Philosopher tells us why the elderly owe the young compensation for the COVID lockdowns

- Kal Kalewold, in a recent paper, argues that COVID lockdowns disproportionately impacted younger generations, leading to a moral and ethical question of whether the elderly owe compensation to the young.

- In an exclusive interview with Big Think, Kalewold delves into the intricacies of his argument, including ethical principles, historical precedents, and practical considerations for intergenerational compensation.

- While the argument attemps to resolve many possible objections, there are still certain unanswered questions.

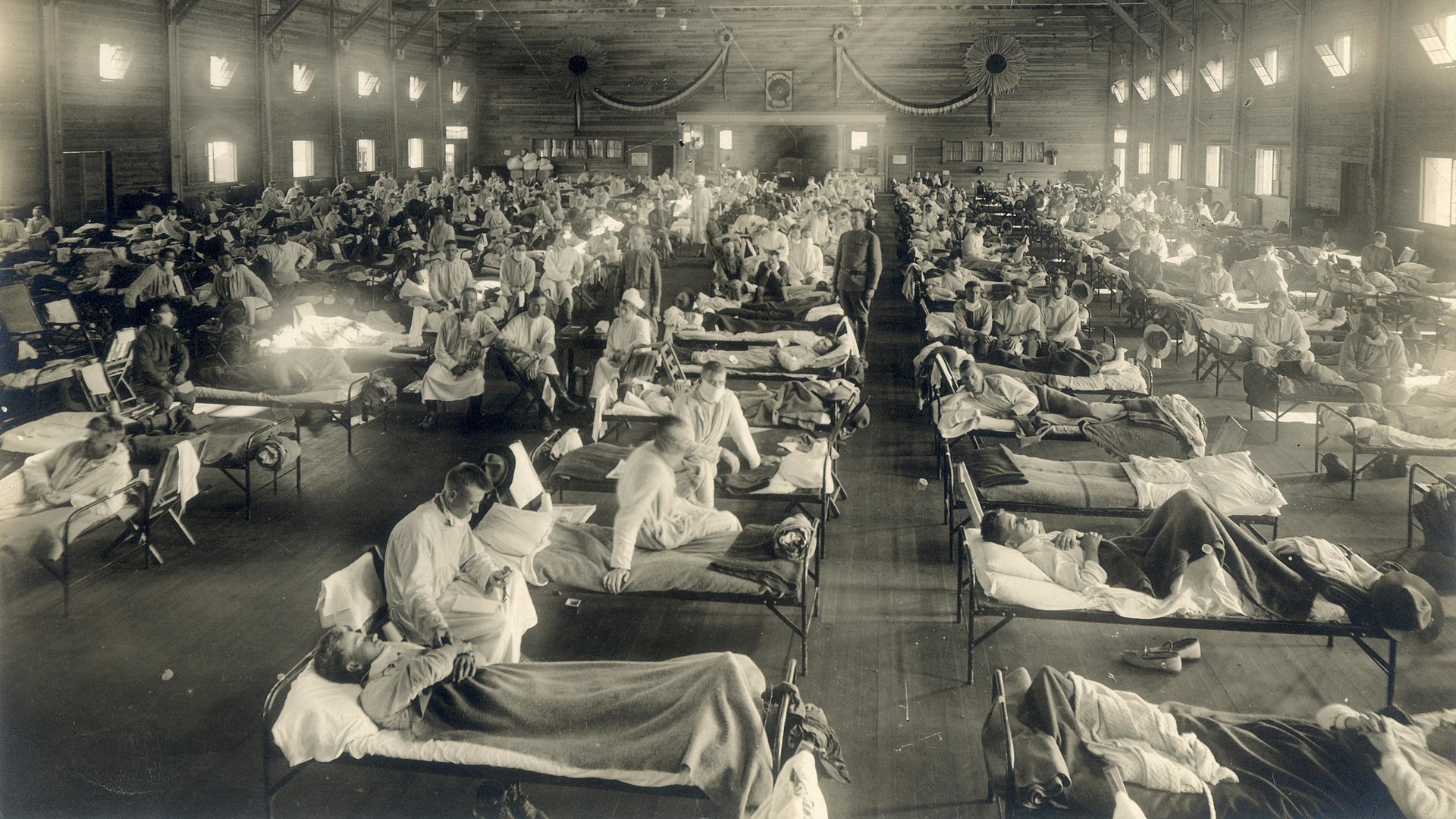

There has never been such a widespread and stringent lockdown as the one for COVID. There was some kind of social distancing for the Spanish Flu after World War I and localized lockdowns during Ebola outbreaks in West Africa, but there is no recorded precedent for the majority of the world following quarantine policies. Before the vaccination rollout, COVID was estimated to kill roughly 1.4% of those infected, with the immunocompromised and elderly at far greater risk. This means that the vast majority of people in the world went into lockdown to help protect a minority of their societies.

