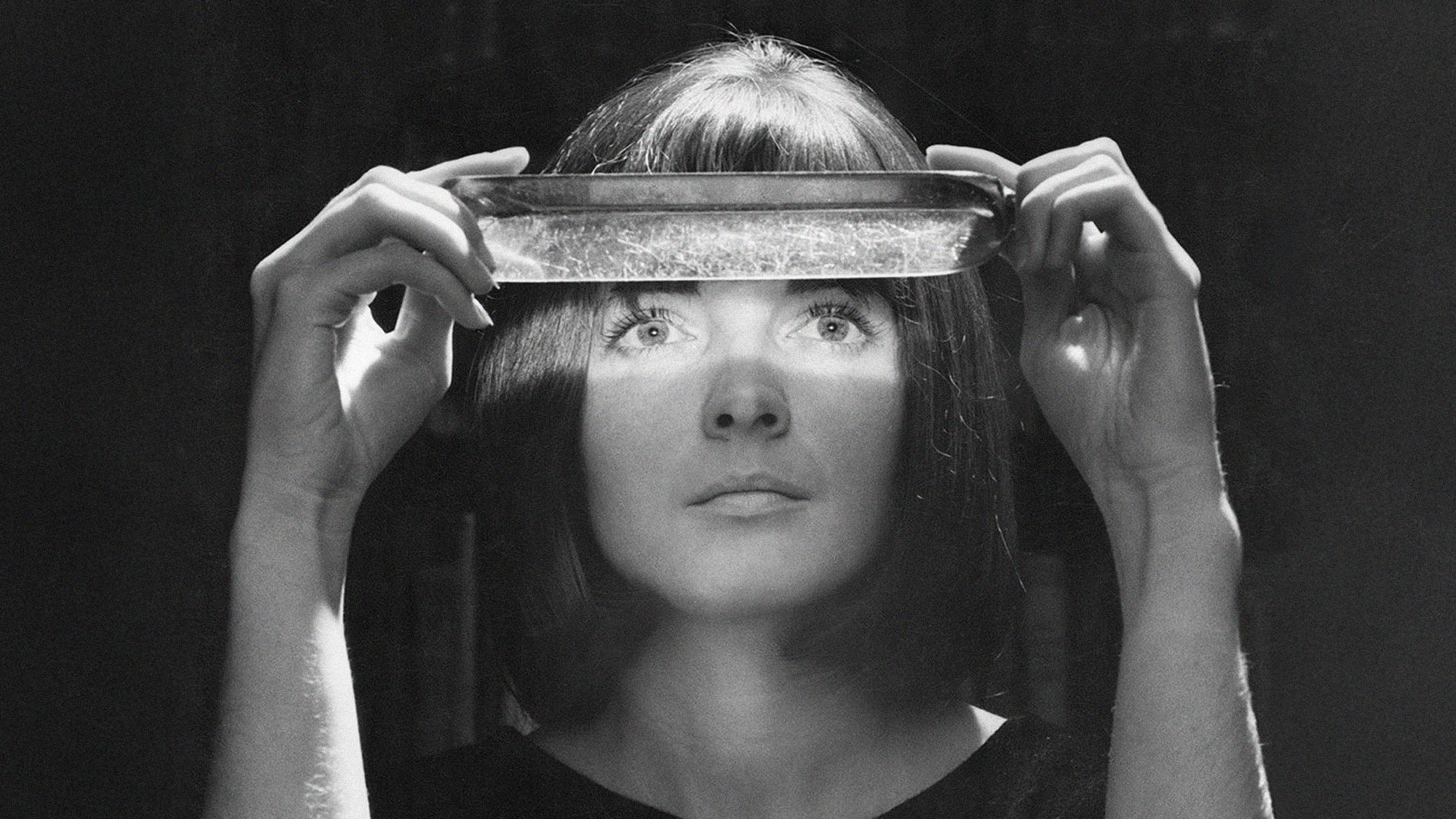

There are circumstances where violence is unavoidable, says author Andre Dubus III, but it always takes a heavy spiritual toll.

Andre Dubus III: You know, I think what enabled me to write the memoir was something that happens often in fiction. You know, when I look back at the fiction I’ve published and even the fiction I’ve finished but haven’t published . . . they’re really sort of the phoenixes that have risen from the ashes of what failed, which is pretty normal for, I think, a lot of people who write.

