- With so much chaos in the world, it is tempting to embrace the adage, “Ignorance is bliss.” But, what if it’s actually the opposite?

- Many scientists would argue that knowledge, understanding, and enlightenment are always better than ignorance. Why?

- Because the more we know about the world, the better we understand the interconnectedness of nature and mankind and how the universe is full of magic and wonder.

JIM AL KHALILI: A lot of people think that somehow gaining knowledge about the world and how the world works detracts from its mystery, detracts from its beauty. Ignorance is bliss: quite the opposite. The more we understand, the more we can appreciate, the more we can find wonder; whereas remaining in ignorance, that's just darkness, that's just confusion. Knowledge, understanding, enlightenment are always better than ignorance.

My name's Jim Al-Khalili. I'm a professor of physics at the University of Surrey. My most recent book is called "The World According to Physics."

I tend to think of our knowledge of the Universe and of reality like an island- the interior of the island is the well-established science that we know very well. The shoreline around the island, that's the limits of our understanding, and beyond it, is the ocean of the unknown. Of course, we don't know whether that ocean goes on forever. As we gain in our knowledge and our understanding, the island is growing in size. So we're reaching out. We can take a paddle out into the water to see some of the mysteries that we're trying to tackle now that we still don't understand. But we don't know how much further our understanding needs to go. There are certain questions that we have always asked about ourselves, about the world, that transcend science.

They're certainly the big questions in science today, but they've been questions we've been asking for millennia. "Who am I?" "Where is my place in the universe?" "What is the nature of self?" "Where did we come from?" They may be questions that we'll never find answers to. But that is the nature of humanity, the nature of humankind; that we want the answers to some of these deep questions. There's this notion that somehow scientists have this sterile, clinical, logical, rational view of the world that leaves no room for mystery and awe and magic and wonder. On the contrary, everything I learn about how the world is tells me it's full of magic and wonder. The idea that Newton discovered that the invisible force pulling the apple down to the ground is exactly the same force keeping the moon in orbit around the Earth is utterly profound; it's utterly awe-inspiring.

I remember, as a student, sitting in a lecture being told about the equations of electromagnetism; the professor wrote down equations on the board. He went through lines of algebra and arrived at a new equation, and in that equation was a number. And he said, "And that is the speed of light. And that tells you that light is an electromagnetic wave." I remember sitting there, and, you know, even as I'm telling you this now, I have that same shiver going down my spine. There's wonder wherever we look- it's the opposite of sterile, rational, cold, analytical thinking. It's often said that the more we know about the workings of the Universe, the more we don't know. So our growing understanding really tells us about our growing ignorance. That is not to say that we haven't come a long way. We do know a lot about the building blocks of matter, about the nature of space and time. We now know how many elements there are that make up the world. We have the periodic table of elements. We now know why those elements are classified the way they are; because of the way electrons arrange themselves around atoms. The rest you could argue is down in the fine nitty-gritty detail. And it may well be that some of the ideas we have today, turn out to be wrong. Ten, twenty years from now, I probably wouldn't be saying something too different to what I'm saying today. But 100 years from now, and certainly 1,000 years from now, I may look back on the Jim of the early 21st century and think that I was just as naive as the medieval scholars who thought the sun orbited the Earth.