Lockdown harmed a lot of people in a lot of ways. Everyone felt the brunt of its isolation. But not everyone was harmed to the same degree. Hundreds of millions of students fell behind in school — and many remain behind. In a recent paper published in Politics, Philosophy, and Economics, the philosopher Kal Kalewold argues that the lockdown disproportionately impacted younger age groups.

This led Kalewold to ask a controversial question: Given the young were least at risk from COVID but likeliest to suffer from the effects of the lockdown, do the elderly owe the young compensation? Kalewold elaborated on his position to Big Think.

Intergenerational compensation

Kalewold presents an argument that the elderly do owe the young some form of compensation. His logic is as follows:

States were morally justified in imposing lockdowns. As Kalewold told Big Think, “Lockdowns were a medically and morally appropriate anti-contagion policy, given the nature of the sort of epidemiological threat COVID-19 posed.” Policymakers must consider the costs and benefits of laws, and the lockdown’s benefits outweighed the costs.

Lockdown policies shifted the burden of harm and loss due to COVID from the elderly to the young. In other words, a non-lockdown world would have harmed the elderly disproportionately. Lockdown, though, transferred the harm to the young.

How so? As Kalewold put it, “The nature of school closures, not just in educational attainment but in socialization, the displacement to industries like leisure, hospitality, and retail — these disproportionately impact younger age groups… There was a certain kind of double disadvantage, right? The young must first bear the costs of it and also then pay for the cleanup.”

Kalewold does not deny the elderly were also harmed by the lockdown; they were isolated and lived in an enhanced state of fear of the disease. But these were lesser harms than the young endured.

If harm is shifted from A to B, then A has a duty to compensate B. In ethics and law, there is an expression called “moral remainder.” This is where, if you harm or take something from someone, there is an imbalance that needs restitution. If I take coffee from the office kitchen, I need to put some back. If I harm you, I need to compensate for that. In this case, when the young sacrificed themselves for the elderly, even if done voluntarily, it resulted in a moral remainder. As Kalewold put it, “Just because a cost is permissibly imposed doesn’t mean that there is no duty to compensate.”

Therefore, the elderly have a duty to compensate the young.

Precedent and practicalities

Kalewold’s argument is compelling. It’s hard exactly to see which premise is wrong, and the conclusion certainly follows from the premises. The question of compensation and “moral remainders” is perhaps up for the most scrutiny, but Kalewold’s case is certainly sensible. The biggest issue with the argument is more practical than philosophical. Here, we might raise three questions.

First, is there any precedent for compensation of this sort? Kalewold told Big Think that COVID was a “one-off shock,” and that even faced with the likelihood of a future epidemic, “It won’t have the same epidemiological characteristics that COVID has. Maybe it will be one that severely harms children and young adults as the Spanish Flu did.” How, then, are we to find historical precedent for what he is suggesting? While there are cases of compensation for layoffs and displaced workers following trade deals, Kalewold says, “A really successful case of this being done is the American GI bill.” This was compensation that acted “as a kind of expression of gratitude for the millions and millions of returning soldiers who bore this extraordinary burden, even though it was their duty to bear the burden.” Something like this has been done before.

Second, how would a government enact such a compensatory policy? After all, “the young” are not a homogenous blob, and “the elderly” in most countries are not sitting on mountains of gold to be taxed. Kalewold suggests: “I think a wealth tax and a progressive intergenerational transfer. We would want to draw mostly from the elderly rich, right? Not just the elderly, not people who are surviving on state pensions or something like that, but those who hold a substantial stock of wealth.”

Finally, even if we agree to such a compensatory tax, how can we best “benefit the young”? The answer is to focus most on the areas hardest hit by the lockdown, such as education. It might mean getting rid of tuition fees or improving funding for higher education. Kalewold also suggests investing the money in future-centric policies such as “financing a better green transition” and “improving infrastructure that’ll benefit young workers.”

Residual problems

The argument is compelling, and while many issues are difficult, they are resolvable. This is not to say Kalewold’s argument will convince everyone. It could be that such generational taxes risk undermining social cohesion. Kalewold told us that he felt there was already certain intergenerational tension, and this policy could make it worse. What’s more, while the COVID lockdown was certainly a “one-off shock,” could it not be argued that previous generations (that is, today’s elderly) disproportionately endured hardships of their own in their youth, such as rationing and wartime bombing?

Even if we do not accept the idea of material compensation, the elderly probably do owe the young something — perhaps at the very least a sincere “thank you.”