So for me, I was actually working on an essay about baseball. And, because here’s the deal: I didn’t know what baseball was until, really, my 40’s when my kids got into it. And my oldest son when he got into it, I noticed as he got older, the coaches became more competitive and I didn’t want my son to have a drill instructor coach at age eight so I volunteered to be a baseball coach, except I quickly realized I don’t know how to play baseball. So I’d go “Run, Tommy, run!” And some little kid would be pulling on my shoulder and say, “But coach, you can’t run.” And I’d say, “Oh, you can’t? Oh, I’m sorry.” So my point is, what was fueling the essay was the question, how did I miss baseball, this game that I really love now as a grownup? You know, what was I doing instead of playing ball?

And you know, I vaguely knew what I was doing. But 550 pages later, I wrote what I was really doing, which was living in poverty with our single mother and my three siblings and moving sometimes two to three times a year for cheaper rent, and, you know, getting beat up a lot and then snapping and learning to fight and then becoming a violent young man, until, thank God, I found writing, which kind of saved my life.

You know, I really wrestle with this whole notion of what a modern man is, and I find it an endlessly fascinating subject. I think you have to talk about this in a class way. You know, when I go back to the neighborhoods I grew up in and I go to the bars I used to hang out in 30 years ago, there are still guys there my age, in their early 50’s, who will get in a fight even though they could lose a house or get shot now. I’m not saying that working class people are more violent by nature; I think that educated, upper class people get taught early that that’s not the way to express yourself. And I think there are more options that keep you from expressing yourself that way.

I have to admit that as much as I hate violence, and as much – and hopefully Townies is about that, I have always hated violence, I was a sensitive kid who got beat on and I learned how to become a perpetrator, but I always, at a spiritual level, knew that what I was doing was negative. That said, I do believe that part of being a man is being able to defend your wife from an assault. And I think that most men would probably agree if pressed. And the truth is, I haven’t punched anyone in 25 years, but I still know how to do it and I’m glad I do. And I hope I never have to.

But that’s one of the things, you know, I write about in Townie is that I think the biggest thing I learned when I went from being a non-fighter to a fighter is not how to throw a punch – anyone can learn that on a heavy bag or with an instructor. The biggest learning was what you have to do to yourself spiritually and psychologically to hurt another human being. And that whole notion in the membrane, I describe, where – this was something I was semi-consciously aware of during my fighting years, but – it’s really inappropriate. . . . You know, we just met. It would be inappropriate for me to reach over and touch your cheek, even, you know, gently. It’s a violation of your private space. I don’t know you well enough; it’s inappropriate. Think how inappropriate it is to ball your fist up and punch someone in a face as hard as you possibly can. It is such a violation of sort of this membrane that’s around all of us that should be inviolate and sacred.

We should all have this barrier around us that no one can come into without our permission. When you look at consensual sex between adults, you know, we lower that barrier. We say, yes, you can come close. And that’s fine. But in a fight, you have to violate that barrier, and to me, that was the biggest piece of learning psychologically, is you have to learn to violate that. In order to violate, to break that membrane around somebody, you’ve got to break that membrane around yourself. And in my experience, I had to break and keep breaking and keep tearing my own compassion for another human being, my own sense of suffering with someone else, to really not care if I hurt that person I was punching in the face.

So, back to the dilemma of the modern man. I think the more educated and sensitive and empathetic we get is all good, but I frankly think we need to keep hold of that reptilian part of ourselves that is not reasonable and knows how to tear that membrane if we have to. And may we never have to.

And by the way, it’s harder to not fight than to fight. Once you know how to do that psychologically, again, it’s much more of a psychological stance in the world to be a fighter than a non-fighter. Once you’re in that zone it’s very difficult not to reach for the gun, the metaphorical gun, because it’s harder to be diplomatic and it’s harder to resolve conflict with speech. And it’s got me thinking about nuclear war and weapons. It’s easier to press a button than to engage in five years of messy diplomacy. And I just – my years as a fist fighter informs that thought.

Directed / Produced by

Jonathan Fowler & Elizabeth Rodd