Throwback Thursday: What the James Webb Space Telescope means

Why the biggest, most expensive NASA telescope ever is also the most important thing we’ve ever attempted.

“Where there is an observatory and a telescope, we expect that any eyes will see new worlds at once.” –Henry David Thoreau

The night sky is our greatest glimpse of what lies out there, beyond our own world, in the expanse of space we know as our Universe.

With our naked eyes, we are able to see a few thousand stars, the Moon, five planets, the Milky Way and a few other nebulous “clouds” or “fuzzballs.” And with just our naked eyes alone, we could learn some remarkable things about the Universe, including the basic structure of our Solar System and the orbital motion of the planets. Based on our understanding of brightness and distance, we could also — if we assumed that the Sun was just a star — roughly measure the distance to the stars, too.

But we are not bound by the limits of our eyes any longer.

Thanks to the telescope! Here on Earth, we’ve been building telescopes and using them for astronomy for just over 400 years now. Initially used to hunt for comets and for exciting features on the planets (such as moons, rings, and atmospheres), it wasn’t long before we discovered that there’s a whole, well, Universe out there for us to discover.

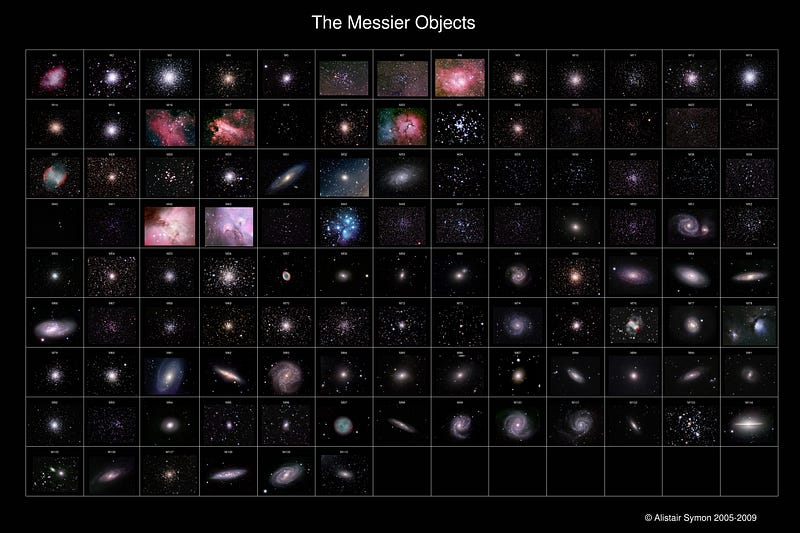

In addition to not just thousands — but billions of stars — we started discovering very strange objects. Initially appearing to be “smudges” in the sky, we built successively larger and more powerful telescopes, built them at higher altitudes to give us less atmosphere to contend with, and developed more and more powerful cameras and optical technologies to help us see what’s really out there.

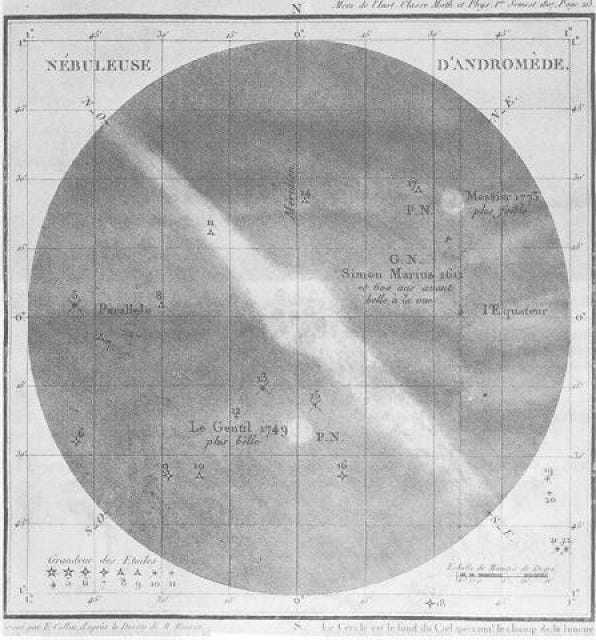

To see how things have improved over time, take a look at Charles Messier’s drawing of one of the largest “smudges” in the sky, M31, from his observations in 1764.

