The horrifying problem of meaning

- More than any other concept, there’s something about inquiry into the notion of meaning — and meaninglessness — that is especially unsettling. How do we know that our lives, with all our loves, ambitions, and fears, have any meaning at all?

- Various theories about meaning draw on concepts from biology, information theory, and the multiverse.

- All of us experience a world haunted by meanings. Whether we exorcize the ghosts or succeed in explaining them, our familiarity with the world and ourselves cannot survive.

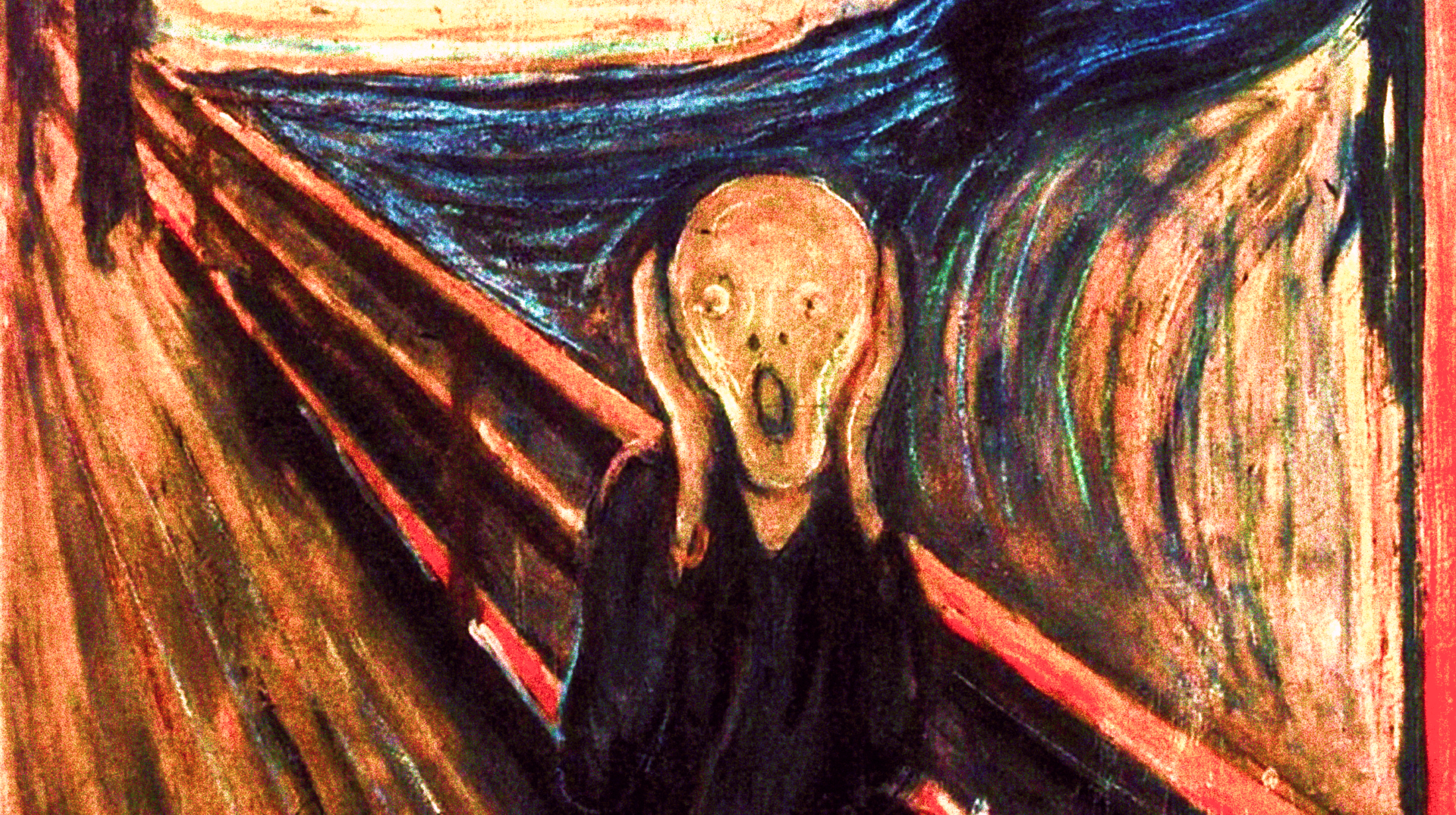

Terror is something you can run away from. It’s the fight-or-flight sensation that builds as a dreaded encounter draws near. Horror, by contrast, is inescapable. You glimpse something that cannot be unseen, and in an instant, you realize that the familiar has been harboring something strange — that the thing you hold close is not what you thought it was.

