Virginity vs. promiscuity: The philosophical problems with sex

- For much of Western philosophical history, sex has been viewed as a necessary evil to procreation, because it distracts us from more “worthy” things.

- Today, sex is often portrayed as just a pleasure to be enjoyed like any other — to have or not as you like. For the philosopher David Benatar, this raises a big problem.

- The problem of sex is that there are many different types of sex and society (as well as philosophy) is going through a recalibration period.

Thomas Aquinas is one of the most famous theologians and philosophers in history. His mammoth work, Summa Theologica, weighed in at nearly two million words and it came to define Christian theology and ethics.

Aquinas devoted an entire section of this book to the topic of virginity, arguing that it was even better than marriage and that celibacy was one of the greatest virtues. His Italian family, so desperate for little brother Thomas to have sex, devised a plan to lock the one-day saint in a tower with a prostitute. In an outraged reply, Aquinas lifted aloft a fire-lit torch and chased the woman around the room. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Aquinas died a virgin.

His thoughts on sex beg the question: Why has virginity, or chastity, been such a holy virtue? Conversely, why was sex viewed as bad, and can we find a philosophy of promiscuity?

Logos and eros

Sex is fun. A lot of people like sex. When you have an orgasm, you experience an intense rush of dopamine, oxytocin, and endorphins. Sex is often represented as the ultimate worldly pleasure. It’s a physiological explosion of gratification that overwhelms the mind with one simple idea and one idea alone: This is amazing. It pushes out all other thoughts and all other mental processes to focus on a delightful, carnal moment. In the sweaty, panting, passionate thrill of sex, humans are at their most animalistic. They abandon their higher faculties and revel in the base.

