I want to talk tonight a little bit about human disquietude. We are very peculiar creatures, because we have this urge to know and yet we’re also limited in our knowledge.

(Marcelo Gleiser’s blog post this week is adapted from his Templeton Prize acceptance speech on May 29, 2019. Watch his entire speech in the video attached at bottom.)

In 1686, the French philosopher Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle published a book about a conversation on the plurality of worlds, meaning other planets out there and the possibility of life in other places. (By the way, this is also the year that Newton published his book on the laws of motion and gravitation.) Fontenelle’s book was very interesting because it had two characters only; it was a conversation between a philosopher and a marquise, a very rare if nonexistent practice at the time, to have a woman as a protagonist. And furthermore, she was smarter than the philosopher, always asking very difficult questions.

One of the questions that she asked was, “Why do you do what you do? What is philosophy?” And the philosopher answered, “Well, you can summarize philosophy in two ways, it’s just a sum of two things. Philosophy is about curiosity and short-sightedness.”

I think that’s just beautiful because it encapsulates the whole idea that we, as humans, want to always know more, and know more about ourselves, about our lives, about nature, about the world, and yet we can’t. Of course, we progress, we move forward as we develop knowledge. But there is always a limit, a limitation of what we can see. That’s the short-sightedness.

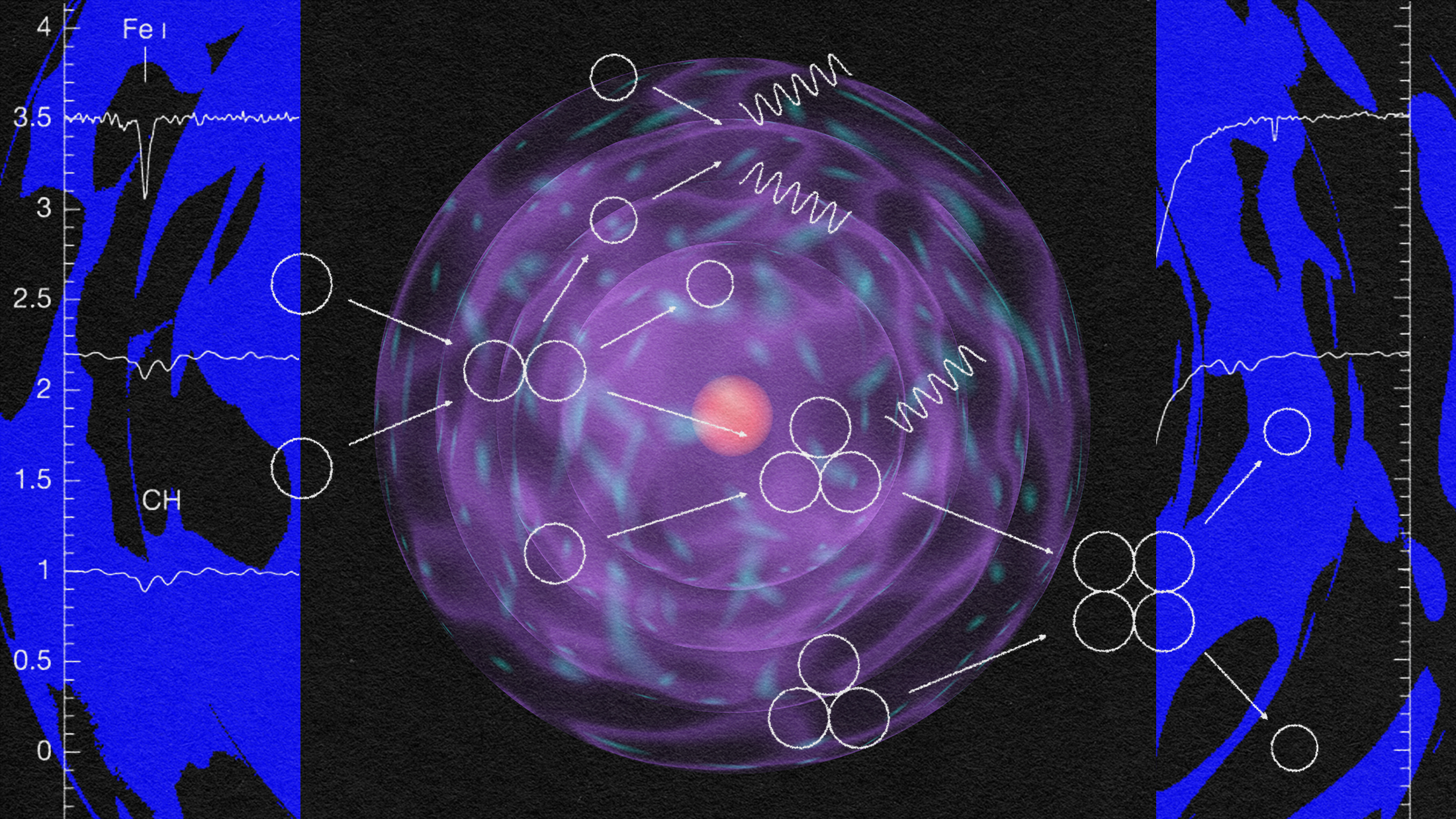

So what we do is something quite wonderful: we create instruments—I call them “reality amplifiers”—that will allow us to see farther into the reaches of reality that are hidden to us if we only use the five senses.

