Why you should laugh at yourself, according to Seneca and Nietzsche

- Seneca and Friedrich Nietzsche had little in common in terms of their philosophical beliefs.

- However, both said that there is wisdom in learning to laugh at yourself and the problems that life throws your way.

- Nietzsche recognized, as Seneca did earlier, that if you’re overwhelmed by what you cannot change, you fail to act on the things that you can change. A lighter outlook might be the answer to dealing with fate.

We feel the nagging power of fate each day of our lives. Our umbrella is plucked before rain, an elevator door is shut in our face, we get stuck in bumper-to-bumper traffic, our flight is canceled. It’s human nature to feel upset and try to fight these things.

To the Stoic philosophers, however, being consumed by negative reactions doesn’t help you fix your problems or find peace. Sure, much of what happens in life is outside of our control. But we do control how we respond to the inconveniences and tragedies that fate tosses our way.

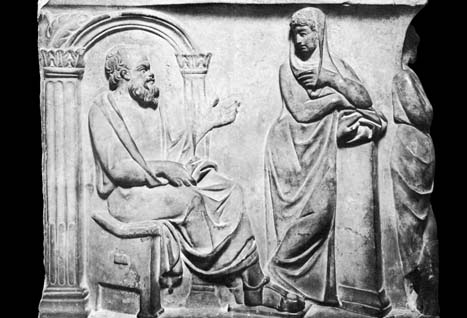

Seneca, a first-century Stoic philosopher and Roman statesman, argued that one of the best ways to react to your problems is to laugh at them:

“We should take a lighter view of things and bear them with an easy spirit, for it is more human to laugh at life than to lament it… one allows it a fair prospect of hope, while the other stupidly laments over things he cannot hope will be put right.”

To illustrate his point, picture yourself having a terrible day at work. You labor away, trying your best, but nothing seems to go in your favor. You feel more drained and frustrated by the hour, and you can’t wait for the day to be over. Then, as you walk home exasperated, a random bird flies by and, out of nowhere, splashes one on your head. And you freeze. It’s so unexpected that, at first, you’re shocked. But then, you begin to chuckle in disbelief. And you can’t help but burst into a defeated laughter:

“Laughter expresses the gentlest of our feelings, and reckons that nothing is great or serious or even wretched in all the trappings of our existence.”

Laughing — at yourself or your situation — shows a sudden, visceral understanding. You realize at last, with every inch of your giggling body, that nothing could have prevented that from happening. Yet you’re still okay. And your burst of genuine laughter releases a tension that was slowly building up throughout the day: your conflict with fate and acceptance.

As the Austrian psychiatrist and holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl put it in Man’s Search for Meaning: “To see things in a humorous light is some kind of a trick learned while mastering the art of living.”

Tranquility in the face of uncertainty

“What you are longing for is great and supreme and nearly divine – not to be shaken,” begins an essay by Seneca aptly titled “On Tranquility of Mind.” Seneca notes that finding inner peace is an inherent human goal, one that overarches histories, cultures, and social classes.

Seneca thought that few people are on the path to resilient peace and happiness. Most people are busy chasing empty pleasures, being troubled by restless desires, or fretting over their possessions. Why?

One reason is the failure to embrace a central tenet of the Stoic school of philosophy: the awareness that much of life is governed by fate and probabilities. The Stoics believed we should learn to accept and embrace this fact, instead of trying to fight what cannot be changed. Everyone, independent of their wealth, reputation, or abilities, is at the mercy of fate. And this uncertainty about life and death, or fortune and misfortune, is at the heart of what it’s like to be a human being.

Yet most people struggle when things don’t turn out how they want them to. They are frustrated, disappointed, and angry because they cannot accept the power of chance, something they clearly have no control over. And fighting against the unchangeable — like the past, an unlucky disease, being screwed by the weather, or other people’s decisions — is not only futile but exhausting.

This argument comes from the depths of Seneca’s personal experience. As a young lawyer preparing for public life in Rome, his life’s plan was derailed for a decade by an illness. Later, having amassed wealth and influence in the empire, power plays caught up to him: He was exiled twice before his own student, the notorious Roman emperor Nero, persecuted him and ordered him to commit suicide.

Despite his misfortune, Seneca seemed to have found plenty of room to maneuver in fate’s overbearing framework. He was an astute and content philosopher, but also a public figure active in politics. He espoused the uncertainty of his life and found tranquility in the one place he professed anyone could: within ourselves. To be happy, he said, we need to focus only on what is in our power: how we perceive the world and choose to act. In short, we must learn, in the face of misfortune, how to laugh.

Nietzsche agrees with a Stoic

What Seneca describes in On Tranquility of Mind is an undivided love for one’s life, in fortune and misfortune alike, to the extent that not even something tragic could threaten it. This is the most Stoic interpretation of amor fati, or loving one’s fate — a term attributed to the 19th-century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who wrote extensively about the value of laughter.

Although he disliked Seneca and most other Stoics for their grim, resigning view on life, the two seem to concur on the power of laughter to deal with hardship. In his magnum opus, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche alludes to the grave power of the devil to plant difficulties in people’s lives. It is by laughter, not hate, that the devil’s gravity can be quenched: “Not by wrath does one kill but by laughter. Come, let us kill the spirit of gravity!”

The same holds for taking agency in one’s life. Nietzsche discusses the majestic goal of living wholeheartedly, with courage and verve, as if living truly mattered. People must try to channel their inherent power to take risks and try, because even failing is better than not trying. And failures need not deter people from trying again, with the same joie de vivre, as Nietzsche wrote:

“You higher men here, haven’t all of you — failed? Be of good cheer, what does it matter! How much is still possible! Learn to laugh at yourselves as one must laugh!”

Nietzsche recognized, as Seneca did earlier, that if you’re overwhelmed by what you cannot change, you fail to act on the things that you can change — like pursuing a life you actually want to live. Fate has a tight grip on everyone, and life isn’t always fair or easy, but living it can still be wonderful. Instead of feeling defeated by adversity, you could welcome it confidently, smile and even laugh, and keep striving in its wake.

Fate and failure only hurt those who cannot come to terms with them.