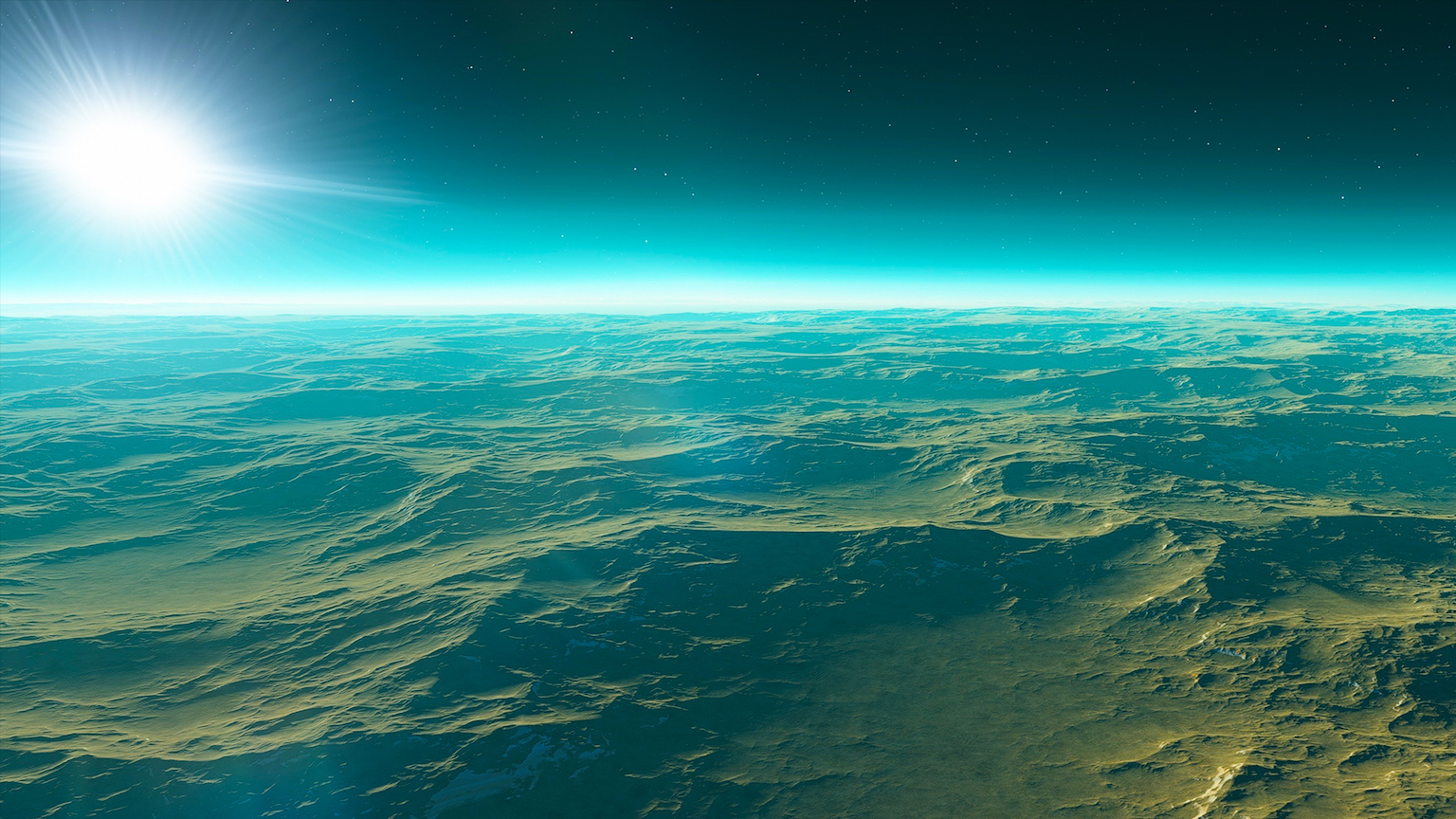

Exoplanets fill us with awesome wonder

- We now know that exoplanets are everywhere in the Universe.

- Ocean worlds. Snowball worlds. Desert worlds. Diamond worlds. If you can imagine it, it very well might exist.

- Science serves a lot of purposes, but one of its most important is to expand the vistas of our imagination.

Ocean worlds. Snowball worlds. Desert worlds. Diamond worlds. If you have been following the exoplanet news for the last couple of decades, you may have seen headlines about each of these kinds of planets. Using powerful telescopes, new techniques, and theoretical modeling, scientists have come to realize the wild diversity of planetary types nature has created. Last week, I had my own experience poking around in this wilderness, and it brought home the most important aspect of how we should think about all the exoplanets science is dropping at the doorsteps of our imagination.