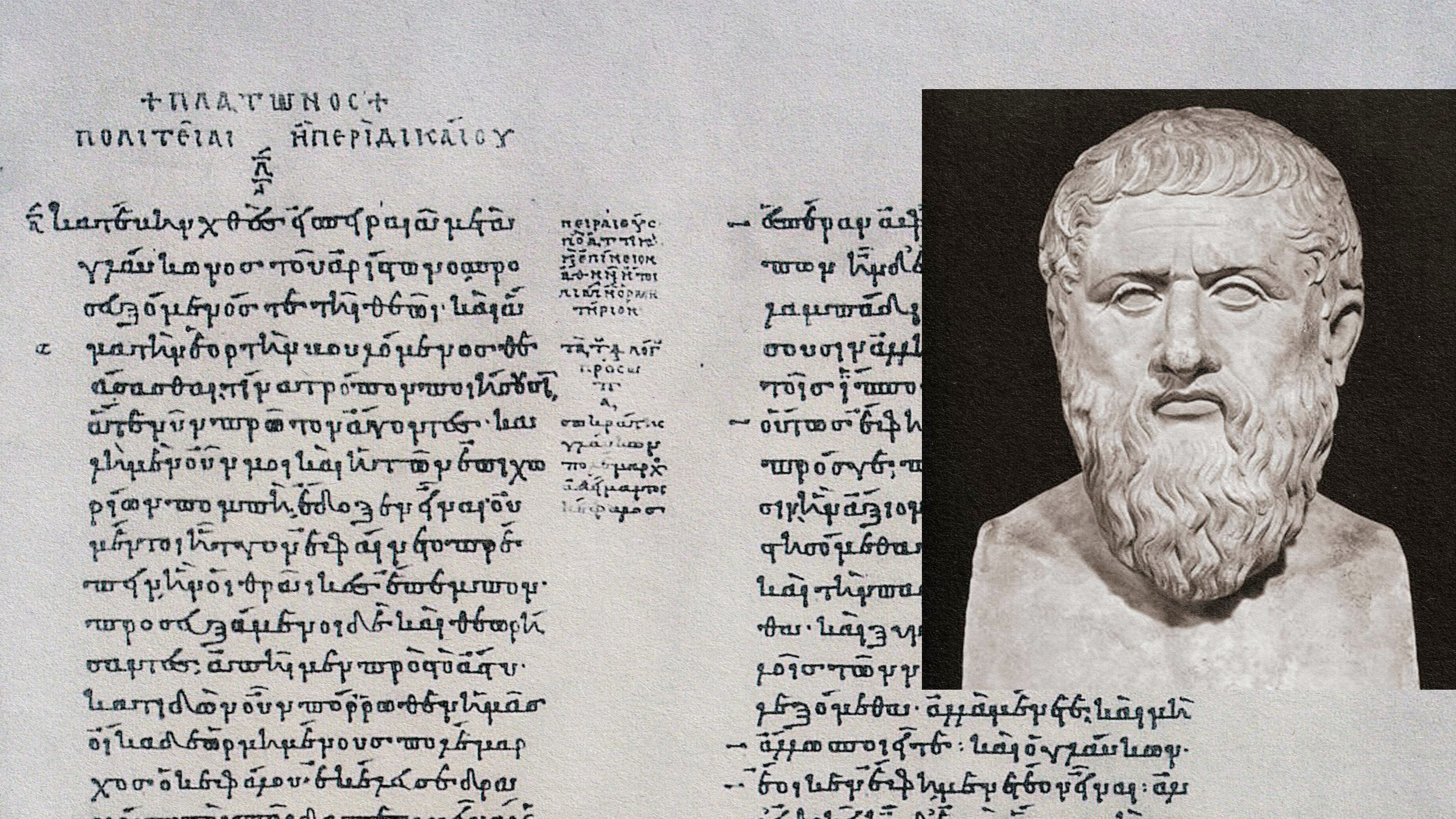

As the late Robin Williams put it, “See, the problem is that God gives men a brain and a penis, and only enough blood to run one at a time.” If you were a medieval, Christian saint-to-be, this poses a bit of a problem. The early Church fathers were the heirs of Plato, and, like the Platonists, they believed the physical world of sensation was to be spurned. Material concerns and earthly pleasures were distractions — little more than titillating baubles to tempt you from the path. But what path was that?

For Plato, it was logos, which is rational meditation. For the Christian Church, the mark of a good, virtuous life was contemplation and prayer. It was about faith. The problem? When you’re fornicating, you’re rarely thinking of God. As Aquinas puts it, “The end which renders virginity praiseworthy is that one may have leisure for Divine things.” In Question 152, titled “Virginity,” Aquinas compares virgins to martyrs. He observes that both groups surrender their bodies — and forego bodily pleasure — for the supreme goal of cleaving to God.

Sex is bad, then, because it reduces our higher faculties and indulges our animalistic impulses. The promiscuous person, for Aquinas, is bad not because sex is bad, but because it debases them.

Pleasure like no other

Today, our sexual laws and ethics are less defined by religious beliefs. We also are less likely to care for and lionize the “rational mind” as much as Plato or Aquinas did. In a post-war, post-modern world, reason has no privileged position over emotions, intuition, or other ways of knowing.

So, in the wake of the sexual revolution, sex experienced a rebranding. It was no longer about procreation, or about having (or needing) any romantic or loving significance, at all. From the 1960s onward, sex could be seen as a pleasure like no other, more analogous to a fine dining experience. Sex is enjoyable, no doubt, but it’s no more a “sin” than eating a steak or drinking an aged wine. As the philosopher David Benatar puts it, “condemning sexual promiscuity would be as ridiculous as condemning “‘casual gastronomy,’ ‘eating around,’ or ‘culinary promiscuity’.”

For Benatar, there is an inconsistency in logic here. He argues that if sex is a pleasure no different in kind to food or going to the theater, then why do we still view rape as such a terrible crime? Rape often gets similar prison sentences to murder. However, if we view sex like any other pleasure — like eating — why do we view it as such an evil? Benatar puts it like this, “Raping somebody for whom sex has as little significance … as eating a tomato, would be like forcing somebody to eat a tomato.”

Rape is evil. It’s justly seen as one of the worst crimes humans can commit. The fact that most societies see this as true is, for Benatar, a sign we view sex as more than “just another pleasure.”

The problems with sex

The question underpinning an acceptance of sexual promiscuity boils down to how significantly you classify the act of sex. We do not have to accept Aquinas’ position to appreciate Benatar’s: Sex is different from other pleasures like food or a movie.

There are two problems when we talk about sex and sexual ethics. The first is that there are many types of sex: Sometimes it’s for love, sometimes it’s for pleasure, and sometimes it can be deliberately (and unromantically) for procreation. Sometimes it’s all three. Other everyday pleasures are not so complex and so any attempt to philosophize about sex will first have to wade through a lot of categorical work.

The second problem is cultural. There is no uniform consensus about sex or sexual behavior. The glutton and hedonist are far more socially accepted than the slut or the libertine (not to mention how disproportionately negative these are for women compared to men). There is a far broader scale of acceptability when it comes to sex than almost any other type of pleasure.

The philosophy of sex is a new and unestablished discipline. As such, it’s going through a kind of recalibration period. For centuries, it was considered either a foregone conclusion or just plain uninteresting. Today, it’s neither. There are a lot of questions for philosophers to grapple with.