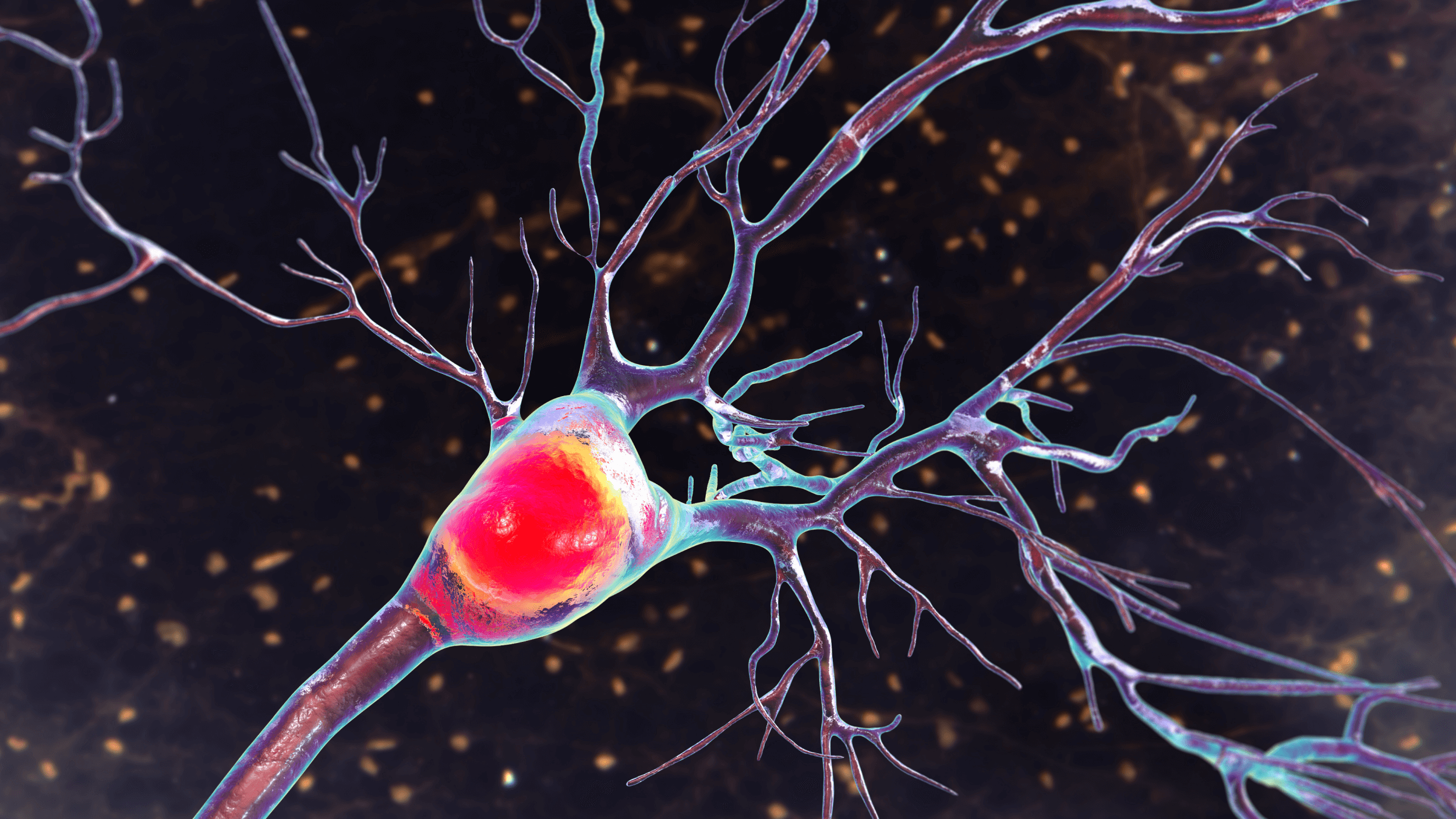

I think a lot of scientists are realizing that having this silo mentality of having expertise in one field to address some of the big questions, simply isn't enough. We're getting ever more interdisciplinary. I'm a physicist, so I would argue that physics is, of course, the best way of learning about the world. It's an arrogant view, and I think it's not exactly true. It's not going to address questions, like complex human behavior in society, or psychology or the workings of the human brain, but it addresses these fundamental questions: What everything is made of, how everything works. We don't know whether we will ever one day know everything about the nature of reality. And in a way, that's nice, that's exciting. It's frustrating, yet beautiful, that we may never have all the answers. There's this wonderful quote by Douglas Adams: "I'd take the awe of understanding over the awe of ignorance any day."