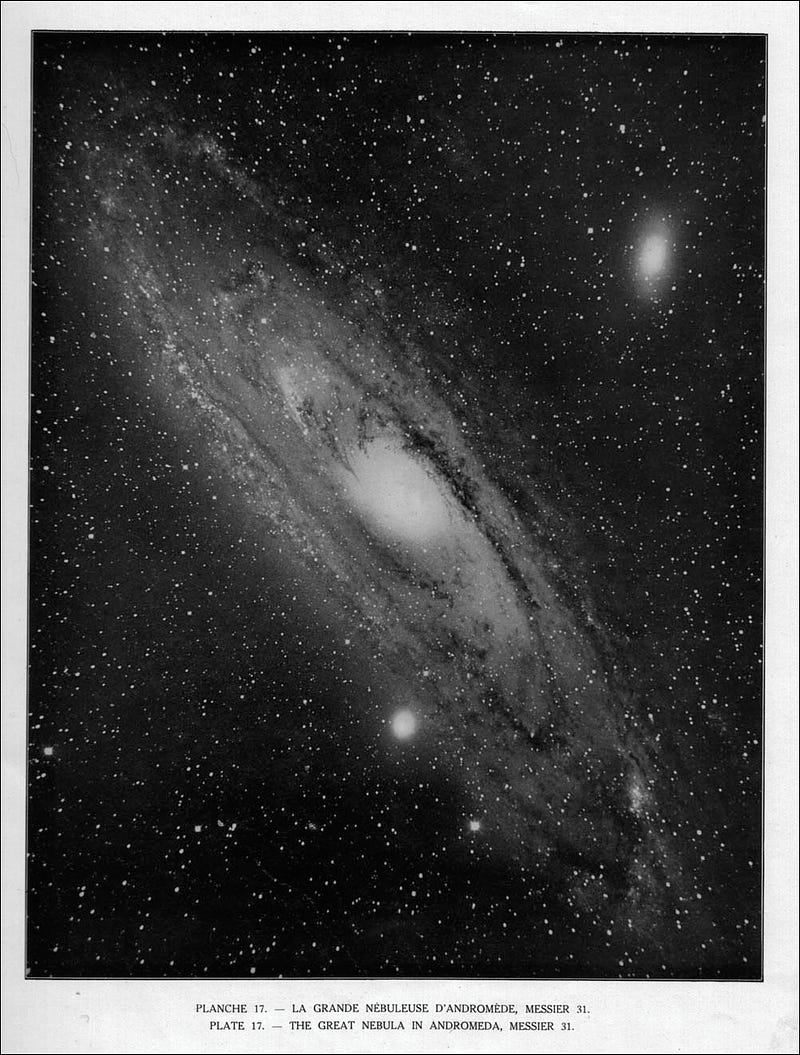

By 1887, technology had improved enough that we could take photographs of this spectacular nebula, and thanks to the power of the internet, Isaac Roberts’ famous photograph is right here for you to see.

And in 1929, Hubble used his data from observing this very same nebula to determine that this was no conventional nebula from within our own galaxy, but was actually its own “island Universe,” millions of light years away! In no small part, this was because telescope technology, had improved tremendously by 1929, as the image of M31 (below, by Bob Olson) shows.

Over the 20th century, new types of stars — like pulsars — were discovered. We found new types of deep space objects, such as quasars, the microwave radiation that was the telltale leftover glow from the Big Bang, and huge clusters and superclusters of galaxies.

