To think like the philosopher Descartes, throw out all your beliefs and start over

- There’s much more to Descartes’ famous Cogito pronouncement, “I think, therefore I am,” than first meets the eye.

- For example, Descartes identified “I” with the soul, a substance separate from the body and all material things, and he believed that our existence continues after bodily death, unless God chooses to annihilate us.

- His work is seen as the foundation of modern philosophy, distinct in his approach from his predecessors, and is characterized by an attempt to start afresh in understanding humanity and the world.

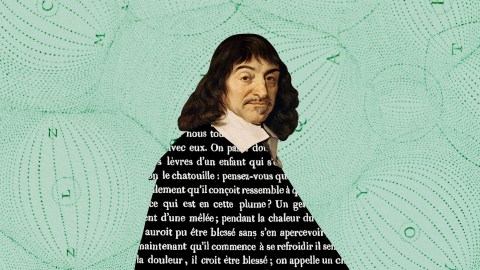

Where philosophy is concerned, anyone with a slight familiarity — even many with no familiarity — may find themselves occasionally announcing sagely, “I think, therefore I am”; they may even offer the Latin original as cogito ergo sum, even je pense, j’existe, muttering something about a French philosopher, Monsieur Descartes, and his famous “Cogito.”

By pure reasoning, Descartes drew fascinating, wide-ranging, and influential conclusions from that simple Cogito certainty, the most startling being that when we use the word “I” we refer to the soul; and the soul is the mind, is the self, is a substance totally distinct from the body and from all material things. Although we happen to be connected to our particular human body, with the luxuriant hair, fine physique, and coquettish smile or — all right, in my case — with the declining eyesight, greying beard, and sighs of weariness, we could exist disembodiedly.

Descartes does not stop there. Amazingly, from the Cogito, he also concludes that God, as traditionally understood, does exist; furthermore, each one of us will continue to exist after bodily death — though there is a caveat. I am a soul, a simple substance, without parts; so, I cannot be destroyed by being broken up as a wine glass could be smashed. The caveat is that God, all powerful, will annihilate me, if He chooses. Tread carefully, where God is concerned; that means, tread carefully everywhere and always.

Although many analytic philosophers find Descartes’ conclusion bizarre — they insist that he must have gone wrong in his reasoning — let us remember that millions, maybe billions, of people, probably many readers, embrace his conclusion, with varying degrees of certainty, be it by faith, scriptural commitment, or reasoning.

Descartes’ philosophy aims to create a well-ordered mind, a tranquillity, overcoming the mind’s illnesses. God is no deceiver, but we, mere human beings, are liable to make mistakes, become disturbed, unless we reason carefully and pay attention to what is possible. There are pleasures in contemplating the truth; there can be contentment, once we realize that we have a psychological freedom to overcome any distresses.

Descartes has become known as the Father of Modern Philosophy. Although writing in the 1600s, the “modern” indicates how different is his approach compared with the European philosophers before him. Descartes saw himself as starting afresh in understanding humanity and the world; and that meant not kowtowing to the Church or, indeed, to his schoolmasters’ teachings of pre-Christian philosophers, notably Aristotle. His Meditation I tells of how now he has sufficient maturity, leisure, and freedom from care to think clearly.

It is now some years since I detected how many were the false beliefs that I had from my earliest youth admitted as true, and how doubtful was everything I had since constructed on this basis; and from that time I was convinced that I must once and for all seriously undertake to rid myself of all the opinions which I had formerly accepted, and commence to build anew from the foundation, if I wanted to establish any firm and permanent structure in the sciences.

The mind lacks size or place in space, but essentially has thought. Things are the other way round for body.

Descartes’ work of meditations was distinctive not only in the seeming fresh start, but also in orientation as pretended autobiography. Readers were urged to follow in their own “first person” way and think through the matters with their own “fresh starts,” over months, rather than a quick read. To increase wider accessibility, going beyond that afforded to classical scholars, the text, originally in Latin, was soon translated into French. Descartes commented: “Common sense is the best distributed commodity in the world, for every man is convinced that he is well supplied with it.” Descartes displayed a sense of humor.

Descartes determined that he would doubt everything as far as he could. After all, he had often made mistakes, sometimes through poor eyesight, through dreaming, or tiredness. It was even possible — logically possible; no contradiction in the supposition — that a malignant demon, an evil genius, existed, deceiving him into thinking there was a world around him — a world of oceans and oysters, brains and biscuits — when in fact it was all illusion. Maybe the universe, including his body, his brain, was just treacle and he experienced a litany of false impressions courtesy of the evil genius.

The metaphor he deployed was that of a basket containing some good apples, but also some rotting ones. To avoid the rot spreading, it is wise to throw out all the apples and put back only the good ones. Similarly, in adopting his Method of Doubt, we should discard all those beliefs with even the slightest uncertainty and keep only those that are indubitably true. There are problems with the apple analogy; after all, we need some beliefs — perhaps they form the basket? — to assess other beliefs. A better analogy, put forward by Otto Neurath of the Vienna Circle, is: “We are like sailors who must rebuild their ship on the open sea, never able to dismantle it in dry-dock and reconstruct it there out of the best materials.” We have to rely on some of our beliefs to assess others, discarding some, retaining others — and then maybe reviewing those initially held firm.

Returning to Descartes’ approach, whatever the mistakes or deceptions encountered, realized Descartes, he would have to exist to undergo them. “I think — I am having experiences; I am perhaps being deceived — therefore I am.” In fact, it does not follow that Descartes could not doubt all that. After all, ply him with sufficient cognac and maybe he could doubt his existence. When we think of possibilities and impossibilities we have to be careful, and the care needs to extend to distinguishing between the psychological and the logical. We may make mistakes in believing something is impossible; we may also make mistakes in thinking something is possible, when logically it is not.

Descartes’ famous doubting with the “cogito” conclusion was not original. St Augustine, spanning the third and fourth centuries, had made similar observations — as some pointed out, to Descartes’ irritation. Descartes, though, used the Cogito to ground his insistence that the mind really is distinct from the body. The mind lacks size or place in space, but essentially has thought. Things are the other way round for body.