Philosophy presents many opportunities to feel the delicious thrill of horror because it asks us to peel back the layers of ideas we take for granted and confront whatever is concealed within their core. How can we be individuals who preserve an identity for a lifetime when our bodies contain immense networks of foreign organisms, and everything about us, from our cells to our beliefs, transform over time? How should we judge whether an act is right or wrong when there are so many different theories about how behavior gains ethical valence?

The meaning of meaning

More than any other concept, there’s something about inquiry into the notion of meaning — and meaninglessness — that is especially unsettling. How do we know that our lives, with all our loves, ambitions, and fears, have any meaning at all?

Meaning seems ubiquitous. People’s thoughts, utterances, and writings possess meaning. Portraits and maps represent people and places. Deer tracks in the mud carry information about deer movement, and variables in mathematical equations can refer to numbers. Are all these examples different versions of a single underlying phenomenon?

Thinking about the problem of meaning is unsettling because it takes something intimately tied to our lives, highlights our ignorance about it, and introduces us to a list of solutions that all feel a bit insane.

Many people who have spent a lot of time thinking hard about the problem of meaning think so. But consensus ends quickly. Despite thousands of years of inquiry, no one really knows what meaning is or how it works. There isn’t even consensus about how to think about how meaning works. If someone in a pessimistic mood were introduced to the legacy of work on this problem, they could be forgiven for concluding that humanity lacks some necessary insight or tool that would allow us to puncture the skin of meaning and begin peeling back its layers. Nevertheless, people who have devoted themselves to understanding meaning generally converge on what I’ll call the iceberg analogy.

