The new science of optimism and longevity

Being optimistic or pessimistic is not just a psychological trait or interesting topic of conversation; it’s biologically relevant. Indeed, there is mounting evidence that optimism may serve as a powerful tool for preventing disease and promoting healthy aging.

People with an optimistic mindset are associated with various positive health indicators, particularly cardiovascular, but also pulmonary, metabolic, and immunologic. They have a lower incidence of age-related illnesses and reduced mortality levels. Optimism and pessimism are not arbitrary and elusive labels. On the contrary, they are mindsets that can be scientifically measured, placing an individual’s attitude on a spectrum ranging from optimistic to pessimistic. Framing the baseline of each subject in this way, researchers are able to verify the correlation between optimism level and relative health conditions.

In 2019, a review published in JAMA Network Open by Alan Rozanski, a cardiologist at Mount Sinai Morningside hospital in New York City, compared the results of 15 different studies for a total of 229,391 participants. Rozanski’s meta-analysis showed that individuals with higher levels of optimism experience a 35 percent lower risk of cardiovascular events compared to those with lower optimism, as well as a lower mortality rate. Rozanski pointed out that the most optimistic people tend to take better care of themselves, especially by eating healthily, exercising, and not smoking. These behaviors have been found to a much lesser extent in the most pessimistic people, who tend to care less for their own well-being. But the damage produced by pessimism is also biological: The continuous wear and tear caused by elevated stress hormones like cortisol and noradrenaline leads to heightened levels of body inflammation and promotes the onset of disease. Moreover pathological pessimism can lead to depression, considered by the American Heart Association as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Optimists tend to live on average 11 to 15 percent longer than pessimists and have an excellent chance of achieving “exceptional longevity.”

The same correlation has been identified in relation to minor illnesses like the common cold. A 2006 study outlined the personality profiles of 193 healthy volunteers who were inoculated with a common respiratory virus. Subjects who expressed a positive attitude were less likely to develop symptoms of the infection than their counterparts with less positive attitudes. Optimism, then, is one of the most interesting nonbiological factors involved in the mechanisms of longevity because it correlates an individual’s psychological attributes with their physical health. In this sense, it offers us a further strategy to protect our health.

Optimists tend to live longer, as revealed by research led by Lewina Lee at Harvard University analyzing 69,744 women from the NHS and 1,429 men from the aging study of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. The results tell us that optimists tend to live on average 11 to 15 percent longer than pessimists and have an excellent chance of achieving “exceptional longevity” — that is, by definition, an age of over 85 years. These results are not confounded by other factors such as socioeconomic status, general health, social integration, and lifestyle because, according to Lee, optimists are better at reframing an unfavorable situation and responding to it more effectively. They have a more confident attitude toward life and are committed to overcoming obstacles rather than thinking that they can do nothing to change the things that are wrong.

A survey conducted in France in 1998 hypothesized a correlation between the death rate and group events that inspire optimism. On July 12th of that year, at the Saint-Denis stadium, the French national soccer team won the World Cup against Brazil. Data on deaths from cardiovascular events recorded that day show a singular decline compared to the average recorded between July 7th and July 17th, but this effect was limited to the male population, while for women it remained about the same. Although it’s not possible to establish a causal link, this curious coincidence suggests that the massive injection of optimism after the team’s victory may have played a role in the story.

In the optimist’s mind

Starting from the premise that a fundamental part of life is the pursuit of goals, it has been seen that encountering obstacles to achieving these goals can lead to different results depending on the individual’s level of optimism. If the person has a confident and positive attitude, they will try to overcome the obstacle; if they are doubtful that their efforts will succeed, they will tend to let it go, perhaps experiencing frustration from their remaining attachment to this goal, or may become completely disengaged and fail to achieve their goal. Optimism and pessimism posit this mechanism on a larger scale as a mental attitude toward not only a single goal but also the future in general.

