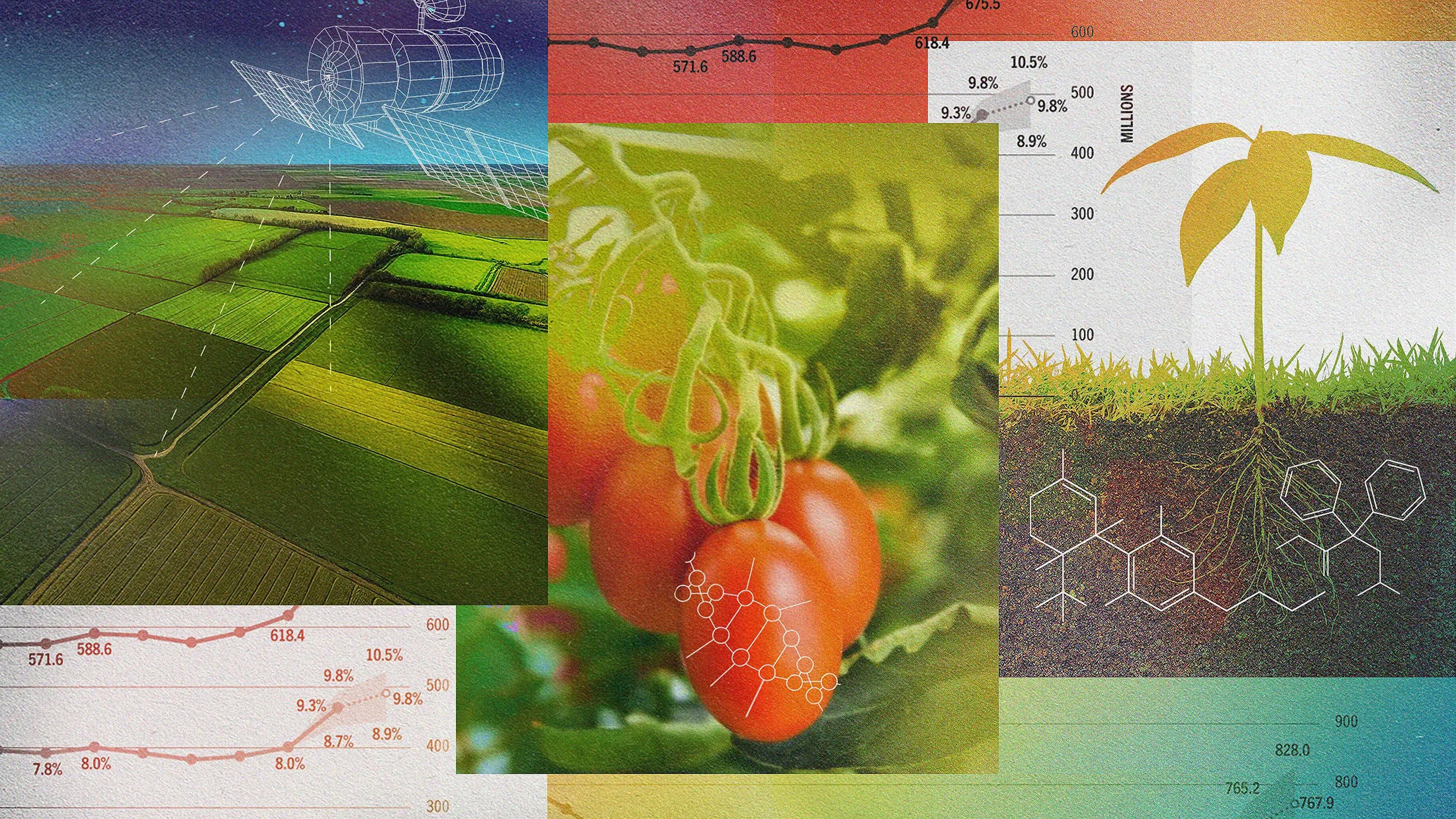

The threat posed by climate change is planetary in scale and deadly serious. Four hundred thousand people die each year from climate change-related causes. Natural disasters are getting worse because of it. The last five years have been the hottest ever recorded.

While there is a tendency to put the problem in terms so dark that people think the situation is hopeless, we’re not doomed just yet. If dramatic action is taken now, we can keep global warming under 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2050 and avoid the worst-case scenarios that climate scientists keep showing us. What form that action will have to take is still being debated.

One of the boldest suggestions for necessary action in the name of saving the planet was recently put forward by Kate Aronoff in an essay published in Jacobinmagazine in which she argues for trying the executives of all the major oil companies for crimes against humanity.

Wait, what?

The argument is intriguing, and the essay is written in a way that both properly handles the gravity of the problem while giving a glimmer of hope. While the idea it presents may seem shocking, it is presented with strong reasoning and should at least be considered.

It begins by reminding us that the 100 largest fossil fuel companies are responsible for 71 percent of all the greenhouse gas emissions since 1988. As mentioned above, 400,000 people die each year as a result of the climate change that these emissions cause, and the other side effects of burning fossil fuels, such as air pollution or cancer, may kill up to 5,000,0000 people a year.

