Are you a spectator to reality? Or are you its creator?

- If a tree falls in the forest and nobody is there to hear it, it really does not make a sound. What you experience as sound is constructed in your brain.

- You cannot experience the world, or even your own body, objectively.

- By seeking out new experiences, your brain teaches itself to craft new meaning.

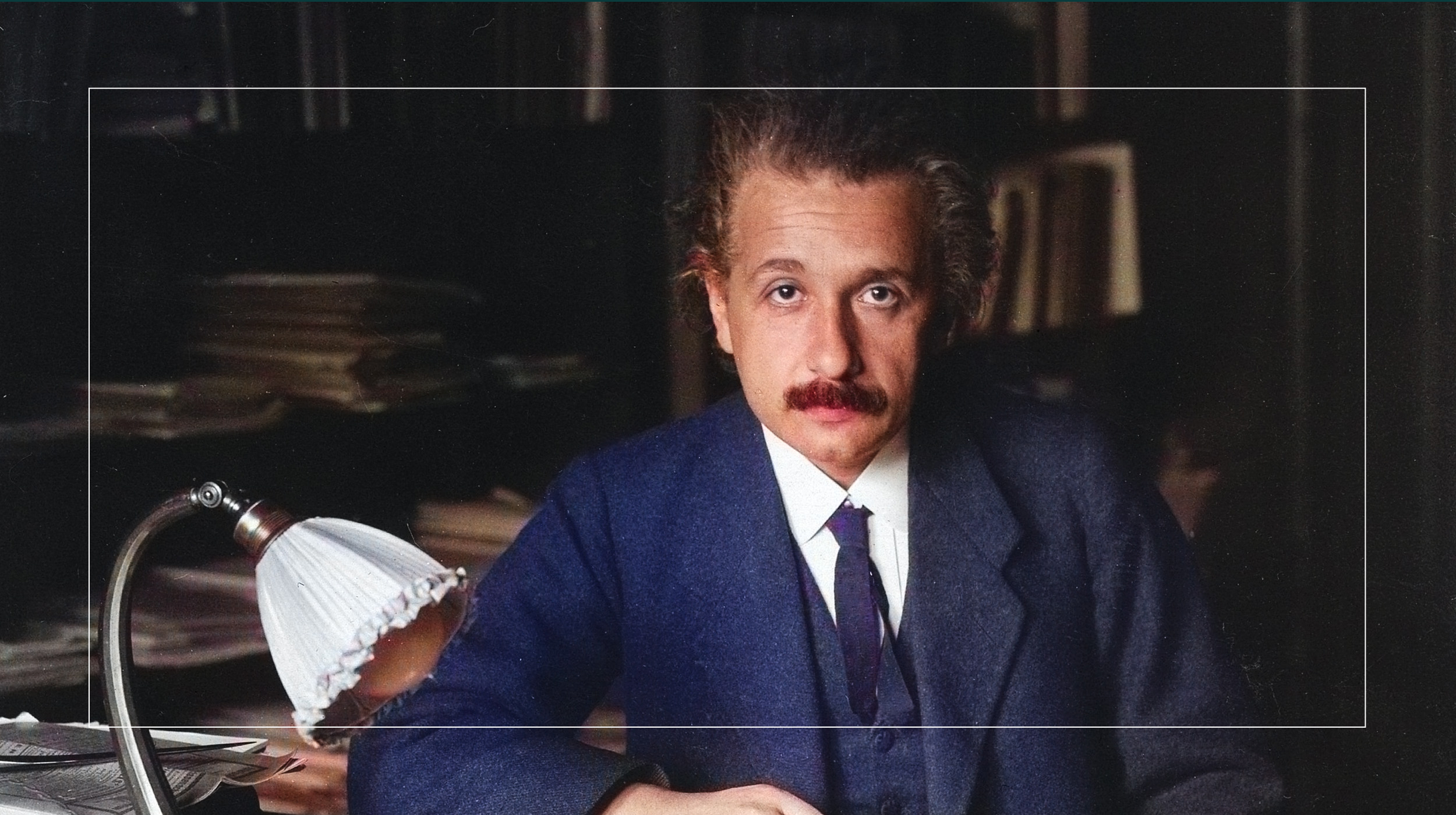

This year’s World Chess qualifying tournament brought a new twist: the heart rates of the players were broadcast live, with the help of AI software, so viewers could (supposedly) gain insight into the players’ emotions during a match. But can emotions be detected from mere heartbeats? When your own heart pounds wildly in your chest like a sledgehammer, does it necessarily mean you’re frightened? Angry? Excited? Full of joy? What if you’ve just finished a strenuous workout or knocked back a bit too much espresso?