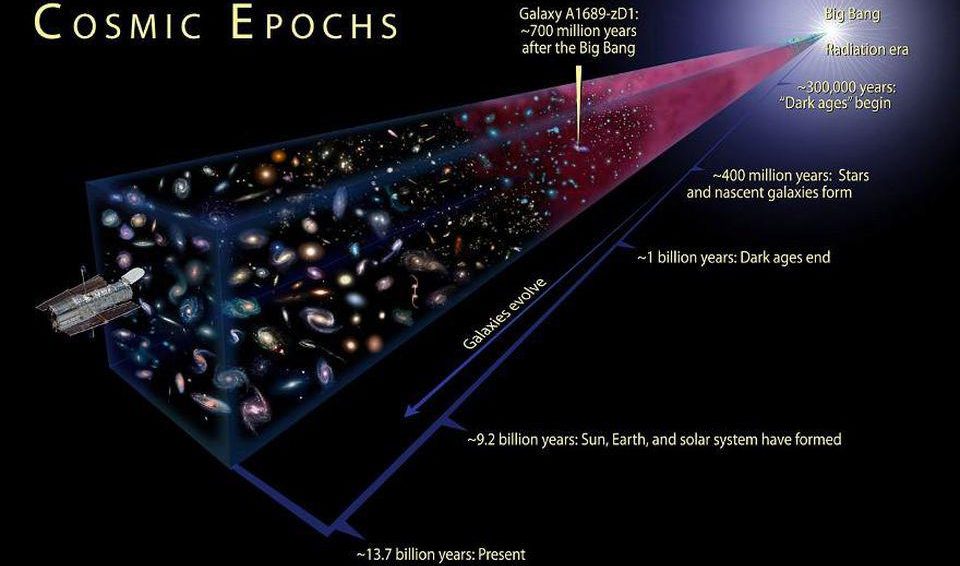

Our view of the Universe had gone from a few thousand stars just a few hundred light-years in size to one billions of light years in scale, populated by billions of galaxies, each one containing hundreds of billions of stars, hundreds (or thousands) of globular clusters, with each star — quite possibly — containing planets of their own.

And then, in 1990, we went to space. The Hubble Space Telescope literally changed our view of the Universe. Without the atmosphere to contend with, not only were there no worries about clouds, turbulent air, or light pollution, but we could see farther, deeper and for longer amounts of time than we ever could before.

