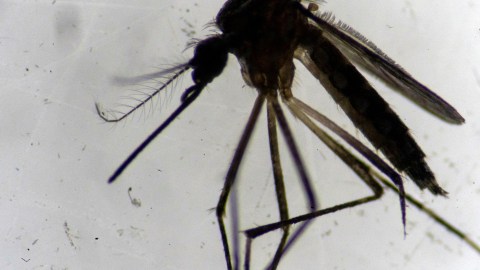

Mosquitoes’ taste for blood is finally explained

Credit: MAURO PIMENTEL / AFP/ Getty Images

- A recent study demonstrates that mosquito brains react to the taste of human blood in strange ways.

- Some neurons only activated when presented with all four flavor elements. This is thought to be a unique adaptation.

- The findings may lead to novel ways to prevent mosquito bites.

Mosquitoes suck. The diseases that they spread kill 500,000 people a year, and some of them, such as Malaria and Zika, are noted for being remarkably unpleasant even when they don’t kill you.

Female mosquitoes don’t usually suck blood—they sustain themselves on nectar, but switch to the red stuff when they need to lay eggs. They work harder to drink blood than nectar, drawing it in with much greater force. How they know the difference between the two has remained unknown, until now.

A new study published in Neuron sheds light on how mosquitoes determine what they’re eating and offers a potential solution to their disease spreading ways.

In a move dubbed a “tour de force” by other scientists involved in mosquito research, the researchers genetically modified mosquitoes so that specific neurons associated with taste lit up florescent tags when activated. They then offered these Franken-mosquitos a variety of tempting drinks to see if they would consume them and, if so, what taste neurons activated.

Sheep’s blood was found to appeal to the insects, which consumed it with delight. However, attempts to get them interested in saline or sugar water mixtures that had only single components of blood didn’t work, even when the signatures of animals like carbon dioxide or heat (typically used by the parasites as guides towards sources of blood) were added.

To draw them back, the researchers whipped up a blood-like concoction of glucose (sugar), sodium bicarbonate (present in both blood and baking soda), sodium chloride (salt), and adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, a compound that provides energy to cells which is found in all known forms of life. This was a success, and the little parasites flocked to it.

Next, the scientists offered the mosquitoes small tastes of each of the flavor components in the blood mixture to see which neurons reacted. While giving them glucose did not activate any of the neurons associated with the blood-drinking system— perhaps because glucose is also found in nectar—small doses of salt, sodium bicarbonate, and ATP did. Each flavor activated its own set of neurons, similar to how our taste buds react to a specific flavor element.

However, one large cluster of neurons only activated when all four ingredients were present.

According to lead author Veronica Jové, this detection of combinations rather than taste components is a unique adaptation. She explained, “These neurons break the rules of traditional taste coding, thought to be conserved from flies to humans.”

And for the curious, the researchers did sample the ATP mixture they prepared in the lab. They didn’t taste anything. Presumably, the taste of human blood to mosquitoes is akin to the sight of a flower in all its ultra-violet glory to a honey bee. It’s just something we can’t sense or hope to grasp. Though, given the sugar and salt element, perhaps to them it is like the sweet and salty flavor of salted caramels or saltwater taffy.

Not quite, but by increasing our understanding of how mosquitoes work, we can figure out how to keep them off us.

Co-author Dr. Leslie B. Vosshall suggests that, just as we give our pets medicine to keep fleas, ticks, and mosquitoes at bay, this discovery may lead to a drug that makes human blood unappealing to mosquitoes for use by those going into infested areas. If they can’t taste blood, they may not bite in a way that can spread disease.

Mosquitoes are also known to prefer O type blood over all other types. This study may lead to further ones which help explain why. Additionally, because many neurons did not activate at all when the insects fed on blood or its components, further research will have to investigate if they are associated with still other flavors, or if they are related to the act of feeding on blood in different ways.