COVID-19 is accelerating the pace of automation and the need for UBI

Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

- The coronavirus crisis has acted as a catalyst for two powerful transformative forces: automation and universal basic income.

- These two intertwined forces will undoubtedly gain steam, writes Frederick Kuo, and the pandemic will hasten the acceptance of them from a scale of decades to years or mere months.

- This crisis has ushered in a glimpse of what a dystopian future could look like as a rapidly advancing fourth industrial revolution inevitably causes severe disruption in our economy and labor structure.

The coronavirus pandemic has sent the global economy into a tailspin posing a twisted choice to humankind between economic survival or our very health. Markets are crashing, numbers of infected people and deaths soaring by the day and a massive part of the global economy forced into a standstill as people shelter in place. Looking out the window, the world still looks the same. The sun is still shining, the leaves still rustle in the wind and birds still chirp merrily as if nothing was amiss. However there is no mistaking a collective sense of mourning that the world is feeling as normal daily routines and freedoms we took for granted have come to a sudden halt. Amidst the constant barrage of gloomy news however, this crisis shall inevitably pass. But the world post-COVID-19 will not be the same; the crisis has acted as a catalyst for powerful transformative forces such as automation and the need for universal basic income, two intertwined forces that will undoubtedly gain steam.

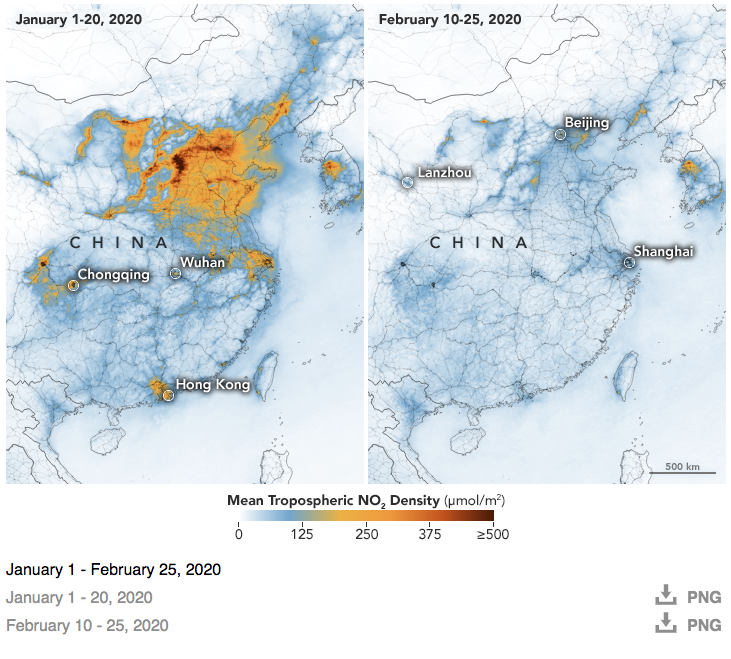

As the mobility of human beings grinds to a halt due to public health directives and fears of infection, our need for food, resources and social connection has forced us to increasingly rely on technology to fill urgent gaps. In the United States, Amazon is seizing this opportunity to further entrench its domination, while in China, robots are being deployed to serve those in quarantine. In a world where fear of contact with other humans has become pervasive, businesses that can adapt quickly and significantly automate their supply lines and cut points of human contact stand to thrive in this new market.

Whereas before this crisis, the need for automation was mainly driven by the desire for increased profits and improved efficiency, the momentous shift in public consciousness today regarding simple human contact may make automation almost a necessity for many businesses to survive. When humans trust a robot to handle or deliver their food or goods more than they trust another human, or when crowded workplaces present public health hazards, jobs for humans will be unceremoniously eliminated. Given existing technologies, experts have estimated 36 million jobs may be vulnerable, ranging from trucking and delivery to food service and repetitive white collar jobs, the labor market may face a significant restructure driven by new technology and a radically altered market for those technologies. In a recent survey conducted by auditing firm Ernst & Young, more than half of company bosses throughout 45 countries had begun implementing existing plans to fast track automation.

