Why do we sleep? Scientists still don’t know

- Sleep seems to be a necessary process for all animals, yet scientists still aren’t quite sure why.

- One hypothesis says that sleep serves something like a cleaning process, clearing from the brain damaged molecules and toxic proteins that build up while we’re awake.

- Although the reasons why we sleep remain unclear, studies have consistently shown that not getting enough sleep can negatively impact many aspects of our physical and mental health.

All animals sleep, even the diminutive roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans. Tinkering scientists have tried to genetically engineer the act out of laboratory mice, but all attempts have failed; even severing sleep-promoting circuits in their brains does not remove rest entirely. Sleep seems to be fundamental. The simple yet grand question is why.

The effort to find an answer has attracted the learned attention of Imperial College London Professors Nicholas P. Franks and William Wisden. Together, they operate the Franks-Wisden Lab, using molecular genetics and behavioral analysis in mice to explore the drivers and functions behind sleep. They hope this pursuit will lead to improved anaesthetics and treatments for dementia.

In a recent review published in the journal Science, Franks and Wisden shared a few of the things they’ve learned over almost a decade of research. For starters, they have an educated hunch as to sleep’s true purpose: to conduct basic structural or metabolic processes that allow the brain to function normally when we’re awake.

“Much like the cleaning teams who move into empty offices during the night and whose work would be almost impossible during the daytime bustle, some essential and restorative process is underway after we slip into sleep, when normal brain function is at least partly suspended,” they wrote.

Previous studies suggest that one of these janitorial roles is a cleansing of damaged molecules and toxic proteins that build up during wakefulness, a side effect of the brain’s metabolically intensive activity. In 2013, scientists watched the brains of sleeping mice and witnessed the space between their brain cells widen, greatly increasing fluid flow. Six years later, researchers watched the process occur in humans, and in even greater detail. The Boston University scientists saw blood flow out of sleeping human brains and cerebrospinal fluid rush in. It continued to do so in “pulsing” waves.

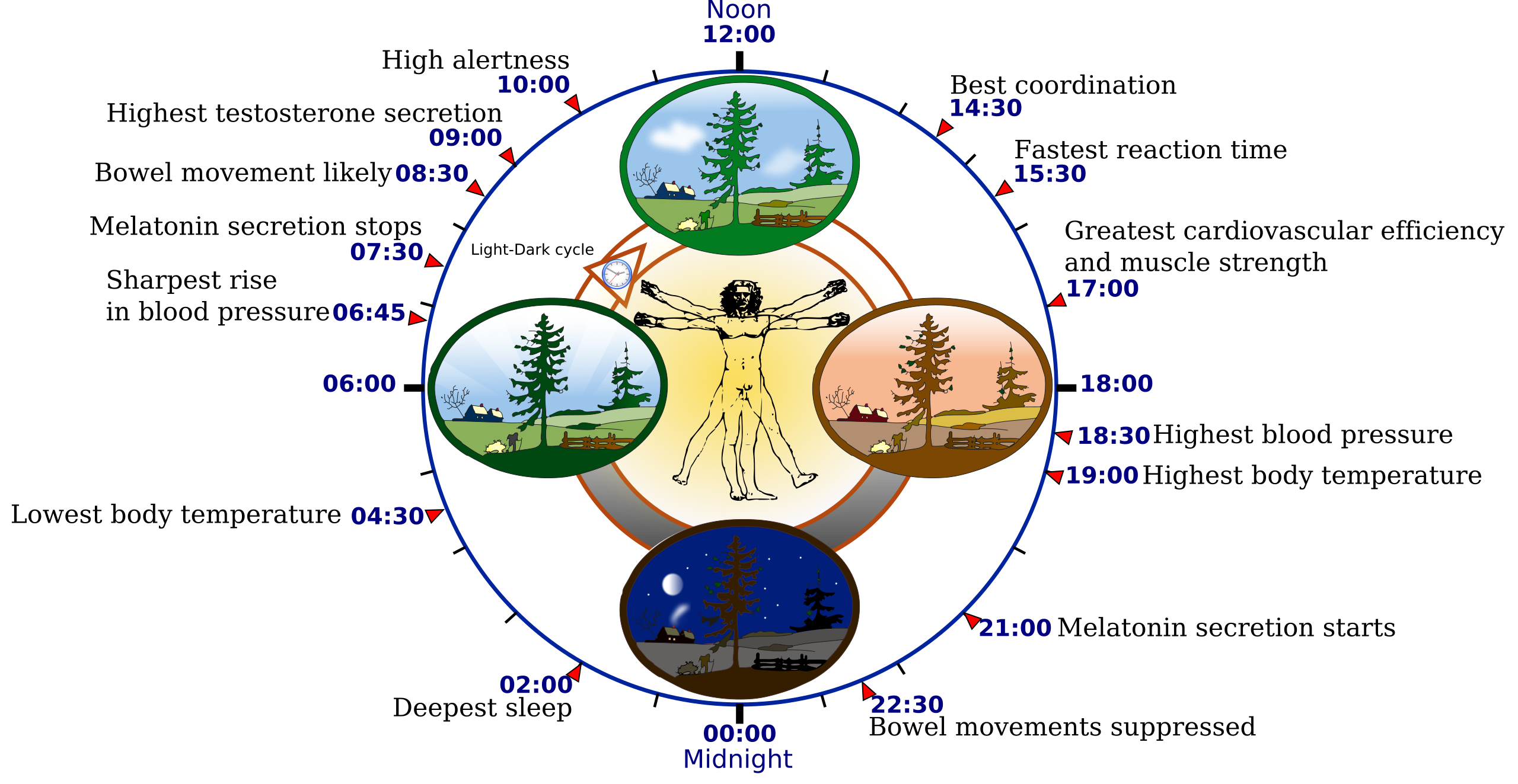

Fascinatingly, the temperature of sleeping brains drops considerably, by about two degrees Celsius. Although this doesn’t seem to have much to do with the “washing” of the brain, it could allow for some sort of synaptic remodeling to occur, Franks and Wisden hypothesize.

We sleep in stages, and one of the most talked-about stages is called rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, popular because it’s when we dream most vividly. But, interestingly, Franks and Wisden say that this type of sleep – in contrast to non-REM, doesn’t seem to be essential.

“It is possible to genetically ablate all REM sleep in laboratory mice with no apparent ill effects,” they wrote.

Instead, Franks and Wisden hypothesize that REM sleep may be a testing mechanism for the brain to see if the restorative function carried out during non-REM sleep was successful.

“If it has, we wake up.”

That’s a nifty explanation for why we restfully wake-up, but what explains why we go to sleep in the first place?

“When we are strongly sleep deprived, we become highly motivated to find a way to sleep, in the same way that strong thirst and hunger motivate us to drink and eat. If sleep deprived enough, we will do almost anything to sleep,” Franks and Wisden wrote.

Like body weight and hydration, sleep seems to be “homeostatic” — there’s a level that our body prefers to maintain: not too much, not too little. While various neuronal circuits in the brain have been implicated in maintaining this balance, it’s still unclear how exactly they determine it and eventually trigger sleep itself. What we do know is that no matter how hard we try to stay awake, sleep will eventually take hold.

But rather than being captured by sleep, Americans should really seek it out. Adults need seven or more hours of sleep per night for optimal health and wellbeing, according to the CDC. On average, we manage less than six. While sleep’s precise purposes still evade our knowledge, we know that, whatever they are, they vastly improve cognitive function, mood, and physical performance. If sleep were a drug, we’d be clamoring for it.