The iceberg cometh

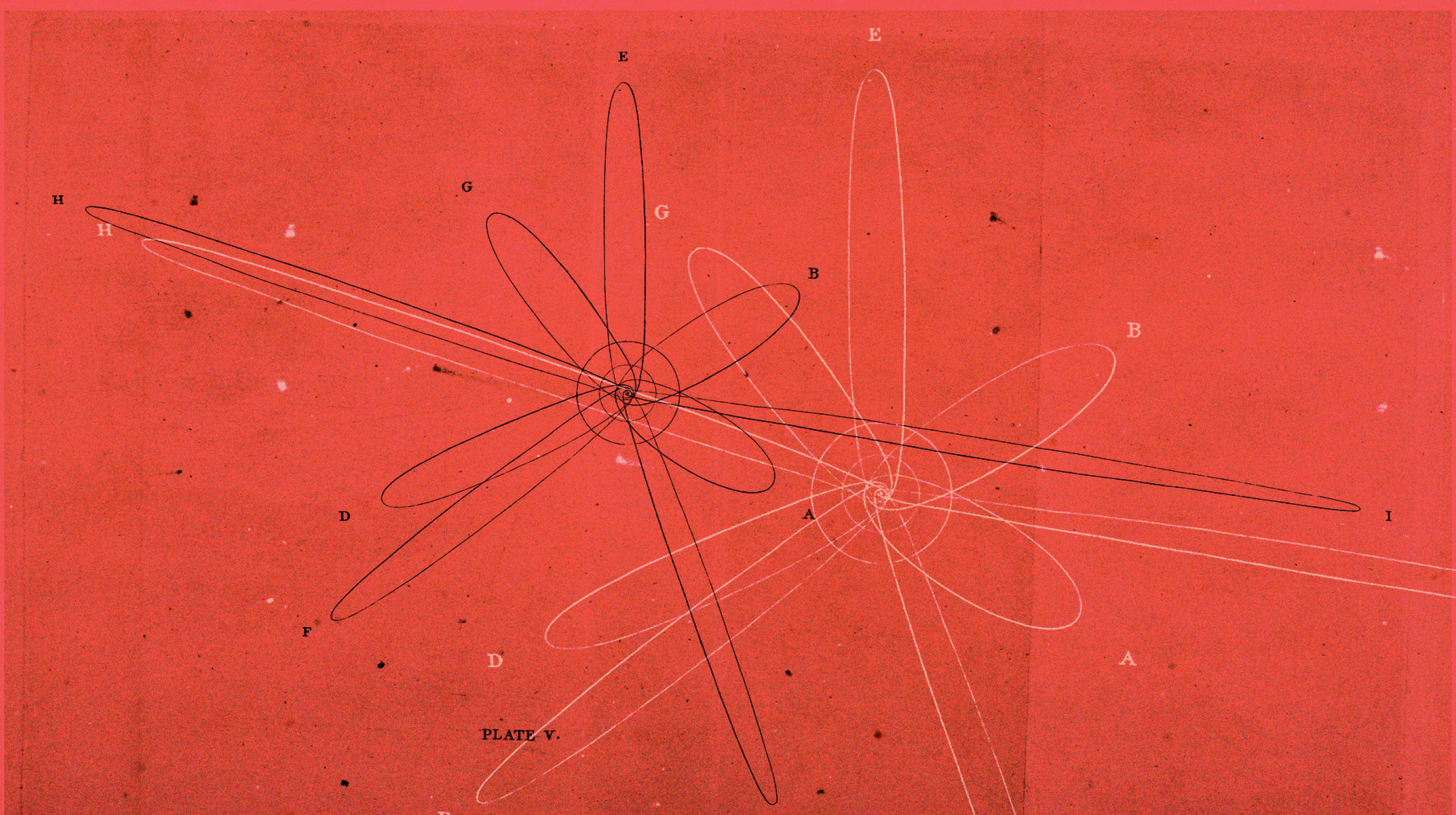

The thrust of the iceberg analogy is that the meanings we observe and interact with are not the whole of meaning. Rather, every instance of meaning is like the exposed tip of an iceberg. Beneath the surface, each tip extends into an enormous supporting mass, and these masses are somehow responsible for imbuing the observed world with meaning and determining what those meanings are about.

Imagine you find a wallet on the sidewalk. You open it, pull out an ID card, and interpret the markings as representing the owner’s face and name. According to the iceberg analogy, you have brushed up against a hidden world that makes your act of interpretation possible. What iceberg theories of meaning disagree on is what sorts of things, processes, or forces constitute this hidden world.

In the 20th century, many thinkers came to see Western analytic philosophy as uniquely suited to the task of explicating the implicit rules and conceptual relationships guiding people’s use of language. Joining this linguistic turn, many influential theories of meaning from the last century or so focus on explaining the meanings of words and sentences in terms of the way people use language. If the tip of an iceberg is an instance of language, then these use-based theories maintain that the submerged mass is full of people doing things with that piece of language. Different theories tell different stories about who these people are and what exactly they’re doing. For example, some theories say the base of the iceberg contains different versions of the person who invoked the piece of language at the tip of the iceberg.

Let’s pump the brakes. It’s easy to nod along without really imagining what it would take for these theories to be true. To begin, we need a framework for imagining how the different ways different versions of yourself might use a word could determine the meaning of a word you actually use. One powerful way of imagining such possibilities is to envision different versions of yourself actually using a word, like “dog,” in those different ways in different universes. The multiverse has become a popular plot device, so the idea of an infinite number of internally consistent universes across which all possible things eventually happen may not feel so strange. What remains strange is the idea that some of these universes, or as philosophers like to say, possible worlds, affect the meanings of things here in our world. If we abandon the multiverse framework, the kernel of strangeness within counterfactual use-based theories of meaning remains because such theories imply that meaning is shaped by the ways people might act. It is as though the meanings of our words are shaped by shadows of what could be.

Looking to science for meaning

Just as strange but broader in scope, some theories aim to explain all forms of meaning, not just language. Trees communicate through underground root networks, animals’ sensory organs represent features of the environment, and DNA is supposed to contain information about how to build an organism. When philosophers step back and try to provide a common foundation for these diverse meanings, they find solid ground in different places.

