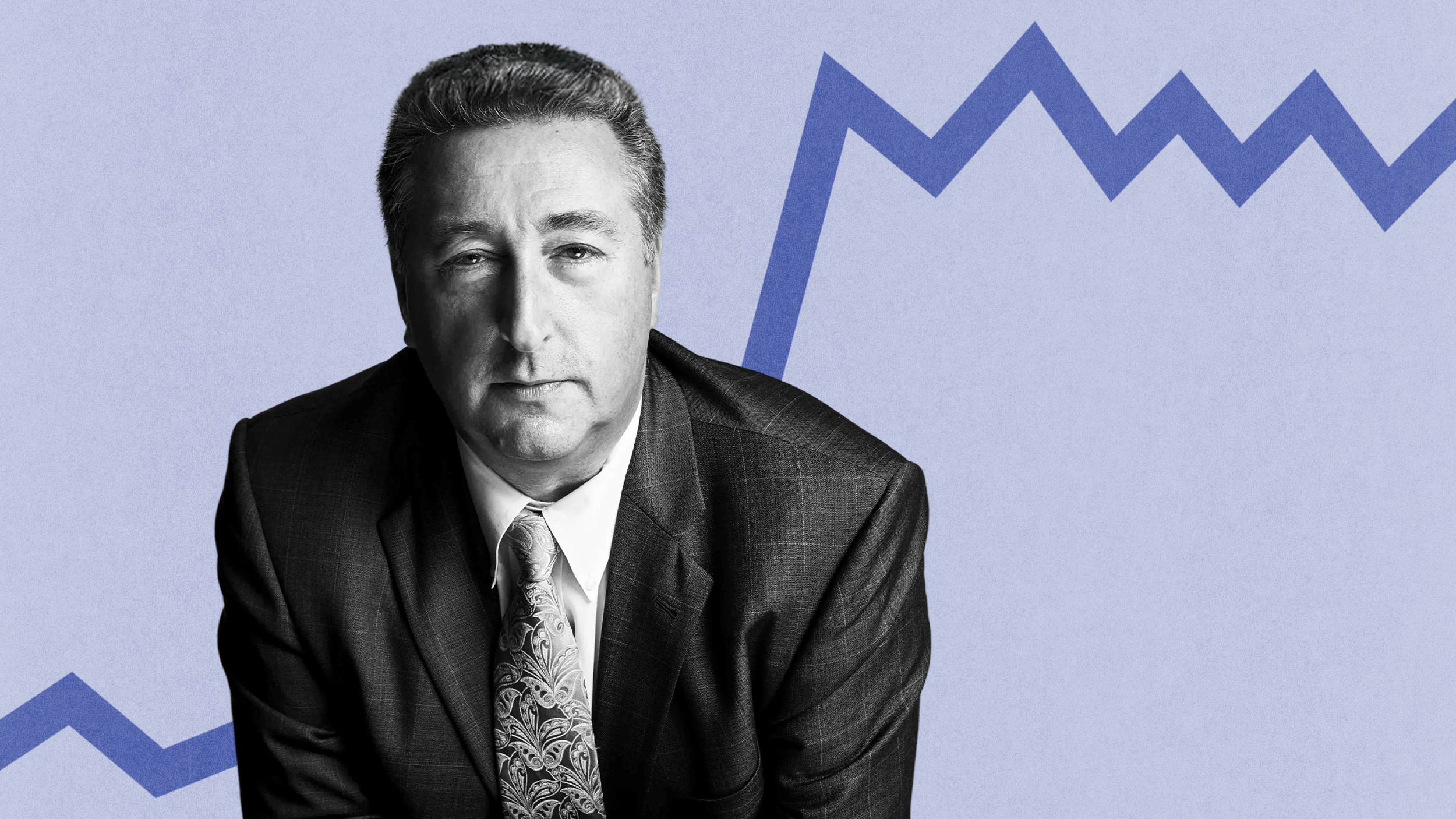

Barry Nalebuff on starting Honest Tea, a bottled organic tea company.

Question: How did game theory impact your decision to start Honest Tea?

Barry Nalebuff: I’m only sorry I don’t have any product to demonstrate here.

