Be thankful for cosmic beauty

- There are many good reasons to do science. Appreciating beauty is one of them.

- Everyone should pause to gaze upon the awe-inspiring Butterfly Nebula.

- Appreciating cosmic beauty helps us realize that we are all connected.

There are a lot of reasons to do science. The ability to produce techniques and technologies that can help people is one good motivation for doing the hard work of research. Unveiling the fundamental nature of reality is another. But what about the pursuit of pure beauty? Is that a good enough reason to spend untold hours hovering over a telescope, a microscope, or a computer? Is the pure experience of aesthetic pleasure — the same kind of thing you would get from making or viewing art — a good reason to do science?

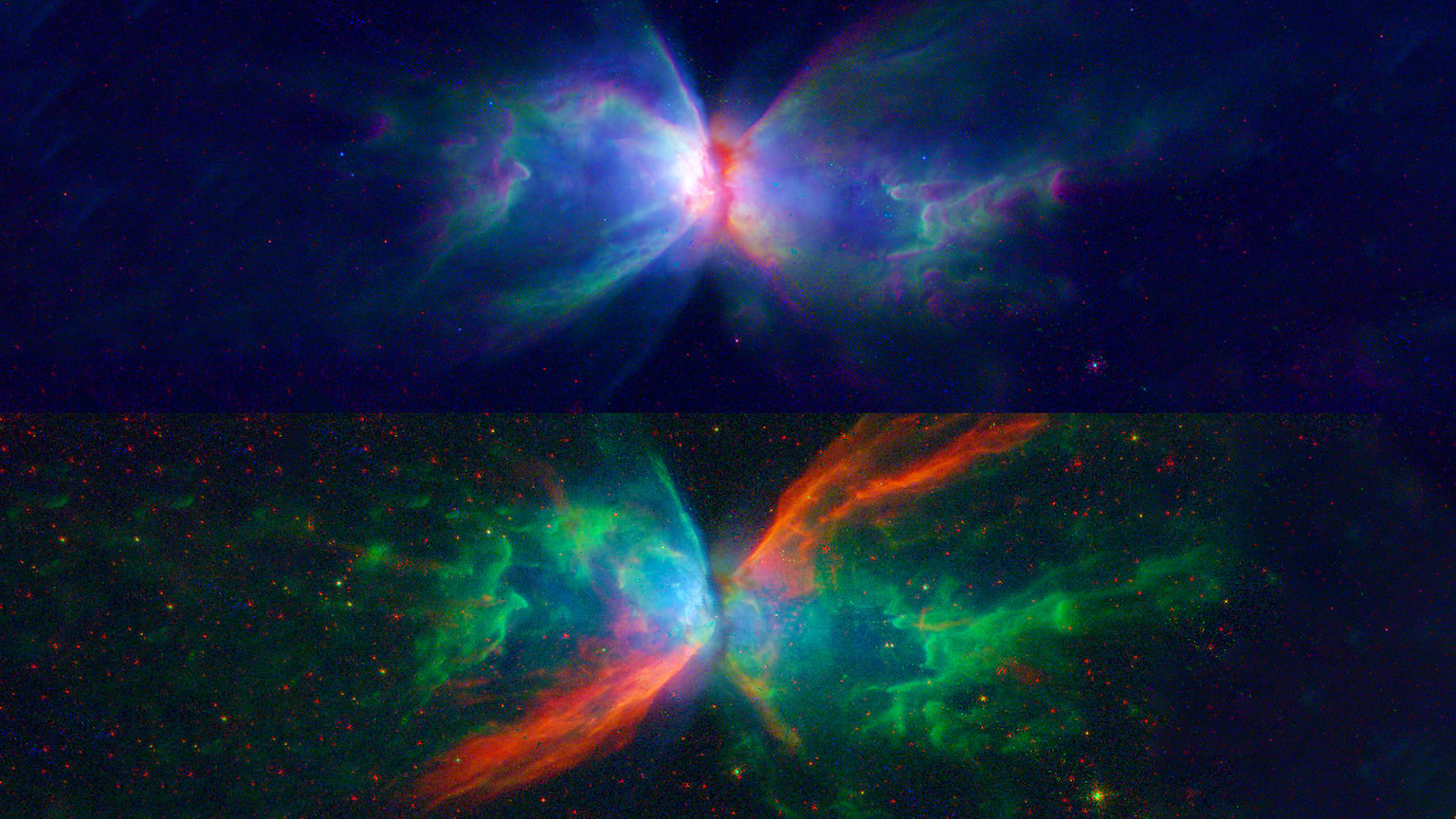

This question has been on mind as I contemplate the remarkable, breathtakingly beautiful image of the Butterfly Nebula.

The pictures above are of NGC 6302, which is an example of what astronomers call a planetary nebula. What we are seeing when we view a planetary nebula (“PN”) is the penultimate stage of evolution for stars like the Sun when they shed much of their mass into space via powerful winds. (They have nothing to do with planets; it’s an old term that just stuck).

My colleagues Joel Kastner of the Rochester Institute of Technology and Bruce Balick of the University of Washington (along with others) were awarded observing time with the Hubble Space Telescope to take new images of NGC 6302. Because earlier images already showed that it exhibited remarkable “bipolar lobes,” they knew this PN probably originated from a binary star. When two stars orbit each other closely, their motions can shape stellar winds that originate from either of the stars. Stellar material gets violently ejected along the direction perpendicular to the orbital plane, leading to the remarkable butterfly-shaped lobes.

By taking images in different wavelengths of light, Kastner, Balick, and the team (of which I am a part) could highlight specific features (bottom image) in the turbulent high-speed flows as different parcels of gas crashed into each other and as ultraviolet light from the star tore atoms in the gas apart. There is a long and interesting story that we are piecing together about the history of this PN that will come from this image. Once that story is complete, we will have learned a lot more about how stars spend their final years sending fusion-enriched matter back into space to seed new generations of stars, planets, and maybe even life.

But that story is not what I want you focus on right now.

Instead, I want you to take a minute or two to just let the incredible beauty of this object work its magic. For all our scientific narratives of stars and evolution and gas dynamics, this “Butterfly Nebula” is really no different from anything else we encounter in nature that makes us stop in our tracks with its beauty.

Whether it’s a tree on fire with fall colors, fields of sunflowers standing tall and yellow, or a butterfly looping around our chair on a summer day, the world has objects in it that can lift us out of our day-to-day concerns and remind us that there is more. There is more than our worries over jobs, money, relationships, and all the minutiae of life. That is what beauty does. That is how it works.

So how strange is it, then, to find that same experience in an object that exists 3000 light-years away and is, itself, a light-year across? The remarkable mix of symmetry and chaos in this thing, this titanic cosmic sculpture, evokes emotions that are so familiar to us, even though the object itself is as alien as possible. I think that familiarity — the experience of beauty we know so well — occurring in an environment that we can barely imagine holds an important message for us.

The joy of cosmic beauty

Yes, we can do and appreciate science for its humanitarian benefits. Yes, we can do and appreciate science for its ability to answer deep questions about the nature of reality. But achieving deeper experiences of the world through beauty is just as important a reason to do science. It is important because it reminds us that no matter how vast or distant or ancient, every part of the world is still ours. We are still part of it all, connected to it all. And that is something to be deeply thankful for.