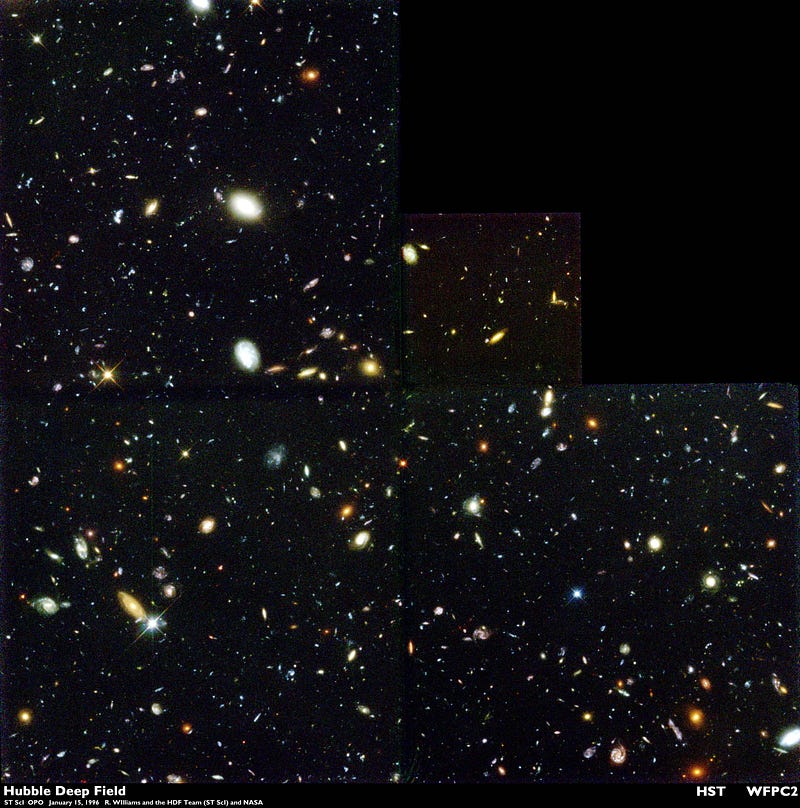

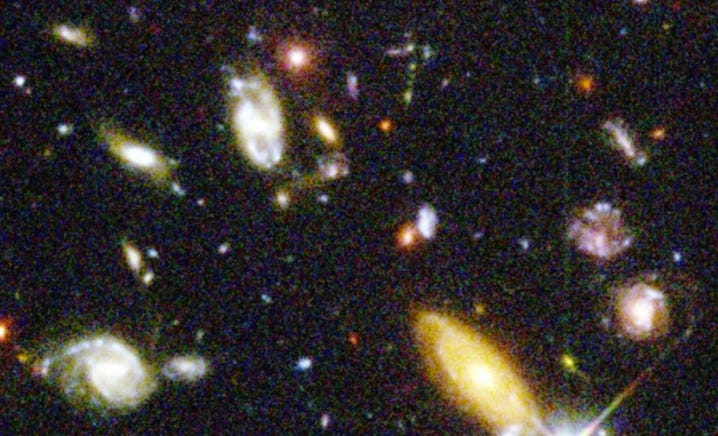

In perhaps Hubble’s most spectacular discovery, it was pointed at this very dark, unpopulated patch of sky. With something like 5 or 6 known, very faint stars, no gas, no dust, no nebulae or galaxies or anything else discovered in the background, this was one of the most daring observations ever.

Because it was scheduled to go on for days. Imagine taking the most powerful tool in the world and just aiming at emptiness, monopolizing it for a huge stretch of time, uncertain that you’ll even find a single thing of interest. When the data finally came in, here were the results.

Now, with the exception of a few stars (easily identifiable by the “spikes” emanating from them), everything in this image is a newly discovered galaxy. Even looking at a minuscule segment of the full-resolution version of this image shows a whole slew of beautiful galaxies.

And “big deal,” you might say, “the 1929 picture is at least as good!” Yes, but these galaxies are not two million light years away like Andromeda is, they are many billions of light years distant.

Looking for distant galaxies is just one example, of course. Hubble has also been used to find the most distant supernovae in the Universe, find the earliest galaxies and quasars, and — as a surprise — discover that the Universe’s expansion is accelerating! All because we invested in looking at the Universe in a way we never had before.

That isn’t to even mention the unprecedented, high-resolution, beautiful pictures that Hubble has taken, such as of the Pillars of Creation, above, or the other advances we’ve made in the science of finding planets, learning about star formation, or peering into the hearts of some of the most spectacular objects in the Universe, like star cluster NGC 290, below.

But Hubble is over 20 years old now. We’re at the limit of what we can do with it, and without the shuttle (whose last flight was today), we can no longer service it.

So what’s the next step?