I had traveled down to New York City to meet with an old friend of mine who is a very talented atmospheric physicist. He studies Earth’s climate but has recently developed an interest in exoplanets. After knowing each other since grad school, we decided it was time to start collaborating. We wandered around the West Village, comparing notes on the problems in the overlap between Earth science and exoplanet studies. Then the conversation drifted to rain.

Rainfall is a pretty basic process for planets.

The surface of Earth is heated by sunlight. That heat evaporates liquid water, turning it into a gas (water vapor). The water vapor is carried upward by large scale atmospheric motions called convection. Once the water vapor gets carried high enough, the surrounding air is so cold, that the vapor condenses back to liquid, leaving raindrops which fall back to Earth. It is a cycle that can get repeated as often as conditions on the planet allow.

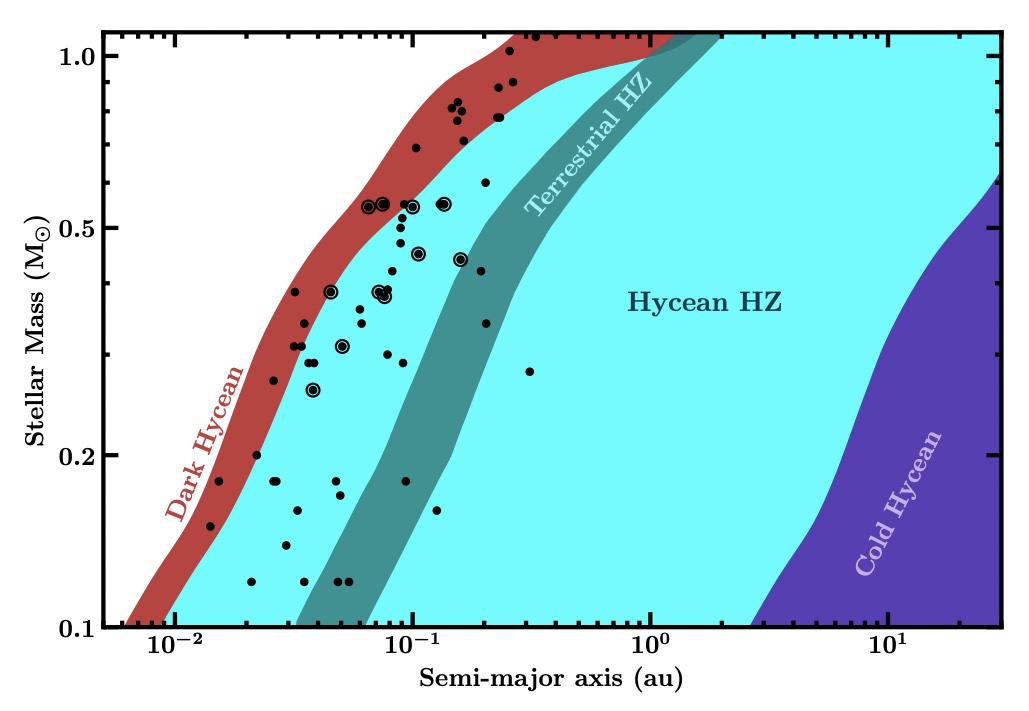

So, like I said, rainfall is a pretty basic process for planets. It could and should happen on any world in the habitable or “Goldilocks” zone of a solar system — that is, the zone of orbits where liquid water can exist on a planet’s surface. But rainfall also matters for the evolution of a planet. Rain erodes rocks, and rocks can store carbon, and carbon (in the form of carbon dioxide) is one of the main factors determining a planet’s climate (via the planet’s temperature).