The companies in question have known about the dangers posed greenhouse gas emissions since at least the late ’80s. Understanding the risks and environmental damage their business model creates, they have spent millions upon millions of dollars to discredit climate science and prevent regulations designed to limit the damage they cause. The resulting damage has already been astronomical and could soon become uncalculatable.

Their actions could qualify as a crime against humanity under the broad definition of the term; which merely requires knowledge of and involvement with actions which systematically attack a civilian population. The idea of a company’s executives being tried for such a thing isn’t as crazy as it sounds since the people who made gas for the Nazis were tried for their part in the Holocaust after WWII.

Given the seemingly obvious point that the companies that have done these things to deny climate change and prevent strong environmental regulations probably can’t be trusted to fix the problem themselves. Ms. Aronoff, therefore, calls for legal action against the companies and the people who are running them as a way to not only halt the destruction they are wreaking upon the environment but also to break the power they often hold over policy-making through litigation and public denunciation.

Even if this never comes to pass, which the author admits is probable, the mass public movement that would be needed to even place this option on the table could bring other environmental policies into play. This is the long-term goal anyway, she argues, and the discussion of whether oil company executives committed crimes against humanity might be enough to reduce their influence even without indictments.

For those who would like to read the essay in its entirety, it may be found here.

Cutting out influence

Tobacco companies aren’t allowed anywhere near World Health Organization meetings for reasons that should be obvious. However, oil and gas companies have their fingers all over the regulatory codes and international treaties that are supposed to limit their activities. According to Ms. Aronoff:

“At COP 24 last year in Poland, GasNaturally cohosted a cocktail hour with the European Union, and Shell bragged about its influence in grafting a whole section onto the Paris Agreement. The Polish coal sector was a main sponsor of the whole event….. Stateside, advocates of certain forms of carbon pricing…. have boasted of garnering support and funding from the likes of Exxon and BP, apparently a marker of their respectability.”

She calls this “an atmosphere of impunity for atrocity” and argues that we should at least be keeping fossil fuel companies out of such meetings and policy discussions if we aren’t prosecuting them.

The time corporate executives were tried for crimes against humanity before

Believe it or not, there is a precedent for the idea that a company’s executives can be tried for crimes against humanity.

The heads of the German chemical conglomerate IG Farben were tried at Nuremberg for participation in the Holocaust with their production of Zyklon B- the gas used to carry out the Holocaust. They were also tried for the use of slave labor and for preparing to wage an offensive war.

The results of trying them were mixed, only half of them were found guilty of any of the various crimes they were tired for and the worst any of them were sentenced to was eight years minus time served. Even more disappointingly, most of them returned to cushy executive jobs in critical sectors of the German economy when they got out. However, the convictions demonstrate the legal precedent of viewing a company as being every bit as capable as a state when it comes to crimes against civilian populations.

Two other trails were held for German industrialists who made the crimes of the Nazi regime possible, the results were again mixed and the sentences often limited.

The oil wars: America’s energy obsession

Name and Shame

Ms. Aronoff argues that many of the major players in fossil fuel companies are relatively unknown. She sees this as a problem because it makes the issue abstract and more difficult to conceptualize. By dragging real people into courtrooms, a face is given to the problem and real people are punished for actions which harm millions of people.

Even if such trails were to lead to limited convictions or the convicted were able to still hold cushy jobs after serving their sentences, the fact that executives could be tried and sent to prison for various crimes could be an excellent motivation for anybody working in the energy sector who wants to avoid being convicted of crimes against humanity to start behaving themselves. After all, how much profit is worth being dragged to The Hauge over?

Sometimes you don’t need to win to win.

The various legal difficulties of accomplishing this are described in the article, not the least of which is that the United States is not a signatory to the Rome Statute which established the International Criminal Court. However, this might not be terrible.

Ms. Aronoff argues that the real goal of any mass environmental movement should be the decarbonization of the economy. While trying oil executives might be a way to achieve this, it is not the end itself. Any mass movement that was able to apply such pressure on governments to put the idea of trying these executives for crimes against humanity on the table would likely be able to bring other bold ideas on how to make the world greener to the table.

As neuroscientist David Eagleman explains, putting out an idea that might never catch on is a great way to figure out what ideas can work. Even if the idea of putting the c-suites of major corporations on trial never takes off, just discussing it can help us determine what could.

How realistic is any of this anyhow?

Therein lies the problem.

As the author explains in the essay, several institutional issues pop up when discussing the question of just how to carry out the idea; not the least of which is that the ICC is designed to go after state actors, not corporations. While it is possible that individual countries could carry out the task, this is also a legal minefield.

The question of political will is also important, given that many of the largest oil companies in the world are also primary revenue sources or owned by states that depend on them doing well. The idea that the Saudi government would go after the executives of their national oil company, which is reasonable for 3.5 percent of all carbon emissions since 1995, is absurd. The potential for a mass movement in a democratic society demanding the executives be brought to justice is possible, but it would face a wall of opposition from the people who both deny climate change is happening or oppose bringing corporate executives to trial over it.

In any case, the mere introduction of this idea to the public debate should have far-reaching consequences on how we consider correcting for a century of greenhouse gas emissions. While we may never see Rex Tillerson standing trial for egregious pollution, we could still manage to mitigate the worst effects of climate change. In the end, isn’t that what matters?