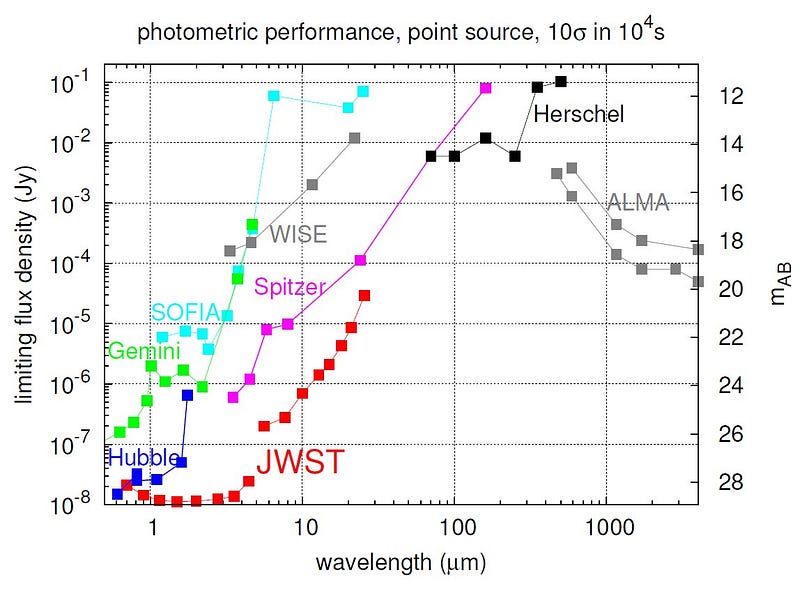

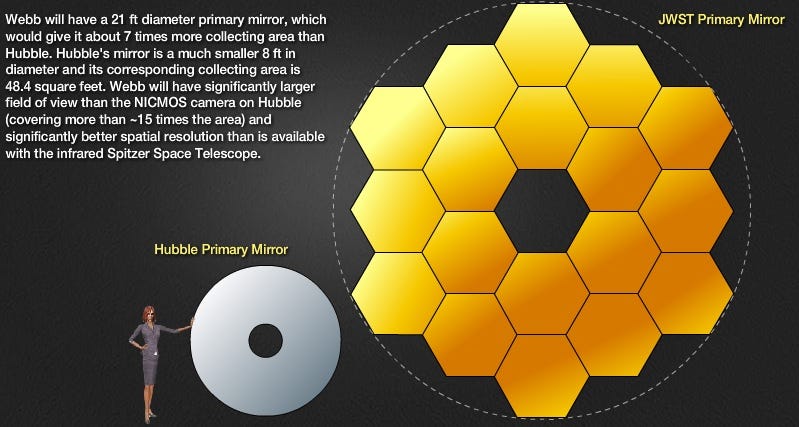

The James Webb Space Telescope! With a 6.5-meter-wide set of mirrors for gathering light, this new telescope will leave Hubble in the dust. With a huge range of wavelengths it can cover, from a green color far into the infrared, it will be more sensitive, by a factor of about 100, than all the other telescopes that have come before it.

