Hubble’s latest breakthrough reveals trillions of unknown galaxies in the Universe

How many galaxies are there in the observable Universe? For the first time, we don’t just have a ‘lower limit’ — we have an answer.

“Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.” –Carl Sagan

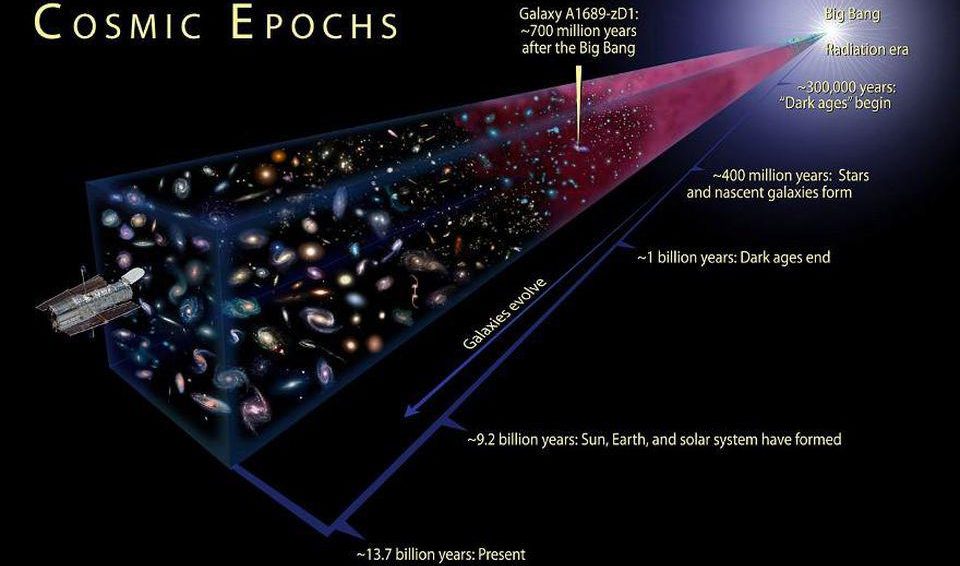

How many galaxies are there in the observable Universe? Ever since we first uncovered the Big Bang origins of our cosmos, we knew that the number would be finite, since a signal from a galaxy moving even at the speed of light can only reach a certain distance. But without a telescope capable of reaching all the way back to the Big Bang itself, any number we reached from observations would only be a lower limit, not an accurate estimate. Previously, that’s exactly what astronomers working with the Hubble Space Telescope had done, revealing a Universe with hundreds of billions of galaxies, at least. But thanks to a new study by the CANDELS team, that estimate has been increased to two trillion, an increase of more than a factor of 10. Here’s the story of how we got there.

The Hubble Space Telescope was launched in 1990, its mirror was defective. A servicing mission a few years later led to the most powerful telescope humanity had ever seen. With the greatest-ever optical systems and observing power at its disposal, a very unusual proposal was greenlit. A team was going to point Hubble at a patch of sky without an observing target. Rather than observe a planet, star, nebula, cluster or galaxy, Hubble was going to observe the black void of empty space. By pointing at a patch of sky with nothing in it:

- no bright stars,

- no gas clouds,

- no nebulae,

- no known galaxies,

- no clusters,

astronomers were hoping to find out whether empty space was trulyempty, or whether, as the Big Bang and the cosmological principle predicted, a plethora of galaxies from the distant Universe would be revealed to us.