When it comes to the question of what your heart rate means, psychologically speaking, the scientifically correct answer is: it depends. That’s because physical signals from within your body have no inherent psychological meaning. A particular heart rate does not indicate any particular emotional state. It’s not the case, say, that 100 beats per minute is happiness and 150 beats per minute is anger. The pounding in your chest during instances of both emotions can be physically identical. More specifically, your heart rate may vary just as much among different instances of anger as it does between instances of anger and happiness. Ditto for every spurt of cortisol, every trickle of dopamine, and every other electrical or chemical change in your body. What differs is the meaning that your brain makes of the physical signals in a particular context.

Physical signals have no inherent psychological meaning

The same is true of physical signals from the outside world. When a tree falls in the forest and slams into the ground but no one is present, it does not make a sound. It does produce a change in air pressure. That change becomes meaningful to you as a sound only when it reaches sensory surfaces inside your ear (your cochlea), producing a different physical signal that travels to your brain, where it meets an ensemble of other signals that represent your knowledge of falling trees and what they sound like. You don’t hear with your ears; you hear with your brain. If that same change in air pressure encounters your rib cage rather than your cochlea, you may feel a thudding in your chest rather than hear a sound.

Light waves similarly exist in the physical world, whether or not a human is present. But “color” is a feature constructed as your brain weaves those signals together with others of its own creation. So a statement like, “The rose is red,” is more precisely stated as, “I experience the wavelengths of light reflecting from the rose as red.” The redness isn’t in the rose. The light waves detected by the sensory surface in your eye (your retina) modulate signals along the optic nerve that encounter other signals in your brain that reassemble past experiences and give those incoming signals psychological meaning — and voila, you experience the rose as scarlet, ruby, or some other variety of red.