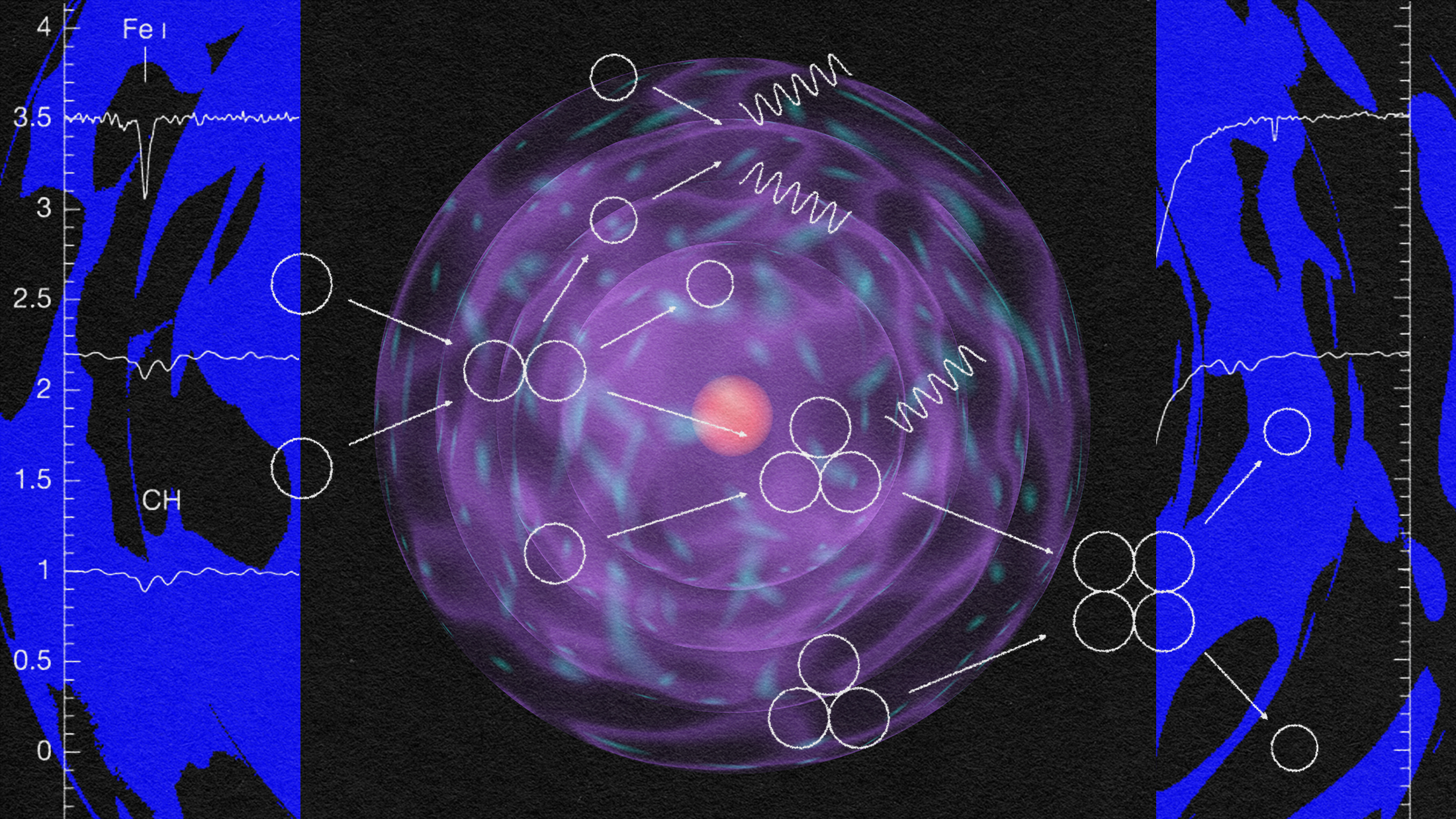

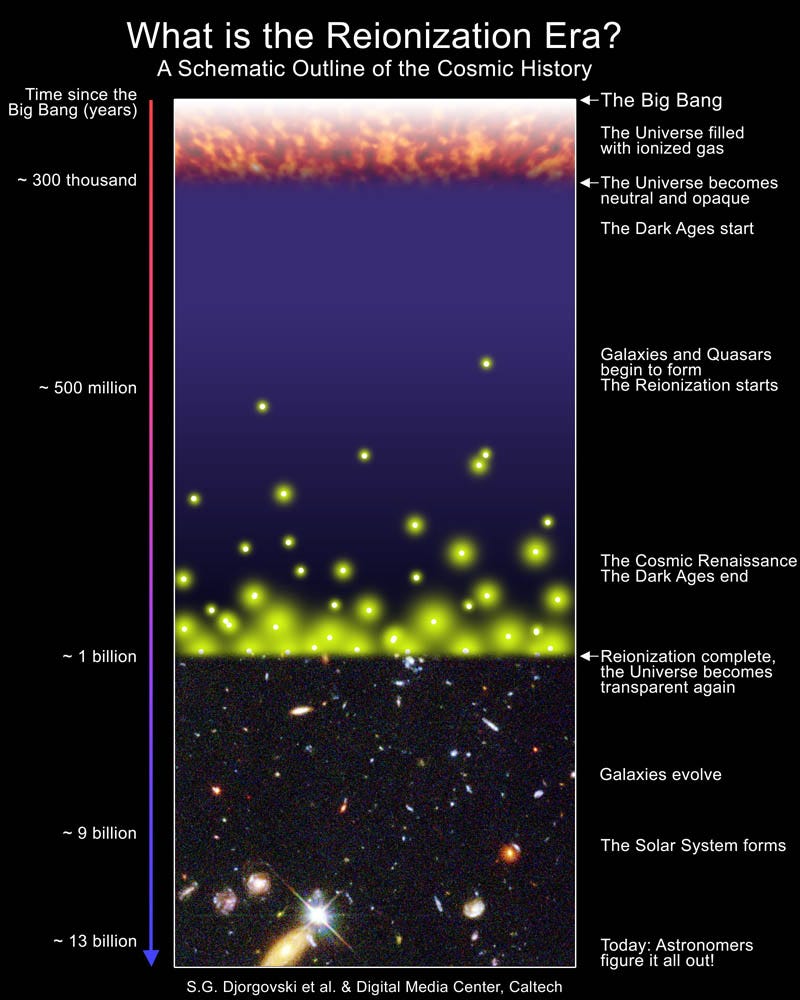

And we already know some of the new things we’ll be able to observe with it. Even more distant galaxies and supernovae than ever before. The formation of solar systems. Direct images of individual, Earth-sized planets around about half the stars on this list, including the ability to detect water, atmospheres and surface features. And — for the first time — the ability to directly measure the first stars formed in our Universe.

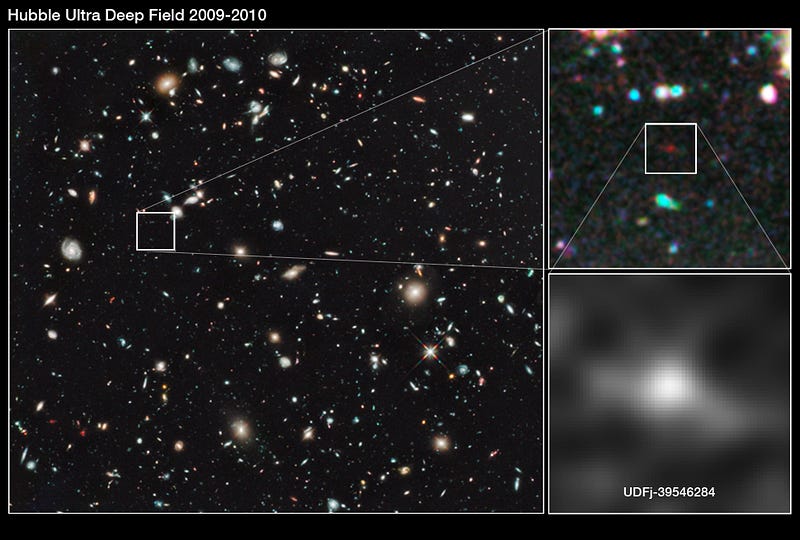

That means “seeing” into what we currently call the Universe’s “Dark Ages,” something we can only do at the infrared wavelengths that James Webb is sensitive to, and only from space, since our atmosphere absorbs those wavelengths. The current cosmic record-holder for most distant galaxy comes from Hubble, and is from a time when the Universe was just 4% of its current age; this galaxy is some 33 billion light-years away at present.

But there are even more distant ones out there, and these are the stars and galaxies that James Webb is going to be sensitive to and Hubble isn’t. It’s the right tool for the job, and the only tool we’re even considering for it. How far is the most distant galaxy really? It will take this telescope to find out.

There are amazing things out there waiting to be discovered, and the James Webb Telescope is something like 85% complete. It just needs to be finished and launched; this is the future of astronomy and astrophysics.

So don’t forget how truly awesome this Universe is, and how precious and rare our chances are to glimpse and understand it just a little bit better. Let’s make sure we see this investment all the way through, and keep the components’ construction, testing and assembly on schedule.

The rewards — of the the entire Universe at our fingertips — are simply too great to pass up.