In the age of the child prodigy, many believe that whoever gets ahead first, stays ahead. But journalist David Epstein doesn’t buy it. He argues that slower development, contrary to popular belief, often results in more success in the long run. Human development doesn’t always follow linear progressions, making it critical to have a broad training base and conceptual framework.

To illustrate this, Epstein tells the story of Gunpei Yokoi, a Nintendo machine maintenance worker who ended up creating the Game Boy console, the bestselling console of the 20th century. Yokoi’s philosophy of “lateral thinking with withered technology” led him to his genius invention — not through specialized knowledge or skill, but through adaptability.

In an environment where information is widely available, having a broad view and drawing on different stores of knowledge is essential. By adopting a short-term mindset and being a generalist, individuals can develop the skills necessary to thrive in a highly specialized, rapidly changing world.

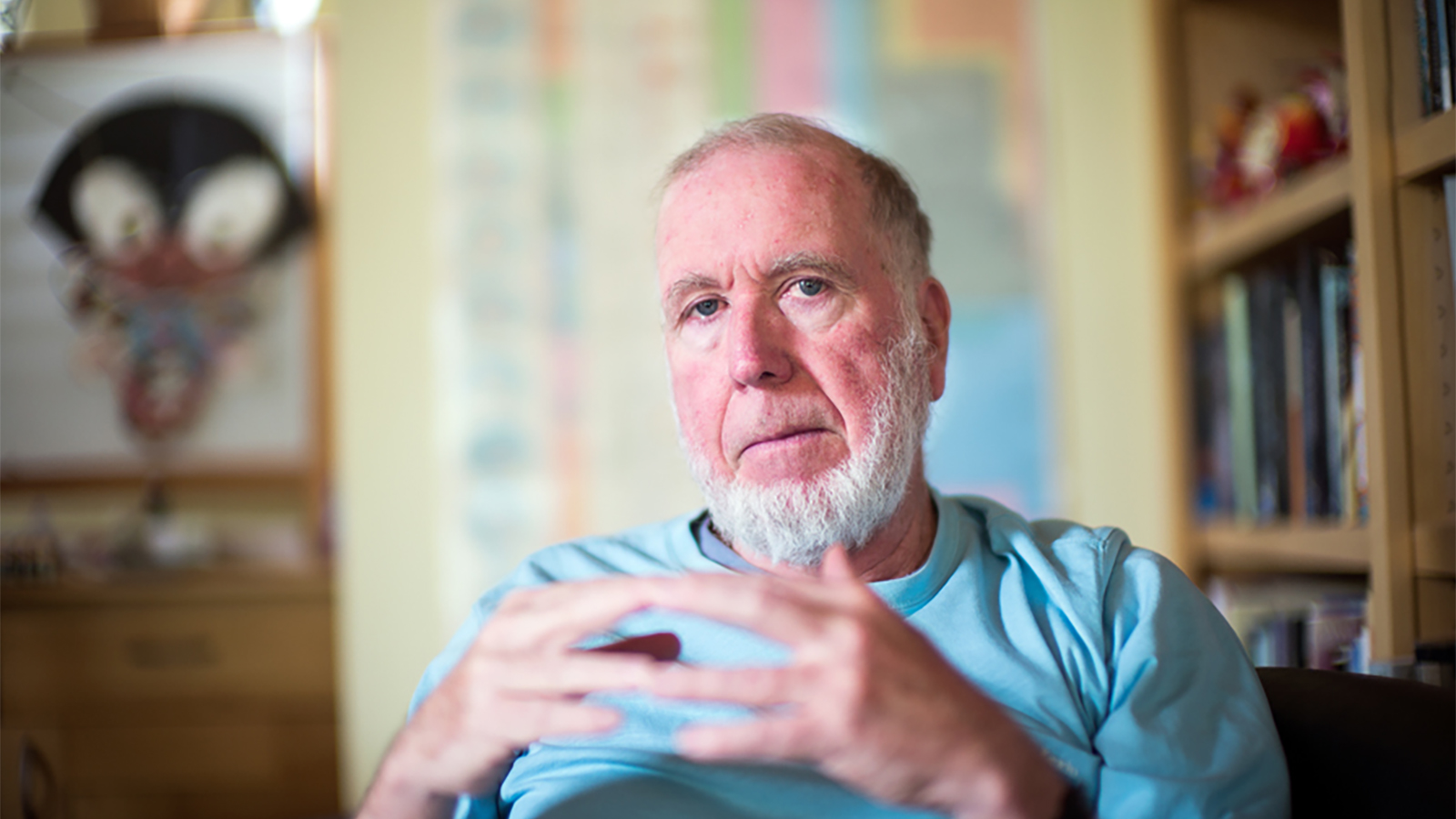

DAVID EPSTEIN: Child prodigies, especially in the YouTube age, are sort of like human cat videos. Whether they're playing classical music or they're in a sport or playing chess, you can't look away from them, they're so entertaining. We think of that as a trajectory. If they're this good at age five or age 10, they're gonna be so good at age 20 or 30 or 40. And I think the idea that parents tend to take from them is that if I just give my kid this very narrowly focused, early, technical training, my kids will be ahead and they'll stay ahead forever. It's just the problem is that turns out not to be the case. I'm David Epstein, author of "Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World."