This crisis has compacted the timeline of a gradual acceptance of an automated future from years into months.

The crisis of unemployment has become real for tens of millions locked down around the world. Although this phase is likely to be temporary with normality expected to return by the third quarter, the process of entrenching automation in our daily lives will be radically pushed forward. This crisis has compacted the timeline of a gradual acceptance of an automated future from years into months. In Seattle, Amazon has pioneered Amazon Go, a small grocery that relies on cameras and sensors to charge customers for what they buy instead of a checkout line. With Amazon already in control of a major grocery chain, Whole Foods, one could imagine that this little, fully automated store could serve as a template for a nationwide expansion of this technology, thus reducing the once-vital role of the cashier nearly overnight. Similar rollouts of automation models will likely follow in the coming years, affecting warehouse employees, delivery people, food service personnel and more.

Universal basic income: The plan to give $12,000 to every American adult | Andrew Yang | Big Thinkwww.youtube.com

In early 2019, Andrew Yang began gaining news coverage regarding the central theme of his presidential campaign: $1,000 a month in universal basic income (UBI) dispersed to every American. His primary argument for the necessity of this safety net rested on the belief that the coming age of automation was about to inundate vast scores of our current jobs with a shrinking percentage of elite tech corporations gobbling up more and more of the profit. When Yang first introduced his vision, it seemed to belong to a remote dystopian future with little relevance to the booming economy and low unemployment figures that was the reality until only weeks ago. On the right, he was lambasted as a communist seeking to turn American citizens into dependents to the state. On the left, his ideas were dismissed as other Democratic hopefuls touted the Green New Deal and job programs.

Fast forward to today and Andrew Yang’s UBI theory has moved straight into the forefront. Trump, perhaps cognizant that the “Yang Gang” pulled a great deal of support from his own supporters, quickly recognized the popularity of his ideas and the need to provide supplemental income to Americans as shelter-in-place directives began to take hold throughout the country. The massive $2 trillion coronavirus emergency stimulus will provide every American earning $75,000 or less, regardless of current employment, a check of $1,200 per person and $500 per child for the duration of the crisis. There has been little debate over the necessity of this measure because it has proven to be widely popular to the public, regardless of political standing. It lifts some of the immediate and pressing need to work and helps take some of the edge off from isolating at home, thus contributing to a quicker resolution of this health crisis by sending fewer people out into the streets.

Although the pandemic and the stimulus check is temporary, this crisis has ushered in a glimpse of what a dystopian future would look like as a rapidly advancing fourth industrial revolution inevitably causes severe disruption in our economy and labor structure.

Although the stimulus package is a stopgap measure to deal with this crisis, its absolute necessity during this crisis has validated Yang’s prophetic vision of a dystopian future where work no longer becomes possible for huge swathes of the American people. The reality is that the after effects of this crisis will be felt for at least months after the pandemic ends. There is little security for either the business owners or employees of food service businesses, bars, hair and nail salons and essentially any business that requires large crowds of people to gather and interact. To the initial detractors of UBI who argued that the program would breed laziness and a welfare state, the reality is that for most workers thrown into the sea of uncertainty, receiving a stimulus check will provide a small lifeline but will ultimately be of little solace to individuals who are accustomed to earning far more and who derive a sense of pride and satisfaction from their jobs. For most of those impacted by loss of employment, supplemental income in the form of a UBI helps take the edge off but it is ultimately no replacement for having a job or business.

Although the pandemic and the stimulus check is temporary, this crisis has ushered in a glimpse of what a dystopian future would look like as a rapidly advancing fourth industrial revolution inevitably causes severe disruption in our economy and labor structure. Automation and artificial intelligence are coming and will significantly alter the way we work, shop, eat and socialize. As society experiences the disruptive force of technology and draws on our collective experiences fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, UBI may become a permanent fixture of our political economy as well.