4 bizarre philosophical ideas that will warp your worldview

- Many people take common-sense views of the world for granted.

- Philosophy offers us other interpretations of reality, some of which are far more bizarre.

- These four ideas differ from how most people view the world in fascinating ways.

Philosophy underpins all areas of human thought. But for better or worse, most people are content to ignore the radical fringes of philosophy, or philosophy altogether, and instead embrace more “common sense” understandings of the world.

But sometimes the ideas philosophers introduce are truly shocking and suggest that the Universe we inhabit is nothing like what most of us presume it to be. Here, we look at four understandings of the Universe that are bizarre enough to turn the way you look at the world upside down.

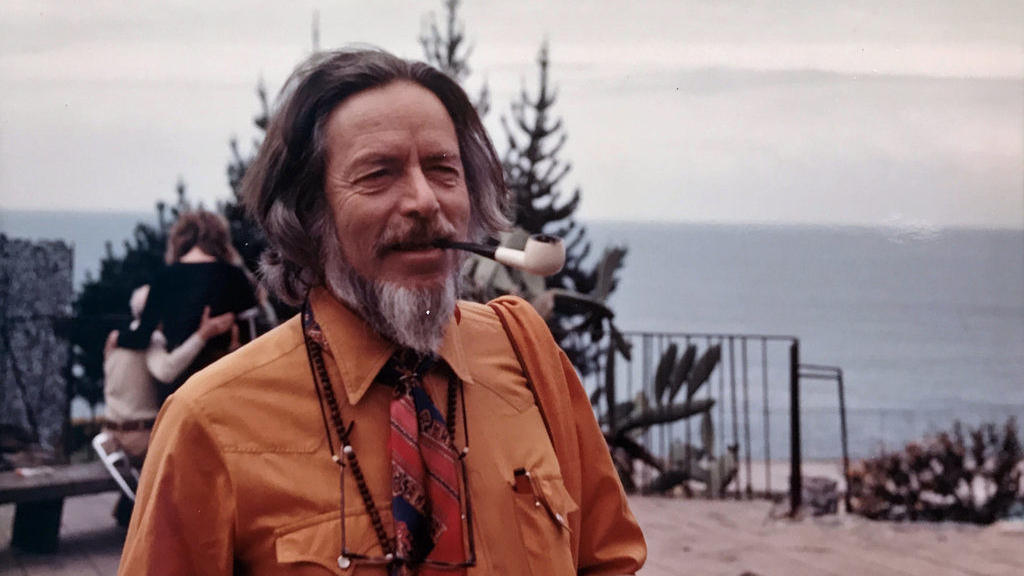

Kant: Space and time might just be in your head

Metaphysics — the part of philosophy that explores the nature of reality — can be hard to understand. It focuses on major questions such as:

- What exists?

- What does identity mean?

- How do cause and effect work?

- What are space and time?

That last problem was addressed boldly by Immanuel Kant, perhaps the most important philosopher of the modern age. Despite the occasional terrible idea, his thought has impacted nearly every field of human endeavor. He had a particularly large impact on how we understand our own understanding of the world around us.

Kant argued that while we collect much of the information we use from our senses, we can’t learn certain things from them. In fact, it almost seems like we need certain concepts, like causality, space, and time, in the first place so that what our senses tell us is organized in an understandable manner. He argues that your mind presumes that space and time exist — even if they do not exist outside your mind — so that you can comprehend everything else.

For example, try to imagine something existing without space. Kant says you can’t. You can imagine empty space or things in space. But things not in space? That defies how our minds work. The same, he says, goes for time. This view does not prove that space and time do not exist, but Kant argues we can’t know about the world beyond our experience.

If he is right, the ideas of space and time that so dominate the world you interact with might be constructs that allow you to interact with a world you never really see. The world as it is, unfiltered by your experience, may be completely beyond your grasp and understanding.