I would say it’s really more economics than game theory is the motivation. One of the first lessons we teach people in economics is the notion of declining margin utility, so a little bit of salt adds flavors. The next bit is not quite as much, and by the time you put too much salt in, you’ve ruined things.

First pair of shoes prevents your feet from getting cut. The second pair might be a pair of running shoes. By the time you’ve had thousand pairs of shoes, that next pair you don’t get to wear very often isn’t worth as much.

Well, maybe our example is a bad one for half of your audience, and the same thing is true with sugar.

And what was peculiar to me is that the beverages that are out there were either zero calories, so many calories they were liquid sugar or sweetened to the point with artificial. And, if I said to you, look, I want you to cook me dinner, but you are not allowed to use any calories, so I don’t know what you’ll give me? A leather belt. And I said, oh, guess what, you can now add some garlic, some onions, some lemon and maybe even ketchup. Wait, you know, for 20 calories, you can get a whole lot more flavor going on here.

And the notion that somehow you wouldn’t want to create a beverage that had 20 to 40 calories as being the sort of sensible [IB], the first little bits of sugar take away bitterness and add a little more flavor and then kind of stop. And I didn’t understand why those beverages didn’t exist in the world where people go to restaurant they tend to put zero, 1 or 2 teaspoons of sugar to their tea not 12.

And so with the former student, Seth Goldman, we created a company to create normal beverages and that’s what led to our Honest Tea.

Another insight was that the cost of ingredients is really the smallest part of what’s going on here. If I wanted to sell empty bottle of tea with a label and a cap and a glass bottle in the case, sent to the store through the distribution network, it will probably cost me $0.80 to get that bottle of air onto the shelf.

Now, if I put basically crap in there that many other people fill their bottles with, it’ll cost me under a penny, but I could put really good tea in there for $0.05. So between $0.80 and $0.84, so the extra $0.04 it’s not a big difference in terms of total cost, but we’re spending five times the amount on ingredients you care about, and it turns out you can taste the difference.

And so, people are often focused on the parts of the cost that they can control and that’s why they substitute high fructose corn syrup for sugar--because it’s cheaper. But the end, that’s a tiny fraction of the total cost customers are spending, and so, for really very little extra you can make the taste a whole lot better and customers seem to be going along that.

We’re the number one organic tea now in the United States and we’re growing it is just about 100% in February. Coca-Cola invested and bought 40% of the company. We’re continuing to control it and things are going well.

Question: How did you name your product?

Barry Nalebuff: I was in India writing a case study on Tata, the leading industrialist in India. One case study was on their car parts business, and one was an old business and just happened to be tea. I had no particular knowledge or interest in that.

As part of doing my research, I went to a tea auction, and I realized that I could tell the difference between great tea and bad tea. I couldn’t tell if I used wine as the example Kendall Jackson from Stags Leap, but I could tell the two of them from [Boone’s] Farm or [IB].

And I realized that we were drinking the equivalent of [IB] or worst, as opposed to the Kendall Jackson of tea. And even if I as a non-connoisseur could tell the difference, and the good tea was $0.05 rather $0.01, well, then this was a real opportunity to create a new type of beverage in the United States. Tea could be the next coffee, if you like, just like Starbucks did for coffee, we could do for tea.

Now it turned out that Tata was interested in exporting its tea outside of India, and nowadays a few people hearing of Tata. Now that Tata has bought Jaguar and Tata Consultants, but 10 years ago, not very many people knew of Tata outside of India. And so I thought that Tata needed to come up with a name to represent what it stood for rather than Tata. And so I thought, well, okay, it’s tea, this is reliable, it’s trustworthy. Ah! They should call themselves Honest Tea outside of India.

We went to trademark the name. It was blocked initially by Nestle because we had one [letter] "t" and so Honest Tea was Ho Nestea and we explain we won’t be [IB] the whole market. But in the end, we changed things to add an extra "T" and a space and so it became Honest Tea and that was really the better decision anyway because really were beyond tea.

We have kid’s beverages, we have Honest Bars and we were the Honest Food Company. And when it comes down to, when you sell a product that somebody puts in their body, trust is about the most important thing that you can offer, and we like to think that we are doing business in a way that people can trust where we up to and that’s resonating with customers.

Recorded on: Oct 2, 2008