Some look to biology. Scientists gave the idea of natural selection a solid basis in the 20th century by integrating theories of evolution, inheritance, and molecular genetics. This achievement, often called the modern synthesis, appeared to provide a unifying framework for thinking about life. Since then, some philosophers have sought to use this framework to explain meaning in living systems generally. For these natural selection theorists, the tip of the iceberg is a trait that deals in meaningful content, like the color patterning that makes moth wings resemble a giant pair of eyes. Natural selection theorists have a complicated story to tell about how basic forms of meaning can build on each other over vast stretches of evolutionary time to eventually produce more sophisticated forms of meaning, like human language. The central idea motivating natural selection theories, however, is simple: Biological functions are the basis of meaning.

When moths are eaten, biologists don’t say that moths died because their pseudo-eyes failed to have a function. They say that the pseudo-eyes failed to perform their function. Meaning relationships seem to work the same way. If the concert starts at 9 pm and I tell you, “The concert starts at 7 pm,” then my statement doesn’t lose its meaning. It just fails to accurately represent reality. According to natural selection theorists, biological functions persist through failure because they are fixed by history. The pseudo-eye trait has the function of scaring away predators because that is the outcome that allowed the moth’s ancestors to pass on the pseudo-eye trait. Extending all this to the iceberg analogy, natural selection theories maintain that the hidden base of the meaning iceberg is full of ancestors confronting the world and meeting their fates across deep time.

But biology isn’t the only area of science that feels relevant to meaning and enjoyed a 20th century breakthrough. At the end of WWII, mathematicians and communication engineers developed a mathematical theory of communication called information theory. The immediate motivation for such a theory was to understand the limits of electrical communication technologies, like digital computers, so that they could be optimized. This sort of thinking led scientists to uncover a profound relationship between communication systems, entropy, and the second law of thermodynamics.

It’s easy to see why philosophers seeking solid ground to build a general theory of meaning would be drawn to a mathematical theory of communication that’s tied to a law of physics. The problem is that although information theory assumes meaning exists, it completely side steps the problem of meaning. That may sound odd since meaning feels so integral to communication. But information theory showed that one can usefully analyze communication systems with metrics that say nothing about the meanings of messages. Information-theoretic philosophers are searching for a way to extend the conceptual machinery of information theory into the domain of meaning.

It’s unclear how to do this, so the meaning iceberg for information-theoretic accounts is especially murky. Whatever is going on, it’s likely to have a technocratic sheen. The basic framework of information theory starts with a sender who has a collection of messages they could send with different probabilities. The sender picks a message, encodes it into a signal, sends the signal via a channel to the receiver, who then decodes the signal to reconstruct the message. Put in these terms, it may seem like the theory only applies to people using modern technologies to communicate. However, it can be applied much more broadly so that the sender is an eye, for example, and the receiver is a brain. So, the tip of the iceberg might be a message-encoded signal traveling through a channel. The submerged base could involve meaning-agnostic information metrics like “bits,” or something else related to all the possible messages the sender might have sent, or perhaps there’s something about the act of encoding and decoding signals that can be used to explain meaning.

The horrifying problem of meaning

So far, I have only given a peek into three flavors of meaning theory. There are many more that differ radically. Yet just within this small 20th century cohort, it’s already difficult to specify where different theories complement or conflict with one another. Philosophers have the freedom to mix and match disparate theories of meaning because there is so little to constrain their theorizing. How would one produce evidence bearing on any of the theories surveyed above? If one of the theories were true, what implications would it have for other areas of inquiry that assume a meaning-saturated world, like anthropology, sensory physiology, or machine learning? We are still waiting for knock down arguments.

Thinking about the problem of meaning is unsettling because it takes something intimately tied to our lives, highlights our ignorance about it, and introduces us to a list of solutions that all feel a bit insane. Even if we harden our hearts and renounce the idea of meaning as a chimera sustained by some perverse bend of the human mind, we cannot escape the horror. All of us experience a world haunted by meanings. Whether we exorcize the ghosts or succeed in explaining them, our familiarity with the world and ourselves cannot survive.