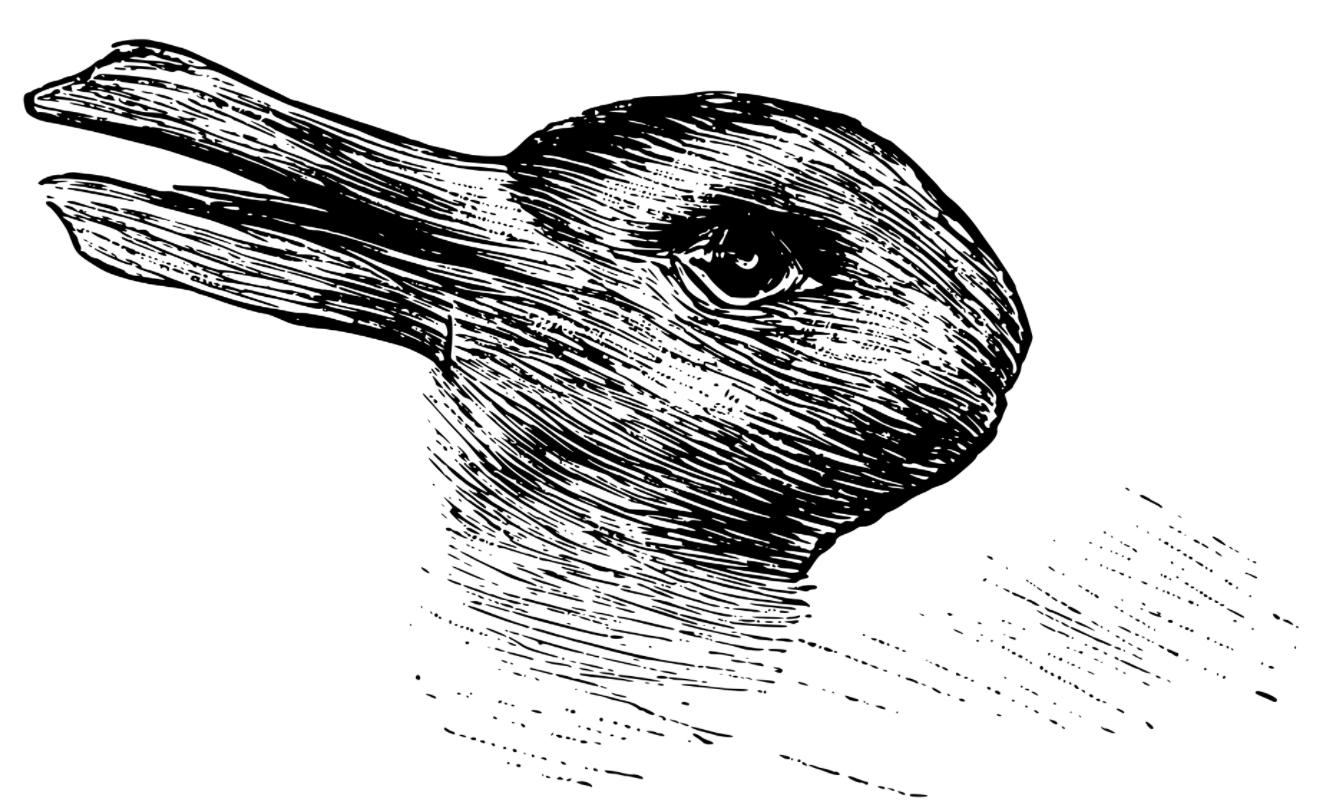

Idealism: Reality is made up of ideas, not matter

In daily conversation, an idealist is an optimist. In philosophy, an idealist is usually somebody arguing that the foundation of reality, or even the entirety of reality, is mental rather than physical. This idea isn’t new; variations of it predate Socrates, but ever-evolving versions of it provide a perspective on the world that is radically different from how most people imagine it to be, sometimes literally.

Plato’s theory of the forms, which argues that the world we interact with is a kind of imperfect copy of the “real” world of the perfect, unchanging forms, is a famous example of idealism- the “real” world is not the physical thing we engage with. George Berkeley denied the existence of material substance entirely, arguing that only minds and the ideas in them exist at all. Even Kant above, in his own way, is a kind of idealist. He argues we can only engage with the world as our minds filter it — not with the material.

A rather bizarre version of reality is to be found in some interpretations of Hegel, who developed a theory known as absolute idealism. While not the only take, it is possible to see his ideas as implying that everything in the universe, including humans, is part of God. When we do things like art or philosophy, the universe is trying to comprehend itself through ideas.

So, if some variation of this point of view is correct, then there might not be a material world at all. Or, even if there is, you might never interact with it. Instead, you are only engaging with your ideas of how the world really is- forever separated from it by a veil.