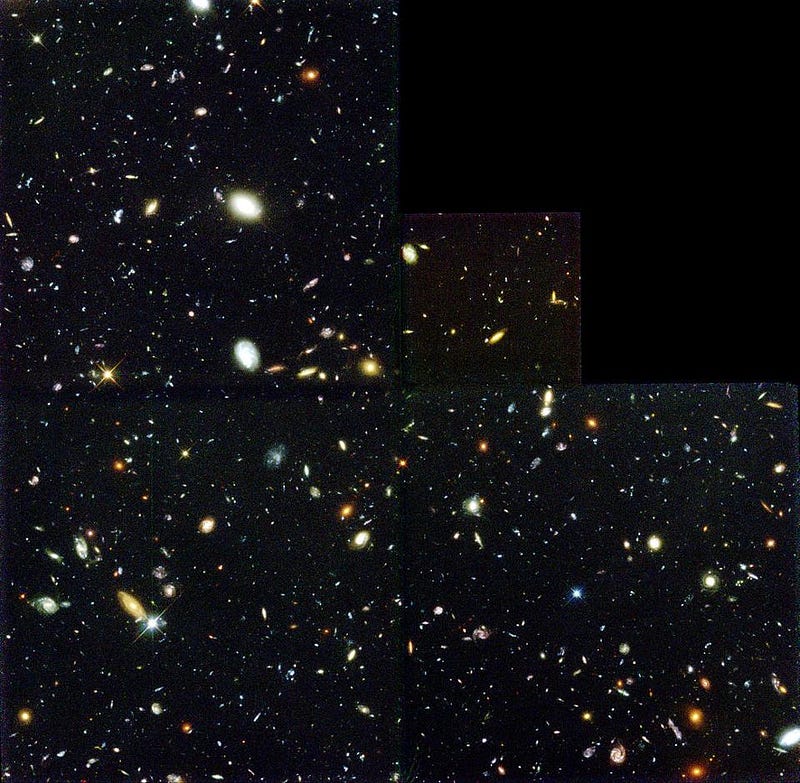

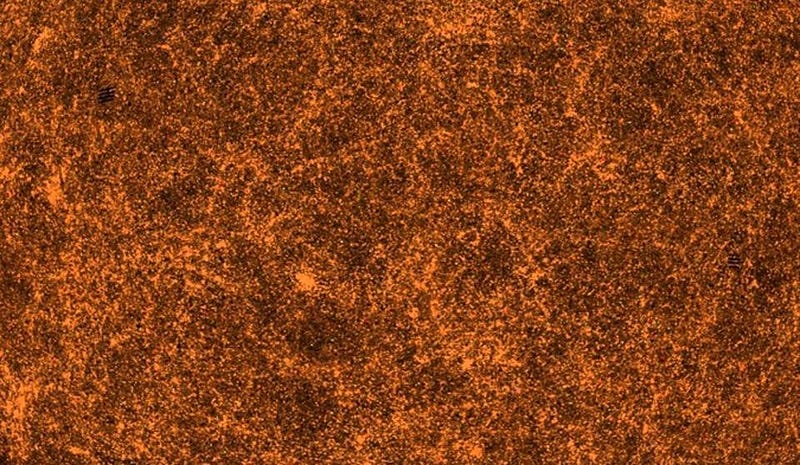

The Hubble Space Telescope orbits the Earth approximately once every 90 minutes, or 18 times per day. Over a total of 342 cycles (where each cycle is a half-an-orbit), it images this exact patch of sky, a patch where only maybe five or six very faint stars within our galaxy lived. It pointed away from the galactic plane, out into intergalactic space, at a blank location known to be empty to the limits of our largest and most advanced ground based telescopes. And after a total of nearly 10 days‘ worth of light had been gathered in multiple different color filters, they composited the image and released it to the world. Here’s what it saw.

In this tiny region of space, where zero known galaxies were seen previously, we now had discovered around 3,000. With the exception of about five or six points showing diffraction spikes (the “pointy” features), which are stars within the Milky Way, every single point of light in this image is a galaxy. This is the Hubble Deep Field.

This was so remarkable that follow-up images were taken, with deeper views, wider angles, longer wavelength ranges and longer observing times. The Ultra Deep Field broke the previous record, and then North and South fields were taken as well, demonstrating that the Universe has similar galaxy counts in opposite directions. Hubble’s Frontier Fields program went deep over a large field of view, showing that the Universe was similar over larger volumes. And most recently, as of 2012, an even deeper version was created, using a more advanced set of cameras and optics, and a total of 23 days worth of observing: the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field (XDF).

