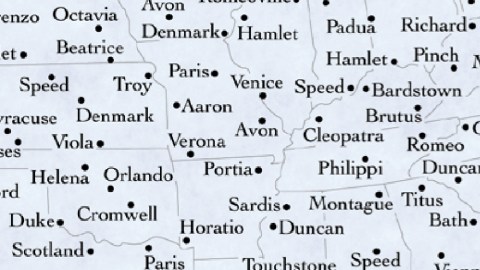

A Map of America’s Shakespeare Towns

Although well received by critics, the debut album by Diesel Park West, a rock band from Leicester (UK), never made it to the top of the charts. It wasn’t for lack of an appealing title: released in 1989, Shakespeare, Alabama conjures up an imaginary town in America’s Deep South, incongruously named after the 17th-century English playwright.

It’s an intriguing juxtaposition. At the time of Shakespeare’s death in 1616, Jamestown, the first English colony in North America, had barely taken hold. And yet the New World had considerable influence on the Bard’s work.

Firstly, in a general sense. In Britain as elsewhere in Europe, the Age of Discovery swept away old certainties, replacing them with the promise of the new, the lure of the exotic. It’s no coincidence Shakespeare named his theatre The Globe.

There are also a few particular references to America – although only a single literal one. In Act III, Scene 2 of the Comedy of Errors, Antipholus of Syracuse and his servant Dromio are playing word-games, comparing the latter’s wife Nell to various lands of the earth (“she is spherical, like a globe; I could find out countries in her”). Dromio compares her buttocks to Ireland, the hard palm of her hand to Scotland, the hotness of her breath to Spain. Antipholus asks:

“Where America, the Indies?”

Dromio answers:

“Oh, sir, upon her nose all o’er embellished with rubies, carbuncles, sapphires, declining their rich aspect to the hot breath of Spain; who sent whole armadoes of caracks to be ballast at her nose”.

The Tempest, considered Shakespeare’s last play, is set on a remote island. Although its exact location is never clarified in the text, the island is generally understood to be somewhere in the New World (1). Less well known is that it was based on true events: in 1609, a fleet of nine English ships heading for Virginia was blown off course and shipwrecked on Bermuda. All hands were thought lost, but passengers and crew eventually managed to repair the ships and complete their journey.

And although Shakespeare never crossed the ocean himself, one actual native-born American has slipped in to his oeuvre.

In 1611, the English captain Edward Harlow kidnapped Epenow and Coneconam from their island of Capawick (now Martha’s Vineyard). They were among the 29 Native Americans brought to England by Harlow, who intended to sell them as slaves. Epenow ended up becoming a ‘wonder’, on constant display in London, and is thought to be the inspiration for the ‘strange Indian’ mentioned by Shakespeare in Henry VIII:

“What should you do, but knock ’em down by the dozens? Is this Moorfields to muster in? or have we some strange Indian with the great tool come to court, the women so besiege us? Bless me, what a fry of fornication is at door! On my Christian conscience, this one christening will beget a thousand; here will be father, godfather, and all together”.

Epenow lived to tell his strange tale to his kinsmen, by the way. He fabricated a story of gold mines on Martha’s Vineyard, and upon arrival escaped the English whose gold fever had returned him home. There is some evidence that Epenow became a sachem (2) among his people, leading the resistance against the English.

Shakespeare never lived to see the English colonies strike root along the entire East Coast of North America, and ever deeper inland. The vast reservoirs of English-speakers in North America would prove useful to England’s literary luminaries of later centuries. They were able to translate their fame on both sides of the Atlantic into extensive tours of the United States. Charles Dickens upon his first visit in 1842 received the full rock star treatment.

On Valentine’s Day, New York’s high society hosted a ball in his honour in the Park Theatre, then the grandest venue in the city. But the star-struck attention soon grew too much for the young novelist: “I can’t drink a glass of water, without having 100 people looking down my throat when I open my mouth to swallow”.

A visit to DC he remembered not for his dinner with president Tyler, but for the copious tobacco-spitting on the streets: “Washington may be called the head-quarters of tobacco-tinctured saliva. The thing itself is an exaggeration of nastiness, which cannot be outdone”, Dickens wrote in his travelogue, American Notes.

“I am disappointed”, Dickens wrote: “This is not the republic of my imagination”. Dickens’s disenchantment was fully reciprocated, by the way. The New York Courier and Enquirer described him as a “low-bred scullion… who for more than half his life has lived in the stews of London”.

The so-called ‘Quarrel with America’ was eventually patched up, and Dickens returned to the U.S. in 1867, to a rapturous reception.

Oscar Wilde’s lecture tour of the U.S. in 1882, originally scheduled to last four months, was so popular that it eventually lasted an entire year. That tour occasioned him to coin the observation that “We (British) have really everything in common with America nowadays except, of course, language”.

And also: “The first thing that struck me on landing in America was that if the Americans are not the most well-dressed people in the world, they are the most comfortably dressed”.

