Why the truth of art is greater than the truth of science

- Art is as essential to understanding human nature as science. Art reveals the deep philosophical underpinnings that allow humans to unveil hidden truths.

- While humans are constrained by the world, we consistently push back against these constraints. Art, through mechanisms like irony, allows us to see the world differently and emancipate ourselves from limitations.

- The act of creating art is a profound inquiry into our relationship with the world. This recognition is foundational for true scientific understanding.

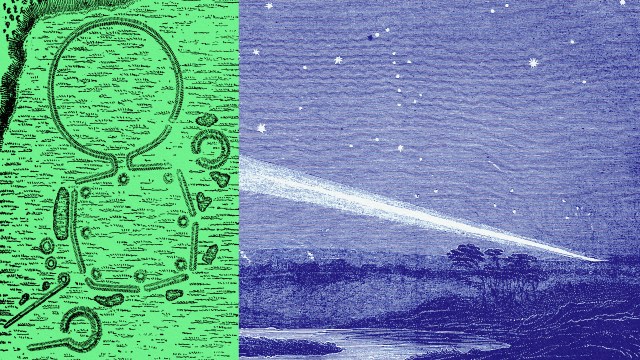

“At the very beginning of history, we find the extraordinary monuments of Paleolithic art, standing as a problem to all theories of human development, and a delicate test of their truth.”

—R.G. Collingwood

This quote and the problem it describes drives The Entanglement by Alva Noë, a new book on art, philosophy, and what it means to be human. Almost as far back as we want to go in the story of humanity, there is art standing in a central, pivotal location. The question that Noë, a philosopher at the University of California-Berkeley, wants to understand is simple: Why? Why is art so central to our development that we cannot tell the story of humanity without it?

The centrality of art

In the modern world, we tend to view science and technology as the most important achievements — the true pinnacles of human ability. While we acknowledge that art is something only humans do, it tends to get relegated to the domain of “mere” beauty or pleasure. In this view, art is important, in its own way, but it simply does not have the same sort of cosmic relevance as the theory of general relativity or the standard model of particle physics.

The key point of The Entanglement, however, is that this kind of hierarchy is a profound mistake. Art is just as much about revealing the essential as science is. You might even say that the making of art comes before science in reaching down to our very roots — those deep philosophical underpinnings that allow human beings the ability to unveil hidden truths.

The fact of art’s central place in human development speaks to the problem Collingwood identifies in the quote above. We are physically embodied. That is the central fact of our lives. We don’t start off as brains in a vat contemplating the perfect platonic abstractions of mathematical physics. Instead, we begin with the constraints of being in bodies. But being human also means we are constrained by our cultures. By this, I mean the simple fact that we emerge into the world as part of a community of other language users from whom we are given the shape of our world of experience. This includes the norms of social behavior and the tools that shape the material facts of daily life. From our earliest origins as Homo sapiens living in small tribes, we both have been made by the world as much we make it. And that is why art has always been central to human experience.

As Noë puts it: “To say that art and life are entangled is to propose not only that we make art out of life — that life supplies art’s raw materials — but further that art then works those materials over and changes them. Art makes life new” [emphasis added].

Freedom from constraints

What Noë means here is that while we are given the world and constrained by it, we always have pushed back against those constraints in a way that seeks to free us from them. Noë points to the example of language. We can use language to “speak plainly,” meaning to describe things and make plans that further our project of surviving in the world. But then comes the possibility of irony, the ability to use language in a way that subverts itself. In that subversion, what was plain, ordinary, and even habitual suddenly stands out on its own. The use of irony — one form of many that can be used in art — is a kind of attempt at emancipation from the brute facts of our embodiment. In this way, it is a key step that opens an entirely different way of encountering the world. As Noë says, art requires that “we work ourselves over and make ourselves anew, individually and ensemble.”

That “making ourselves anew” is why I find Noë’s ideas so compelling and relevant for science. For me, science is not simply the picking up of “facts” that are lying around. Instead, it’s a kind of sympathetic creative exchange with the world in which we are enmeshed through embodiment. The world is not simply “out there,” and science is not simply a view through “God’s eyes.” Instead, we are always entangled with the world.

What Noë shows is how that essential act of “making” art is more than just an act of pleasure. What it really encompasses is a radical act of inquiry into our entanglement. It’s the first recognition of the inescapable fact that it’s always us and the world. We recognize that fact by understanding that we have the possibility of re-seeing the world and remaking it through the making of art. For me, it’s only through that kind of recognition that true science and its abstractions become possible.