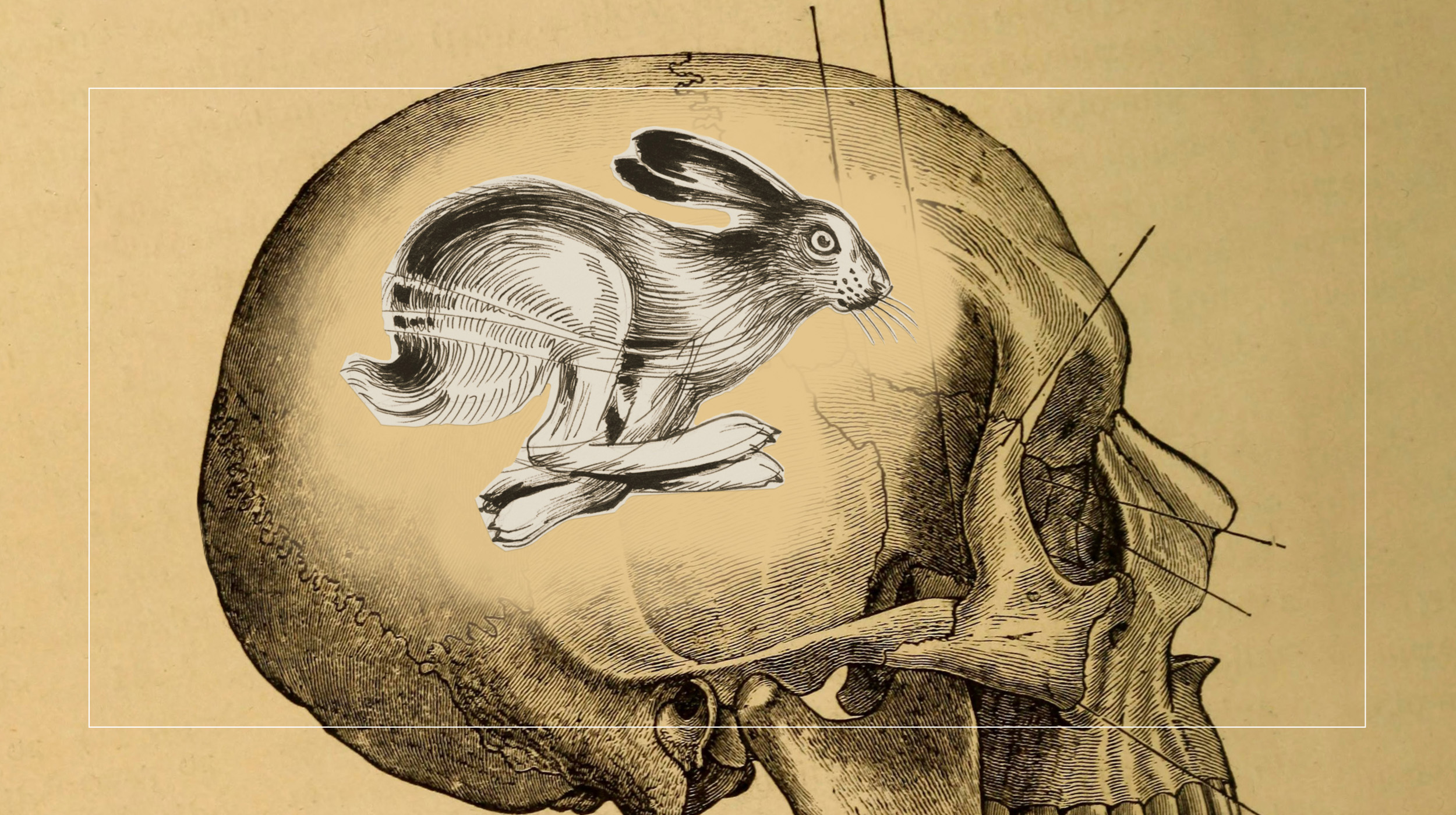

The model inside your brain

Your brain constantly runs a model of your body as it moves through the world. You come to know that world only through your cochlea, retina, and the other sensory surfaces of your body. Their signals, along with those streaming from within your body, continuously confirm or correct the ongoing signals in your brain. The implication is a bit startling: You cannot experience the world, or even your own body, objectively. Your experience is always from a particular perspective, and no perspective is universal.

Your brain’s internal model is formed from ensembles of sensory signals from your past, sourced from the body it is attached to, the world that surrounded it, and the other people who curated and inhabited that world. Their words and actions wired your brain with the concepts of your culture, empowering your brain to see red in a rose, hear trees fall, and understand your racing heart as joy in one situation and sorrow in another.

This idea, called relational meaning, is familiar in quantum physics. As Carlo Rovelli beautifully explains in his latest book Helgoland, nature is not filled with permanent objects but with relations between quantities. When an electron is not interacting with anything, it has no physical properties. An electron only has a position or velocity relative to something else. The same is true for signals that arrive at the sensory surfaces of your body, whether the signals originate within your body or outside it. They become psychologically meaningful only in relation to the electrical and chemical activity in your brain — a brain that continually creates a culturally-infused internal model of your body as it moves through the world.

Some experiences, like imagining the future and reliving events from the past, are constructed completely by the signals within your brain. Even some sensations are entirely your brain’s constructions. An example is the feeling of wetness. Your skin has no sensors for moisture, so how is it that you feel wet when you take a swim or get caught in the rain? Your brain constructs this sensation by combining physical signals from sensory surfaces for temperature and touch, and entwining them with other signals that reassemble your knowledge of what wetness feels like.

Your brain creates meaning

Everything you see, hear, smell, or taste; every touch you feel; and every action you take arises from a complex web of interwoven signals, and some of the most important signals are found only in your brain. Your brain does not detect features in the world and body; it constructs features to create meaning. Some constructed features are closer in detail to raw sensory data, such as lines and edges and color. Scientists call them physical features. Mental features are more abstract. When you appreciate a beautiful painting, the beauty is not in the painting; it’s created in your brain. When you eat a delicious dinner, the deliciousness is not in the meal but constructed in your head. The same goes for the last jerk who cut you off in traffic: You did not detect the driver’s jerkiness; your brain constructed it as an ensemble of signals.

Relational meaning also holds a key to understanding how emotions work. If you watch a World Chess match and see a player scowl, it may seem that you are detecting anger in their face, but really you are experiencing that chess player as angry. That experience is constructed in your brain by giving meaning to sensory signals that have no objective emotional meaning of their own. Pursed lips, flushing skin, and of course, a rapid heart rate are not inherently emotional. These physical signals take on emotional meaning only in relation to other signals, some of which are your past experiences that have been wired into your brain by other people in your culture. In this complex web of context, a grandmaster’s scowl might mean anger (about 30% of the time, studies show), but the same scowl can also mean that they are concentrating hard or even that they have bad gas.

If you find some of these ideas unintuitive, I’m right there with you. Relational meaning — the idea that your experience of the world says as much about you as it does about the world — is not “extreme relativism.” It is a realism that differs from the usual dichotomy drawn between materialism (reality exists in the world and you are just a spectator) and idealism (reality exists only in your head). It is an acknowledgment that the reality you inhabit is partly created by you. You are an architect of your own experience. Meaning is not infinitely malleable, but it’s much more malleable than people may think.

Changing your brain’s model

So, what does all this mean for everyday life? If physical signals from your body and the world only become meaningful to you in relation to signals created in your brain, this means you have a bit more responsibility than you might realize for how you experience and act in the world. For the most part, meaning-making is automatic and outside your awareness. When you were a child, other people curated the environment that wired experiences into your brain, seeding your brain’s internal model. You’re not responsible for this early wiring or the meanings it engenders, of course, but as an adult, you have the capacity to challenge those meanings and even change them. That is because your brain is always tweaking its internal model, creating the opportunity for new meanings with every new ensemble of signals it encounters.

To influence your internal model, you can effortfully seek out new meanings. You can expose yourself to people who think and act differently than you do, even if it’s uncomfortable (and it will be). The new experiences that you cultivate will manifest as signals in your brain and become raw material for your future experiences. In this way, you have some choice in how your brain gives meaning to a racing heart, whether it’s a chess champion’s or your own.

You don’t have unlimited choice in this regard, but everyone has a bit more choice than they might realize. By embracing this responsibility, you grant yourself more agency in how you automatically make meaning — and therefore over your reality and your life.