Researchers have studied the relationship between these two attitudes and the results obtained during the course of real-life situations. It has been seen that optimists are more likely to complete university studies, not because they are smarter than others, but because they have more motivation and perseverance. And they are able to better manage the simultaneous pursuit of multiple goals — making friends, playing sports, and doing well at school — by optimizing their efforts: showing a greater commitment to priority goals and less commitment to secondary ones.

The optimist seems to invest their self-regulation resources carefully, increasing effort when circumstances are favorable and decreasing effort when they are less favorable, but also by doing more when there is a disadvantage to overcome. In a famous 1990 study by positive psychologist Martin Seligman involving college swimming teams, coaches asked athletes to compete at their best. At the end of the competitions, they were given false results about their performance, increasing their speed by about two seconds, which was low enough to be credible, but still enough for the athletes to be disappointed. After a couple of hours of rest, during which they probably mulled over their bad results in the last race, the swimmers were called to a second race, and the results between the optimists and pessimists were significantly different. The pessimists were on average 1.6 percent slower than during their first performance, while the optimists swam 0.5 percent faster. The interpretation of the experiment was that optimists tend to use failure as a goad to do better, whereas pessimists tend to be discouraged more easily and give up more readily.

Optimism, like a muscle, can be strengthened through positivity and gratitude, says cardiologist Alan Rozanski.