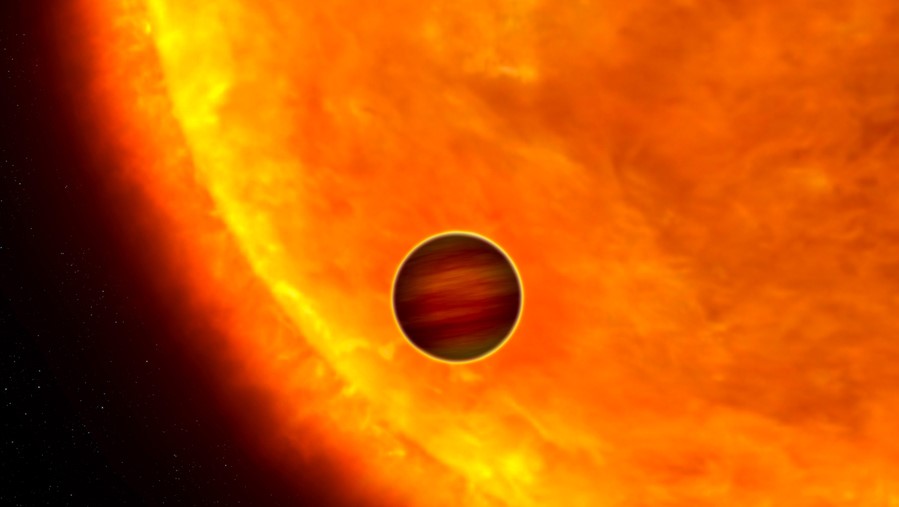

That is why once our conversation turned to rainfall, it stayed there. For the next hour or so, we began putting together ideas about how rainfall might work on other planets. How much rain do you get on a planet just like Earth but orbits 10% farther from its sun? How about 10% closer to its sun? How much rain do you get on a planet that orbits its sun at the same distance as Earth but is 10% heavier?

It was exciting throwing around ideas, trying to see how all this might affect the climate history of an exoplanet — including the possibilities for life. Eventually, it was time to go, but we left with the beginnings of a project.

It was only later that night, as I drifted off to sleep, that it came to me: Rainworld!

The image appeared, almost as of a dream, of landscapes eternally soaked in driving rains. Cliffsides beaten by sheets of wet wind. Plains forever topped by low-slung, scudding clouds that pelt the land with heavy drops. Oceans of heavy swells that never see the sun. For a few beautiful moments, the scientific discussions of the morning were transformed into a minds-eye view of the planetary reality. It was very beautiful. That brief moment reminded me of what is most important when we think about exoplanets, not as scientists but just as people.

They are places!