Because there is something quite amazing about what’s going on right now: There’s much that we don’t sense that is part of physical reality. For example, there are trillions of neutrinos coming all the way from the heart of the sun going through your body every second—and we have no idea this is happening. And we never would have known about neutrinos—or the heart of the sun, or how it shines, or how it creates the energy that makes life on this planet possible—if we had not developed scientific ways of thinking about the world: amplifiers, machines, instruments that allow us to see farther out.

We do this in a creative way, and we have done this for centuries. In fact, you can even tell the history of science and astronomy through the history of scientific instruments. In fact, tonight we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the confirmation of Einstein’s theory of general relativity, a feat that was made possible by developments in the precision of astronomical measurements, including star positions.

The ever-growing island

We have learned a lot and continue to learn a lot very quickly in many different fields. In my book The Island of Knowledge, I created a metaphor that I think speaks to the heart of how this works. The idea is simple. Imagine that everything we know about the world fits in an island, and this island grows as we learn more and more about the universe and about who we are. As with every good island, this one is surrounded by an ocean, the ocean of the unknown.

The paradox of knowledge is that as you learn more, as the island grows, the boundaries between what you know and what you don’t know are always growing. Which means that as you learn more, you’re able to ask questions that you couldn’t have even conceived of before.

Today, we talk about the digital era and information and data mining. Fifty years ago, this didn’t exist. Why did this happen? Because we developed knowledge to do that, that allowed us to reach out for more knowledge.

To me, this is an endless pursuit. And those people who believe that there is an end to science, an end to the way we can think about the world, and that we are going to go out there and conquer knowledge as if this were some kind of war—I think those people are deeply mistaken. Because one of the things we learn in the process of doing research is that we don’t know enough, and we’ll never know enough.

This is actually wonderful because it is the not-knowing that allows us to want to learn more. It is wanting to know that makes us matter, as Tom Stoppard once wrote. In the search, in this quest for knowledge, we find meaning. We understand better why we’re here.

And why are we here? We’re here to understand better who we are in this process called the pursuit of knowledge. In the last 15 years or so, we have been able to look indirectly at planets that go around other stars; not just our sun, but other stars far away. The more we learn about the universe, the more we learn about these other worlds, and the more we realize what a special planet Earth is. There might be other Earth-like planets out there: in our galaxy alone, there are about a trillion or more worlds, and so, statistically, some of them may look like Earth.

Why we matter

But Earth is special because it has all these special properties that allow for life to appear here about 3.5 billion years ago, and for that life to evolve in fits and starts, in complicated ways that could not have been predicted, in ways that if they had been changed, the course of life on this planet would have been different—and we wouldn’t be here.

So there is a contingency to the human condition which has to do with the way our planet evolved. And that is something quite beautiful, because it answers to what we call the “Copernican angst”—the notion that the more we know about the universe, the less important we become. This is what people think scientists are saying—that they are tearing down long-held notions that we were the center of everything and then we were pushed aside, and then we were just on a planet, and then the sun is not the center, and then we have a galaxy, and then there are hundreds of billions of other galaxies. It’s just one indignation after another: We keep being pushed out, and what is the point of all of these discoveries if they are telling us we don’t matter?

But that conclusion is wrong. Because it’s exactly when we look at other worlds that we understand how rare our planet is, and how rare life is. There is something very special about Earth, and about us, because we are the creatures that are able to understand, or try to understand, our origins. We are self-aware molecular machines capable of wonder and awe. And that, to me, is something that should be celebrated every day.

And more than that, in a day when Earth is being stressed by overpopulation and pollution and tornados, this is a moment for us to reflect on who we are—not as a tribe here against a tribe there, but as a species, one species unified on this special planet. We need to be together now more than ever, and to celebrate and respect life and one another.

And respect is not enough. We need to be open to learn from those who think differently from the way we think, because only then will we be able to go beyond these tribal divides—divides that were useful ten thousand years ago, but not anymore. We need to unite as a species so that we have a future.

For future generations, we must leave the world a better place than what we found. That, to me, is the moral imperative of our time. That is what I want to dedicate my next few years to, and the honor of having the Templeton Prize—to help create the sense of a moral imperative, where we humans work together to try to save this planet and life in it with everything we’ve got.

Watch the 2019 Templeton Prize Ceremony, including Gleiser’s speech, here:

The post Curiosity and Short-Sightedness appeared first on ORBITER.