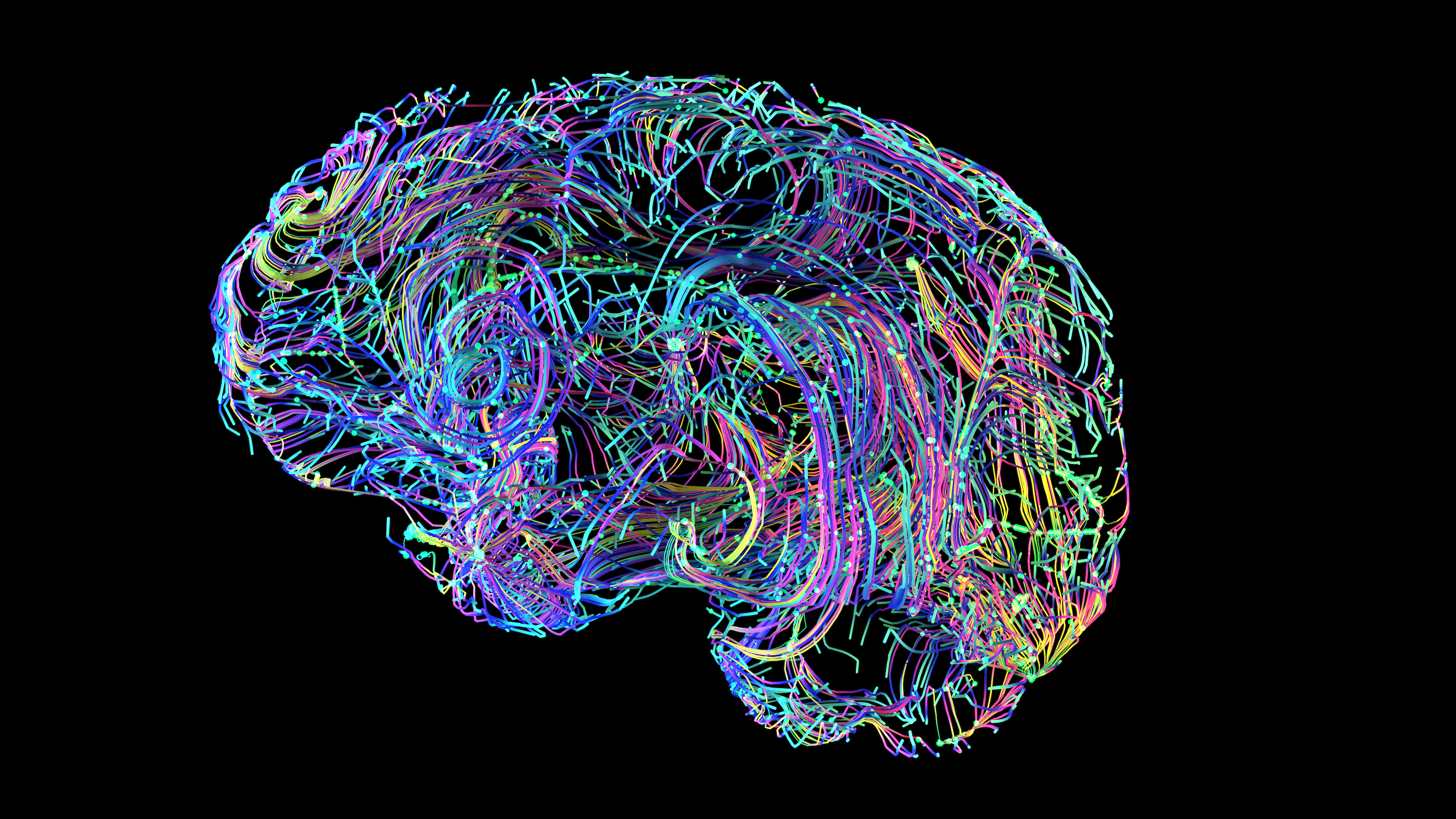

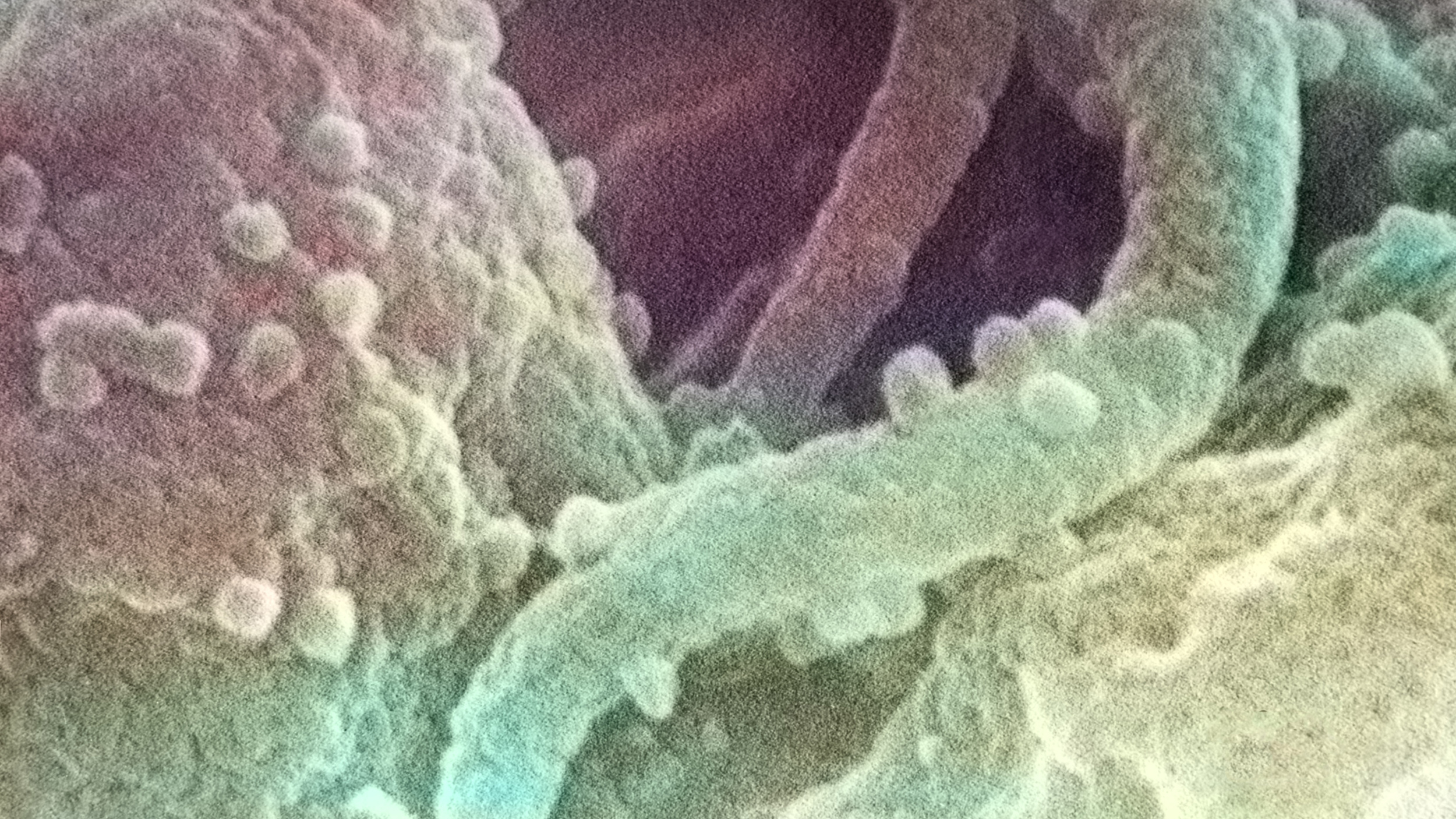

Results of DNA studies also seem to confirm the idea that optimism is an effective tool for slowing down cellular aging, of which telomere shortening is a biomarker. (Telomeres are the protective caps at the end of our chromosomes.) This research is still in progress, but the early results are informative. In 2012, Elizabeth Blackburn, who three years earlier shared a Nobel Prize for her work in discovering the enzyme that replenishes the telomere, and Elissa Epel at the University of California at San Francisco, in collaboration with other institutions, identified a correlation between pessimism and accelerated telomere shortening in a group of postmenopausal women. A pessimistic attitude, they found, may indeed be associated with shorter telomeres. Studies are moving toward larger sample sizes, but it already seems apparent that optimism and pessimism play a significant role in our health as well as in the rate of cellular senescence. More recently, in 2021, Harvard University scientists, in collaboration with Boston University and the Ospedale Maggiore in Milan, Italy, observed the telomeres of 490 elderly men in the Normative Health Study on U.S. veterans. Subjects with strongly pessimistic attitudes were associated with shorter telomeres — a further encouraging finding in the study of those mechanisms that make optimism and pessimism biologically relevant.

Optimism is thought to be genetically determined for only 25 percent of the population. For the rest, it’s the result of our social relationships or deliberate efforts to learn more positive thinking. In an interview with Jane Brody for the New York Times, Rozanski explained that “our way of thinking is habitual, unaware, so the first step is to learn to