CAMERAMAN: Nice, bro!

EPSTEIN: Okay, so even if you don't know the details of Tiger Woods' story, it's probably the most powerful modern story of development. His father gave him a putter when he was seven months old. At two years old, he was on national television showing off his swing in front of Bobe Hope. At three, he was learning how to play out of a "sand twap," as he put it at the time and saying, "I'm gonna be the next great golfer. I'm gonna be the next Jack Nicholas." By the time he's a teenager, he's famous. And you fast forward to age 21 and he's the greatest golfer in the world. I think one of the reasons that prodigy stories are so attractive is because we're used to thinking of everything as being a trajectory, right? It's intuitive to want to give a kid a headstart. In sports, that might be something like learning how to run certain types of plays or very specific techniques. Or in music, how to play the same piece over and over and over again. Or in academics, tricks for working out math problems. The problem is, we don't follow linear progressions. We are not wired correctly to interpret our own development, necessarily, 'cause we just want what comes the fastest when, in many cases, slower development is actually the best in the long run.

One way to think about the world is to think of it as a learning environment, and the milieu in which you have to develop some kind of skill. They run on a spectrum from kind learning environments where what you have to do is very clear and delineated by clear rules and patterns repeat and the task doesn't change, all the way to wicked learning environments where information might be obscured, there are no discernible rules, the work can change and even the feedback you get can be delayed and inaccurate. And we only see those prodigies in these very kind learning environments. You can think of something like chess. The grandmaster's advantage is essentially based on recognizing recurring patterns. But most of the work we do these days is more toward the wicked end of the spectrum, where we can't just count on things being the same over and over or giving us perfectly accurate feedback. For the wicked world, you want a really broad training base, what scientists call a sampling period, where you're forming conceptual frameworks and abstract ideas that you can bend to the activity as the activity itself changes.

For a lot of the 20th century, the biggest contributions came from specialists. But in the information age, as more information became quickly and easily disseminated, it became easier to be broader than a specialist and the biggest contributions started coming from people who spread their work across a large number of technological domains, often taking something from one and bringing it to another area where it was seen as extraordinary, even if it was more ordinary somewhere else. (playful music)

Gunpei Yokoi was a Japanese man who didn't score well on his electronics exams in university so he had to settle for a low-tier job as a machine maintenance worker at a playing card company. This playing card company, founded in the 19th century, is called Nintendo. And one day, the president of the company saw Yokoi essentially playing around with company equipment 'cause he didn't have anything to do and he made an extendable arm called the Ultra Hand. It was just a device where you could grab distant objects with suction cups. And the desperate president says, "turn that into a toy, we're going to market," and it's sort of a success. And so the president says, "all right, you're going to start a game and toy operation." Yokoi realizes that he's not equipped to work on the cutting edge, but there's so much information widely available that he can take information from different domains and merge it, and he did that for his magnum opus, the Game Boy. He developed this philosophy he called lateral thinking with withered technology. And what he meant by that, withered technology, he meant technology that's already well understood, easily available and often cheap, and lateral thinking meant taking it from an area where everyone's already used to it and merging it with something else. Because the technology was so withered and so well understood, programmers inside and outside of Nintendo pumped out games for it way faster than their competitors and the Game Boy became the best-selling console of the 20th century and Nintendo still uses that lateral thinking with withered technology philosophy today.

The more we work in a rapidly changing world where we're not exactly sure what we should do next or what work will look like next year or in five years or 10 years, the more we want those people who have had a broad view and can kind of draw on different stores of knowledge. And one of the ways I think about operationalizing that is essentially having a short-term mindset. I know that sounds bad, right? You tell people we should have long-term goals and that it's like the commencement speech advice, "who are you gonna be in 10 or 20 years?" and "march toward that." It turns out that's not really a good way to operate, especially when you're younger. We're essentially telling someone to choose for a person they don't yet know who's gonna be working in a world they can't yet conceive. The main advice, if I judge by what people say back to me, is to not feel behind because you probably don't even know where you're going, anyway. And I think, rather than comparing yourself to someone who isn't you, you should compare yourself to yourself yesterday and proceed that way.