This last image, consisting of a region of space barely a thousandth of a square degree on the sky — so small it would take thirty-two-million of them to fill the entire sky — contains a whopping 5,500 galaxies, the most distant of which have had their light traveling towards us for some 13 billion years, or more than 90% the present age of the Universe. Extrapolating this over the entire sky, we find that there are 170 billion galaxies in the observable Universe, and that was just a lower limit.

https://players.brightcove.net/2097119709001/4kXWOFbfYx_default/index.html?videoId=4884483404001

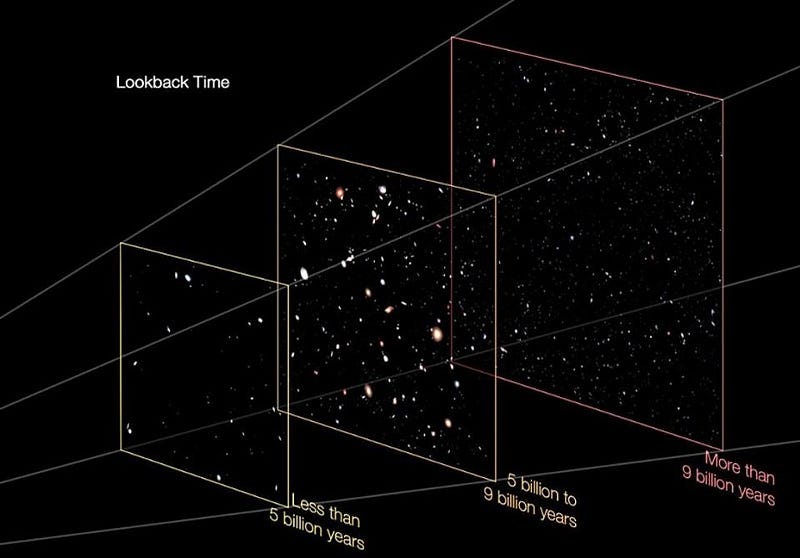

With all the data that Hubble has taken, not to mention other observatories, we can take these deep views of the Universe and a few other pieces of knowledge to construct a 3D map of a “slice” of the Universe. We’re not merely seeing a snapshot of the sky, but galaxies that are near, intermediate and ultra-distant. Even at that, we’re only seeing the ones that are easiest to see. By assigning distances to all of the observed galaxies in a particular portion of space, we can compute what the overall spatial density of galaxies is, including an estimate for how many other galaxies must be there that we can’t see, simply because they’re too faint or too distant.

In a new result out this week, a team led by Christopher Conselice of the University of Nottingham completed their work, and what they found was simultaneously wonderful and powerful: that as great as Hubble is, it only directly observed about 10% of what’s out there. Instead of 170 billion galaxies in the observable Universe, there are likely more than two trillion, each containing an average of 100 billion stars or so. Especially of interest is this surprising fact: the more distant Universe had greater numbers and densities of galaxies, which have since merged together to form fewer but more massive galaxies. The greatest numbers of galaxies, in other words, are both ultra-distant and ultra-faint. According to Conselice,

These results are powerful evidence that a significant galaxy evolution has taken place throughout the universe’s history, which dramatically reduced the number of galaxies through mergers between them — thus reducing their total number.

Beginning in just two years, the James Webb Space Telescope, a larger and longer-wavelength successor to Hubble, will finally begin to study these unseen objects directly. The Universe is full of galaxies, and for the first time we actually have an accurate estimate of how many it’s truly filled with. The next step is to begin taking measurements, and to finally uncover, with real data, how the Universe evolved and came to be the way it is today. Despite not bringing us all the way there, the Hubble Space Telescope continues to reveal answers about the deepest questions in the Universe. Even, remarkably, when it can’t see the answer directly.

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!