control ourselves when negative thoughts assail us and commit ourselves to change the way we look at things. We must recognize that our way of thinking is not necessarily the only way of looking at a situation. This thought alone can lower the toxic effect of negativity.” For Rozanski, optimism, like a muscle, can be trained to become stronger through positivity and gratitude, in order to replace an irrational negative thought with a positive and more reasonable one.

While the exact mechanisms remain under investigation, a growing body of research suggests that optimism plays a significant role in promoting both physical and mental well-being. Cultivating a positive outlook, then, can be a powerful tool for fostering resilience, managing stress, and potentially even enhancing longevity. By adopting practices that nurture optimism, we can empower ourselves to navigate life’s challenges with greater strength and live healthier, happier lives.

Cultivating a positive outlook, then, can be a powerful tool for fostering resilience, managing stress, and potentially even enhancing longevity. By adopting practices that nurture optimism, we can empower ourselves to navigate life’s challenges with greater strength and live healthier, happier lives.

Immaculata De Vivo is Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, Professor of Epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, and Co-Director of the Science Program at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute. Her research focuses on how genetic variants interact with the environment to influence susceptibility to hormonal cancers, especially endometrial cancer. She is co-author, with Daniel Lumera, of “The Biology of Kindness,” from which this article is adapted.

This article was originally published on MIT Press Reader.