How would Shakespeare have gone down among the beau monde of the East Coast, with the earnest, uncomplicated Midwesterners (Dickens, horrified by their table manners, described them as “so many fellow animals”, who “strip social sacraments of everything but the mere satisfaction of natural cravings”) or, for that matter, in Alabama?

Wherever he would have gone, he probably would have been adulated ad nauseam too. For Americans love their Shakespeare. And have, for centuries. Shakespeare’s works were often among the few prized possessions brought over by the first English colonists who sailed to the New World. Shakespeare plays were staged in America as early as 1750. Travelling the frontier in the 1830s, Alexis de Tocqueville remarked that “there is hardly a pioneer’s hut that does not contain a few odd volumes of Shakespeare”.

In the 19th century, performances of Shakespeare plays were so numerous throughout North America that they drew in shiploads of English actors looking for work and adventure. Mark Twain has Huckleberry Finn float down the Mississippi on a raft with two miscreants who pose as Shakespearean actors, on a tour of the riverbank towns.

Shakespeare was the all-American playwright. Only in the 20th century, when mass media created new frames of cultural reference, did the Bard’s reach narrow from popular to high culture.

Still, Shakespeare’s appeal – or at least the reverence for his talent – remains widespread. Last year, to mark the quadricentennial of his death, the Folger Shakespeare Library sent out copies of the First Folio edition to all 50 states. Printed only 7 years after Shakespeare’s death in no more than 750 copies, the First Folio is the first printed collection of all his plays. Today, 233 copies survive. The Folger owns 82 of them – the world’s largest collection – and normally keeps them behind four sets of safe doors. A total of 18 Folio ventured out in 2016 to make that all-state tour.

A ‘book tour’ four hundred years after the death of the author, that’s fantastic measure of his work’s lasting impact. The First Folio travel schedule around America’s 50 states included the capitals and larger cities of each state. But this itinerary would be way cooler: if the books visited the locations across America that bear the name of characters and places mentioned in Shakespeare.

As this map shows, there are heaps of those, in almost every state – the only Bard-less ones are Maryland and Delaware (and perhaps also Alaska and Hawaii, which are not included).

Granted, some toponymical concordances are likely coincidental, and may not refer to Shakespeare at all. The four Denmarks (in Oregon, Iowa, Wisconsin and Kansas) have probably been named by Danish immigrants rather than by thespian pioneers.

Hamlet, on the other hand, is a more distinguishing name, and more likely to refer to the Prince of Denmark portrayed by Shakespeare in his play of the same name.

Do the four Stratfords and ten Avons dotting the U.S. map refer to Shakespeare’s hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon? Perhaps. How about those Londons in California and Texas? They could well have been named without a thought for the 65 mentions the English capital gets in Shakespeare. The same for Vienna, Georgia, named after the Austrian capital, which is mentioned once in Hamlet, nine times in Measure for Measure. Or Wales, mentioned numerous times as the country, and even more often as the princely title – but still: 32 mentions. So there is a connection, however unintentional.

The rarer the name, the likelier an intentional Shakespeare reference. Especially if it refers to a person rather than a place. Surely the four towns called Romeo (and one Romeoville) refer to the romantic protagonist. Unfortunately, he’ll search in vain for his star-crossed lover on the map: there’s no town called Juliet in America – not anymore. There is a Joliet, Illinois. It was named after the French explorer Louis Jolliet. Strangely, in a corruption of the explorer’s name, the town was actually originally named Juliet until 1845.

There are four Othellos, vying for the attention of just one Desdemona. She’s located in Texas, as is her nemesis, Iago.

The Midwest seems to contain a concentration of exotically-named female characters: Olivia, Miranda, Viola, Octavia, Beatrice.

How weird to consider the blistering desert heat of Ely, Nevada, so different from the freezing winter cold of Ely, Minnesota – but perhaps fitting, as Shakespeare does mention two different bishops of Ely (John Morton, in Richard III; and John Fordham, in Henry V).

Pinch, West Virginia could be named after the conjuring schoolmaster from The Comedy of Errors. And Blunt, South Dakota might refer to Sir Walter Blunt, a chivalrous character in Henry IV, Part I, based on the royal standard bearer, mistaken for the king and killed at the Battle of Shrewsbury (1403).

In fact, neither town is named for their Shakespearean homonym. But what better 21st-century way to honour the Bard than to use these place-names as hyperlink entry points into this work? It is a lot faster and easier than actually reading all those plays.

One name is conspicuously absent from the U.S. map: Shakespeare. No Shakespeare, Alabama or anywhere else. At least not in the United States. There is a Shakespeare, Ontario, though. And there was a Shakespeare, New Mexico. The place (pictured below) is now a ghost town, part of a private ranch, and occasionally open to outside visitors.

Many thanks to David Jouris for providing this map. For similar maps, see his website holdthemustard.com. Picture of Shakespeare, NM found here at Wikimedia Commons.

Strange Maps #786

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

(1) The play contains the phrase ‘Brave New World’, later used by Aldous Huxley as the title for his most famous work.

(2) Sachem or sagamore: a paramount chief among the Algonquians and other Native tribes in the northeastern U.S.