Is internet access a human right? MIT’s Nicholas Negroponte thinks so. As education and the internet become further entwined, the need to connect more and more people will arise. In this interview, Negroponte explains how a geostationary satellite system could bring the internet to remotely located people in Africa.

Nicholas Negroponte: Education is a human right for sure. And Internet access is such a fundamental part of learning that by extension it is almost certainly a human right and within a very short period of time it will be particularly because of those who don’t have schools, those who have to do their learning on their own. And for them Internet access is access to other people. It’s not so much the knowledge. It’s not the Wikipedia but it’s the connection to others, particularly kids to other kids – peer to peer learning. So yes, Internet access will be a human right. At the moment it’s edging up to it and probably not everybody agrees but they will shortly.

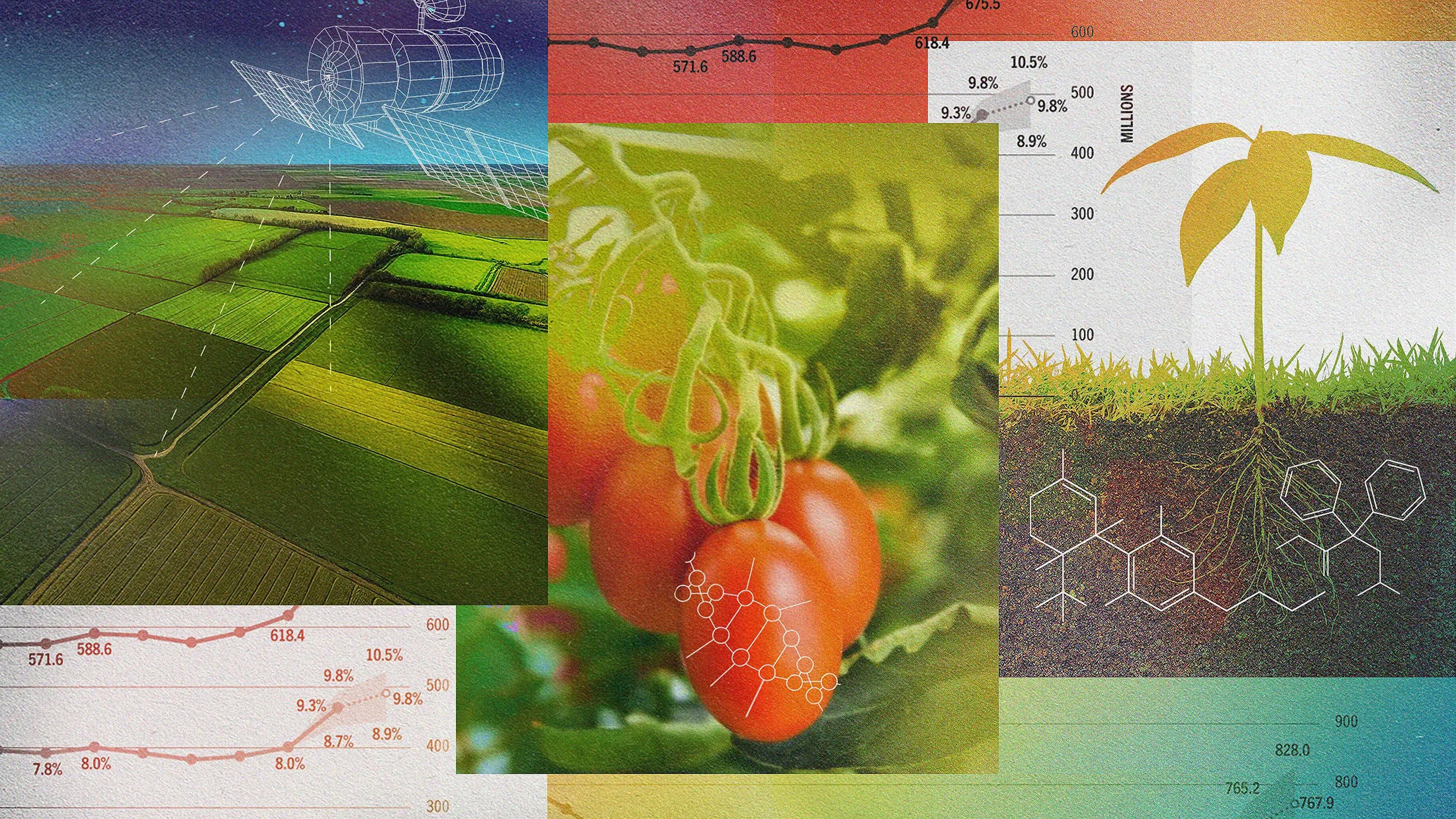

Because I believe the Internet is a human right we can look at the number of people on the Internet at the moment which is anywhere between two or three billion people depending how you count out of seven. And the next billion is a little bit like low hanging fruit. You can do some regulatory changes, you can do some subsidies, you can bring the next billion in quite easily. To me I’m much more interested in the last billion because the last billion people are a technology problem in many ways. They’re a cultural problem. They’re in low density areas, mostly rural. They’re just many challenges which make the two problems, the next billion and the last billion different problems. And I’m interested always in the harder problem and the one that maybe normal market forces won’t do. And so I have been involved in the past six, eight months in trying to bring the Internet to those last billion people. And because they are in low density rural areas, I focused on geostationary satellites not just because they have a big footprint but because they’re there.

And 50 percent of the bandwidth over Africa, for example, is not being used at the moment. So there’s a lot of unused capacity. You can move satellites quite easily and then you can launch a satellite. So there’s a pretty orderly schedule for how you would do this. And then the other thing which people forget is that the liability and the asset of geostationary satellites are the same. Namely you’re going up 22,500 miles and back down again it’s a pretty long roundtrip. The latency, the power, all of those issues. But Africa is the same as Europe as far as the satellite is concerned. So if the satellite’s positioned somewhere at an orbital slot over Africa on the equator it sort of looks down to the right and sees Africa and looks down to the left and sees Europe. So you can build a system that serves Africa by landing in Europe because one of the reasons you don’t want to land in Africa is that the sort of backbone of the Internet in Africa’s quite costly. And landing in Europe is not very costly. So you could have what’s called, you know, a farm of dishes in some location in Europe that serves Africa. Not the long term solution but a very quick short term solution. And I believe that one should be doing these things now with resolve. There’s no technical holdback. It’s just a couple of billion dollars to do it and that’s what we spend in Afghanistan in one week. So this isn’t off the charts.

Directed/Produced by Jonathan Fowler, Elizabeth Rodd, and Dillon Fitton