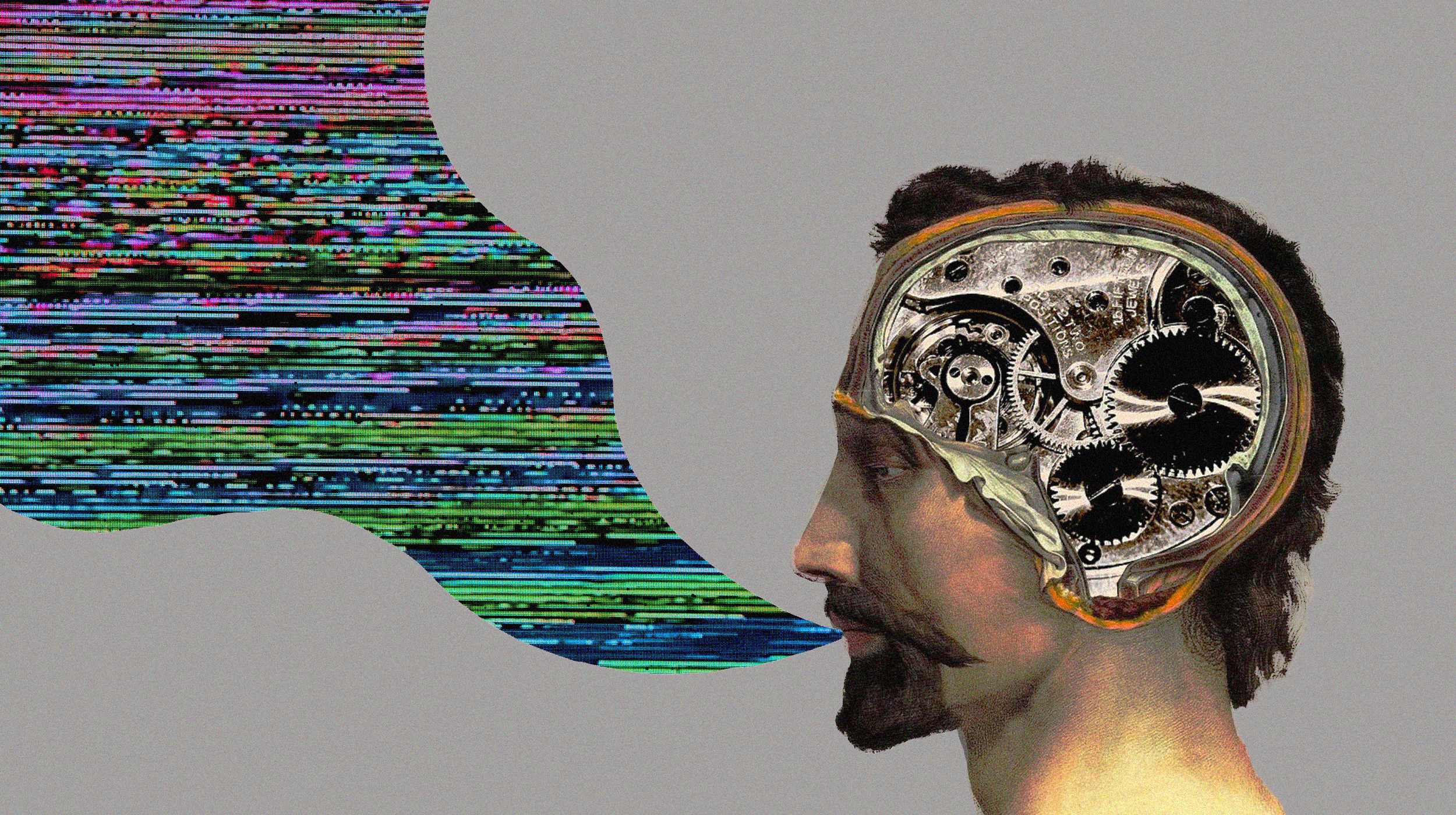

Eternalism: Everything happens everywhere, all at once

Time certainly seems to be straightforward in that no matter how much you might want to slow it down or reverse it; it moves towards the future and away from the past. It does this at a constant rate, barring relativistic effects, and appears to do so at regular intervals of itself. The future isn’t real yet. The past is real, but gone. The present is.

However, other views of time also exist. Eternalism is the view that all moments in time, past, present, and future, are all equally real. In one interpretation of this view, the universe could be considered a giant block, with different points having different coordinates in space and time. We can only view thin sections of time at once and always move toward the part with more entropy in it. However, that doesn’t mean everyone is at the same point in time simultaneously. Aristotle is just as present in ancient Greece as you are now in the present time.

If this is correct, then every moment of time already exists. “Now” is just a way of saying “here” for temporal locations rather than physical ones. The idea of moving through time is just an illusion as our perspective changes. Of course, “change” is a strong word for what happens. It is also probable that change is impossible if this theory is true.

Philosophical Skepticism: Maybe you can’t know anything

Most people understand the common meaning of the word “skeptic.” However, in philosophy, the term has a more profound meaning. It isn’t a question of if you believe that a specific source of information is trustworthy, but a broader question about knowledge. Can you really know anything?

Philosophical Skeptics argue that you can’t know much. Some arguments focus on more specific things. For example, Bertrand Russell pointed out you can’t prove the world wasn’t created five minutes ago complete with false memories and evidence of an older world. He didn’t argue that it was created so recently, only that this scenario was logically possible.

Beyond this are arguments against the idea of having knowledge at all. For example, the Münchhausen trilemma is a thought experiment that argues that all knowledge is either based on unproven assertions — proofs that require an endless series of prior proofs — or circular arguments, which assume they are correct in the first place. While the author of the problem, philosopher Han Albert, argued that this did not mean we couldn’t approach truth, he did argue that it removed the possibility of certainty.

While the most extreme Skepticism is self-defeating, more common forms raise important questions — unless, of course, you dreamed of reading this whole thing, which Zhuangzi and Descartes would both argue is possible.