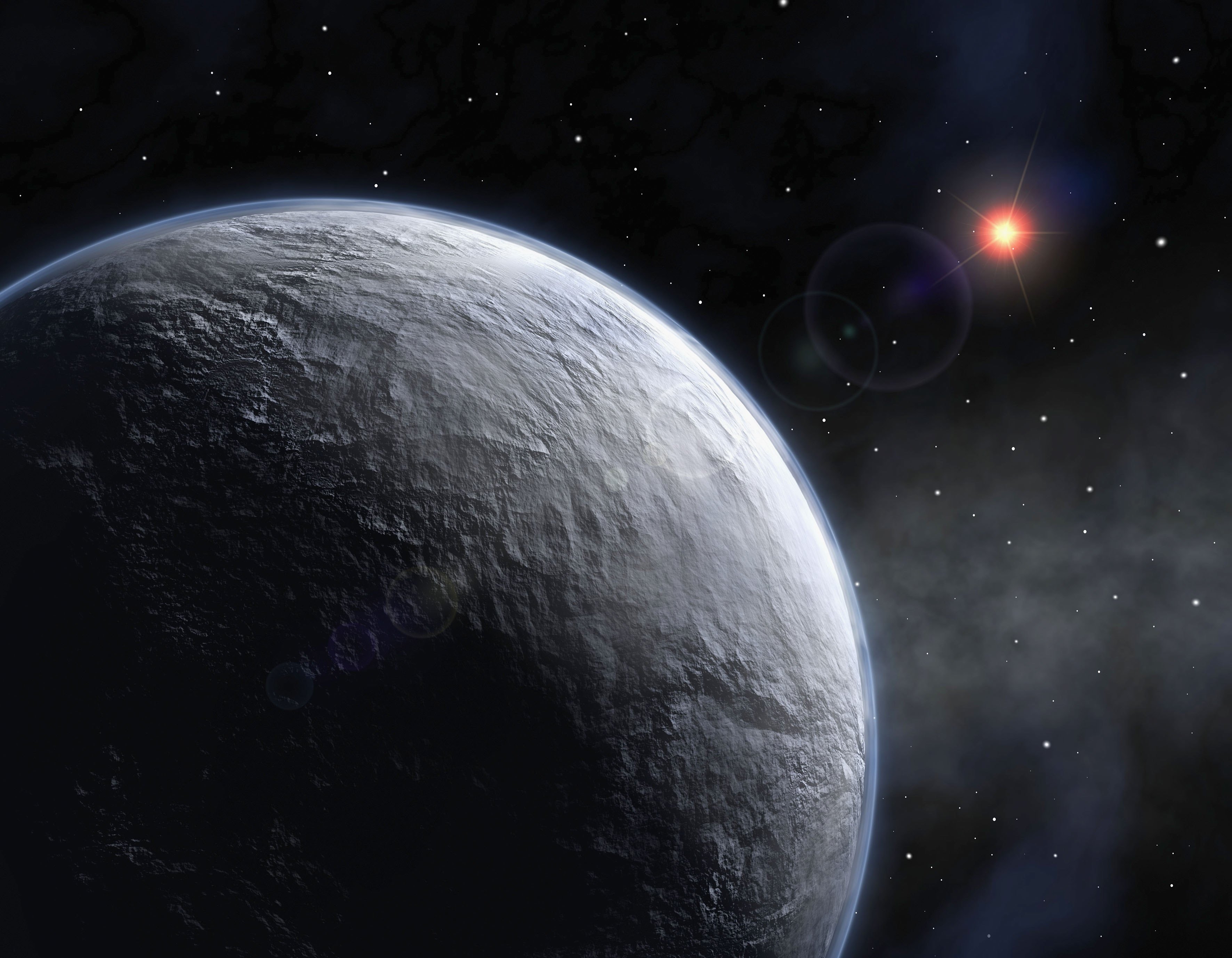

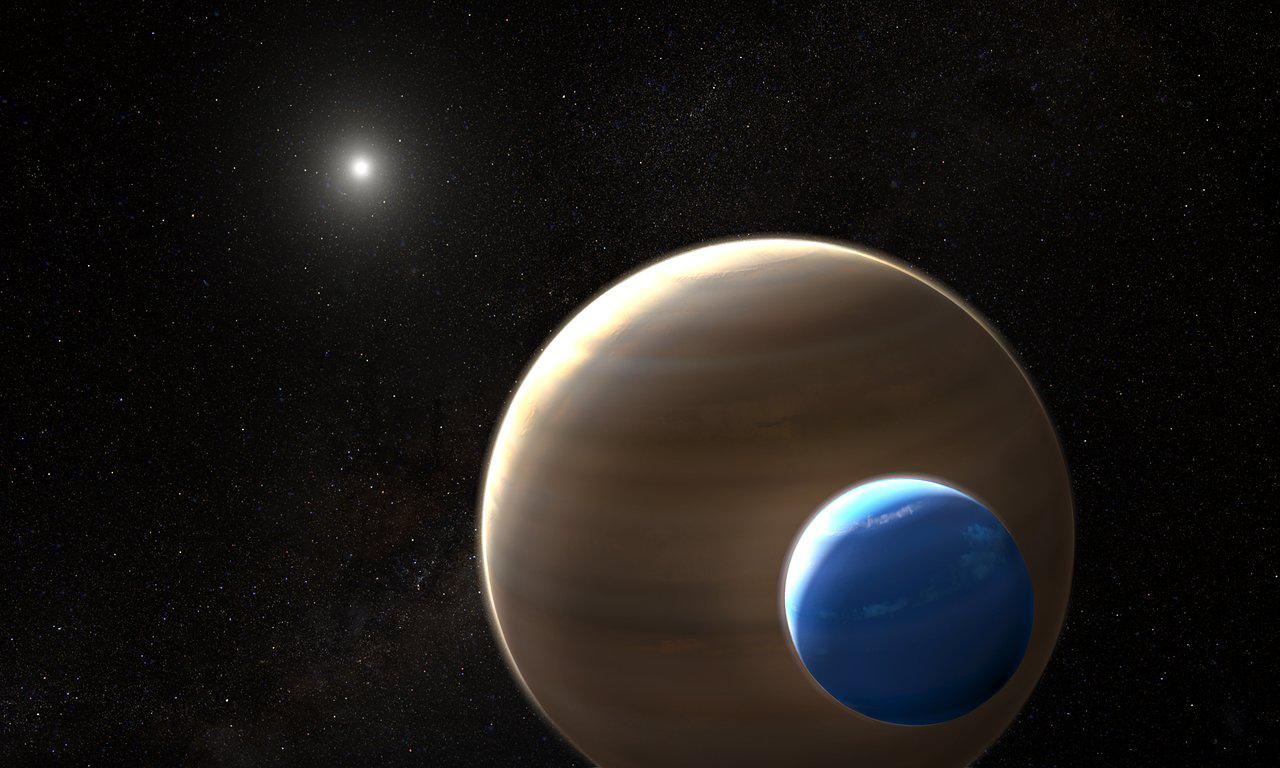

Science serves a lot of purposes, but one of its most important is to expand the vistas of our imagination. What exoplanet science shows us is that the Universe is full of worlds. These planets are both completely different and utterly like our own. They are different in ways that stir the imagination: worlds of only endless oceans, worlds entirely covered by ice, worlds of vast steaming jungles without any ice, worlds of rain. But they are also entirely like our own planet in that they are places you could be. They are places you can stand and look out and (in some cases) walk and (in some cases) climb and (in some cases) sail.

Even if you or I will never actually visit these distant worlds, we now know they exist. We now know they are out there. They are real, and for me there is so much wonder, hope, and excitement in that knowledge. And that is how to think about and why to think about exoplanets.