He’s on fire! How the hot hand helped Golden State become NBA champions

Long thought to be a fallacy, new analysis shows the ‘hot hand’ is real, and Klay Thompson has it.

“Success isn’t a result of spontaneous combustion. You must set yourself on fire.” –Arnold Glascow

The hot hand is a myth, like betting ‘red’ after a string of ‘black’ results on a roulette wheel, or betting on a coin flip turning up ‘heads’ after a bunch of ‘tails’ in a row. If you ask, “What are the odds that Steph Curry, LeBron James, or Kevin Durant make their next shot,” you know that if they’re a 50% shooter, the odds are probably 50/50. But what if the idea of going on a streak had some merit? What if you make three or four baskets in a row, previously? Could the odds of your success on the next shot possibly be different? According to NBA statistics — and mathematics — the answer is actually yes.

Let’s say you’re studying the game, looking to know whether there’s a chance of a streak in your favorite player’s future. They come out of the locker room for halftime, and you missed the first four minutes of the quarter. You return to the game and you find out that Curry has attempted three shots already. “Did he make a shot,” you ask? “Yes,” your friend tells you, “I remember I saw him make the second shot.” So you immediately start wondering to yourself if Curry made the third shot, and if there’s a streak happening (or about to happen) here.

The thing is, you know, if he took three shots, there are eight possible outcomes:

- Make, Make, Make. (Active streak: 3)

- Make, Make, miss. (Inactive streak.)

- Make, miss, Make. (Active streak: 1)

- Make, miss, miss. (Inactive streak.)

- miss, Make, Make. (Active streak: 2)

- miss, Make, miss. (Inactive streak.)

- miss, miss, Make. (Active streak: 1)

- miss, miss, miss. (Inactive streak.)

Based on the information your friend gave you, you know that only four possibilities are valid now: an active streak of 3, an active streak of 2, or two chances of an inactive streak. You have four possibilities, and 50% of them give you an active streak with a chance for more, while 50% don’t. You might think, if Curry is a 50% shooter, this is right in line with what you expect.

But what if you biased yourself, just by the way you phrased the question? You’re looking for ‘winning’ streaks, right? And so when you asked “Did he make a shot,” you only began paying attention because the answer was “yes.” But in reality, for one out of every eight times, the answer will be “no, he didn’t make any,” but you didn’t pay attention to those. Instead, you just focused on the 7/8ths of the time where a shot was made. And if, when your friend says, “I remember I saw him make the second shot,” they’re just picking a made shot at random, then what are the odds they would tell you that? Well, there are four possibilities again, but they’re not the same:

- Make, Make, Make. (Active streak: 3) — 33% chance, as your friend could have remembered the 1st or 3rd make just as easily.

- Make, Make, miss. (Inactive streak) — 50% chance, as your friend could have remembered the 1st make just as easily.

- miss, Make, Make. (Active streak: 2) — 50% chance, as your friend could have remembered the 3rd make just as easily.

- miss, Make, miss. (Inactive streak) — 100% chance, as your friend only had one make they could have remembered.

If you weight these probabilities successfully, now, you’ll find that there’s only a 36% chance that Curry is on an active streak, and a 64% chance that the streak is already over.

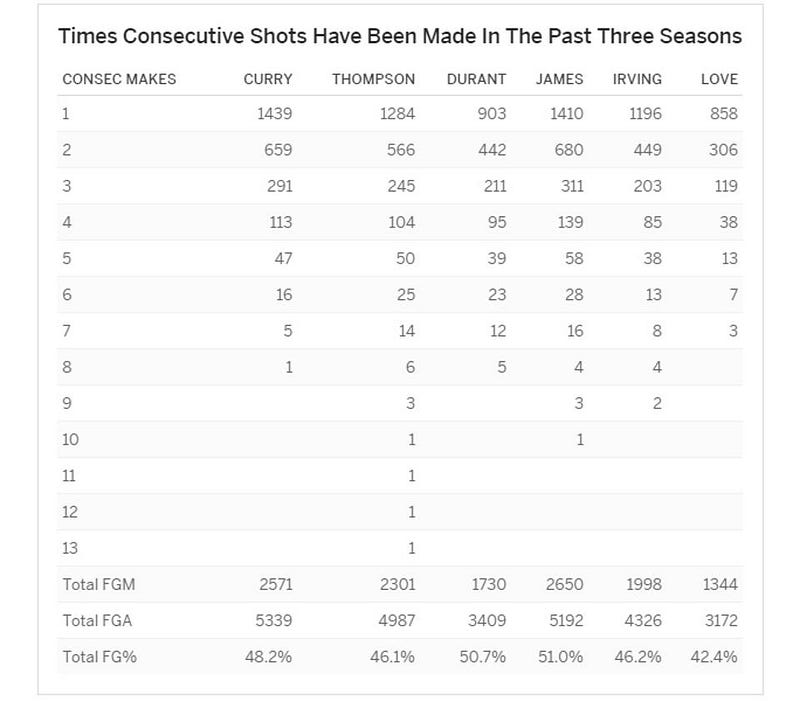

This is a stunning example of what scientists call “selection bias,” where you’ve restricted the chances of various possible outcomes just in the way you’ve obtained information about your data. There was a cognitive psychology paper published back in 1985 about the fallacy of the “hot hand” in the NBA, and their statistics showed that the hot hand was a myth. In fact, if you look at the chart above, you’ll notice that there’s a drop-off of more than 50% (in most cases, significantly more than 50%) in each player’s success rate in hitting that next tier of a long hot streak. “Myth confirmed,” you conclude.

Not so fast! 30 years after that study first came out, two economists, Joshua Miller and Adam Sanjurjo, showed that there is a selection bias when you’re looking at streaks in the NBA. When you’re picking out which shots you look at in a problem, and those shots are conditional on the sequence of other shots made before it, you change the game, which effectively suppresses the likelihood of continuing the streak. And while it’s not as bad an effect as the makes-and-misses we laid out above, it needs to be accounted for.

When you do, you not only find that the “hot hand” exists, but that some players really are streaky shooters, more than others, and do get hot. Curry is one of them, but so are/were Craig Hodges, Kyle Korver, and Ray Allen. In fact, when basketball players are asked to rate which of their teammates were most likely to get hot and go on a streak, they were aware of which players really are streaky shooters like that.

When you do your statistics (and your averaging) correctly, you find that many NBA players really are streakier shooters than others. Klay Thompson may be the streakiest shooter of all, but Steph Curry, LeBron James, and Kyrie Irving all “get hot” in a streaky way that goes beyond what their normal shooting percentages would indicate. A player getting hot at the right time can help their team tremendously, and now that we’re finally doing our statistics right, we’re finding something surprising but robust: for at least some NBA players, the effect of the hot hand is real.

And when you’re ‘on fire’ like that, may all your opponents beware. After all, in 1967 over the span of multiple games, Wilt Chamberlain made a still-NBA record 35 consecutive field goals. Good luck toppling that one, Warriors.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.